An Englishman Meditates on Thanksgiving and Psalm 114

We had a banquet at Thomas More College in New Hampshire before people dispersed for Thanksgiving. Before the dinner we chose to chant the first 8 verses of Psalm 114 - 'When Isreal came out of Egypt' in order to help us meditate on the meaning of this very American holiday.

When the people of Israel, the subject of the psalm, left Egypt they had two goals. The first was to worship and serve God; and the second was to occupy the Promised Land. On their journey they stopped at Sinai. Here they received their instructions for worship and for a rule of life, before moving on to their final destination. That pause in their journey is significant.

We had a banquet at Thomas More College in New Hampshire before people dispersed for Thanksgiving. Before the dinner we chose to chant the first 8 verses of Psalm 114 - 'When Isreal came out of Egypt' in order to help us meditate on the meaning of this very American holiday.

When the people of Israel, the subject of the psalm, left Egypt they had two goals. The first was to worship and serve God; and the second was to occupy the Promised Land. On their journey they stopped at Sinai. Here they received their instructions for worship and for a rule of life, before moving on to their final destination. That pause in their journey is significant.

‘Sinai, in the period of rest after wandering through the wilderness, is what gives meaning to the taking of the land. Sinai is not a halfway house, a kind of refreshment on the road to what really matters. No, Sinai gives Israel, so to speak, its interior land without which the exterior one would be a cheerless prospect. Israel is constituted as a people through the covenant and the divine law it contains.’(Pope Benedict XVI, The Spirit of the Liturgy, p19)

There are obvious parallels between this and the popular story of Pilgrim Fathers for which Thanksgiving has become a focus. They, like the Isrealites, had worship in mind. They were seeking to institute a sort of religiously based community; and the land they settled in is the land of plenty we now live in. But we would do well to remember also, that it is always a ‘cheerless prospect’ without its Sinai – the interior life that is available to us in its fullest expression through the Church.

There are obvious parallels between this and the popular story of Pilgrim Fathers for which Thanksgiving has become a focus. They, like the Isrealites, had worship in mind. They were seeking to institute a sort of religiously based community; and the land they settled in is the land of plenty we now live in. But we would do well to remember also, that it is always a ‘cheerless prospect’ without its Sinai – the interior life that is available to us in its fullest expression through the Church.

But there is something greater that both point to. All of us in this life are constant pilgrims on that journey in its highest form, the pilgrimage to heaven – that quotation was taken from Pope Benedict XVI’s book on the liturgy. He describes the pilgrimage not seen as as a straight path. Rather, he talks of a constant liturgical dynamic of exitus and reditus – leaving to return home, but each time it is a fresh new home, when we step into the supernatural made present by the Eucharist at the centre of the liturgy. Rather than an enclosed circular motion of repeated worship, it is a helix, in which each cycle takes us further upward. (I explore this idea further in another article, The Path to Heaven is a triple Helix.) Quoting Pope Benedict again, ‘in the Christian view of the world, the many small circles of the lives of individuals are inscribed within one great circle of history as it moves from exitus to reditus’. This is why the liturgy, the formal worship of the Church is described as both ‘source and summit’ of human existence. It is both our supernatural launch pad, a source of grace, and landing field, the heavenly activity is liturgical – the perfect, joyful exchange of love in perpetuity .

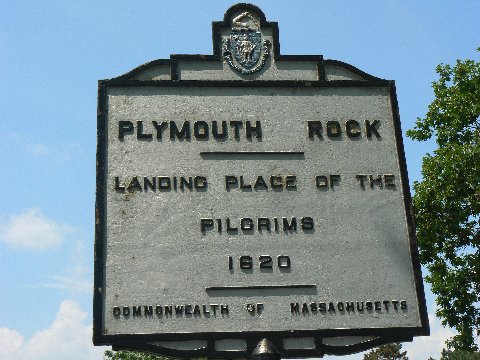

It is interesting that the Pilgrim Fathers’ journey began in Plymouth and ended in a new Plymouth – Plymouth Rock; and similarly ironic that the one thing that would truly have grounded it in an unmoveable rock was supernatural. The Catholic Church that they did not accept. We, because we are aware of this, are in that privileged position of being pilgrims who have that sure and certain guide to our final destination, one that has its foundations in rock, not Plymouth Rock, but the rock of Peter. Then our home, wherever it may be, can be (referring to the psalm) both Judah and Israel, sanctuary and dominion.

It is interesting that the Pilgrim Fathers’ journey began in Plymouth and ended in a new Plymouth – Plymouth Rock; and similarly ironic that the one thing that would truly have grounded it in an unmoveable rock was supernatural. The Catholic Church that they did not accept. We, because we are aware of this, are in that privileged position of being pilgrims who have that sure and certain guide to our final destination, one that has its foundations in rock, not Plymouth Rock, but the rock of Peter. Then our home, wherever it may be, can be (referring to the psalm) both Judah and Israel, sanctuary and dominion.

That is true cause for gratitude on Thanksgiving day.

(As an interesting side note: even the psalm tone that we use to sing Psalm 113 is appropriate to the theme. The ancient tonus peregrinus is always used for this psalm. This translates as 'pilgrim tone' and which was adapted from the pre-Christian Jewish liturgy. We sang it as Anglican chant which adapts the tone to English, and uses four-part harmony.)

Paintings: top, Poussin: Moses String the rock to give water in the wilderness; and above, also Poussin, the Iraelites gathering manna in the wilderness.