We need more people in the world, not less, if we are to solve the world's problems. And we need more gardeners - I am serious here. For the true gardener is the man transformed in Christ who works in the world to raise it up to what it is meant to be.

It is common nowadays for people to think of man as an unnatural animal whose work necessarily destroys the environment. Much of the back to the land movement, I always feel, has a romantic vision of the past and assumes that only a man who lives as he did before industrialization can live in harmony with nature. This pessimistic view of modern man could be seen in various influential figures going back to to Rousseau in 18th century France who hated industrialization and thought that all modern society corrupted ideal man. The ideal for Rousseau was the noble savage who could be conceived, unlike modern man, of living as an intrinsic part of nature as the animals do, rather than in opposition to it.

This may all sound fairly innocuous stuff - a high regard for the environment is good thing, surely? But in fact it is the neo-paganism we see today, that removes man from his a place as the highest part of creation to something separate from it, and lower than it. This false elevation of the rest of creation to something greater than man in the hierarchy of being has serious, deadly consequences. And I do mean deadly.

Man is not only part of nature, he is absolutely necessary to it - the eco-system needs the interaction of man in order to be complete. Through God's grace human activity is the answer to all the environmental problems we have, not the cause. This is the part of Pope Francis's message in his latest encyclical; a part that so many eco-warriors who were enthusiastic about the encyclical seem not to have noticed...or to have ignored. It is possible to have cities, heavy industry, mass production, and forms of capitalism that are creative expressions of the God's plan for the world, and which add to the beauty and the stability of nature. But, we do need a transformation of the culture in order to see a greater realization of this. The formation that I believe will lead to such an evangelization of the culture is derived from a liturgically centered piety and is described in the book the Way of Beauty.

For me, the flower garden is the model of natural beauty in so many ways. First, It symbolizes the true end of the natural world in which its beauty can only be realised through the inspired work of man. It symbolizes what Eden was to become. It is worth noting that Adam was the first gardener and Christ, the new Adam, prayed in the garden during the passion, was buried and resurrected in the garden and after the resurrection was mistaken by Mary Magdalene for the gardener.

Here is a quote from St Augustine from the Office of Readings on the Feast of St Lawrence, August 10th:

'The garden of the Lord, brethren, includes – yes, it truly includes – includes not only the roses of martyrs but also the lilies of virgins, and the ivy of married people, and the violets of widows. There is absolutely no kind of human beings, my dearly beloved, who need to despair of their vocation; Christ suffered for all. It was very truly written about him: who wishes all men to be saved, and to come to the acknowledgement of the truth.'

This may seem a rather innocent little quote about flowers and the things of religion - martyrs and virgins and so on, but in fact reveals so much about the difference in attitudes between one of the Faith, and the modern world. Here's how: we see Rousseau's worldview today in many of the green movements that assume that any influence that man has on the eco-system is bad, because man himself is an unnatural entrant into it, he is not part of it.

Millions of people have been killed as a result of a simple philosophical error. If we believe that civilized man's effect on the environment is necessarily destructive, then the only method of an effective damage limitation is to limit the number of people in the world. The most effective way to do this is to control the population and, because they do not wish to dispense of the pleasure of sex, the solutions offered are contraception and abortion.

The Christian understanding of man and his interaction with the natural world is very different. The first point to make is that both are imperfect. We are fallen and we live in a fallen world. Man is part of nature, and it is certainly true that his activity can be destructive on the environment (just as he commit the gravest crimes against his fellows). However, through God's grace and the proper exercise of free will, he can choose to behave differently. He can work to perfect nature. He has the privilege of participating in the work of God that will eventually lead to the perfection of all things in Christ. Then all man does is in harmony with nature, and with the common good. This is the via pulchritudinis, the Way of Beauty.

There are so many signs in modern culture that reveal this flawed perception of the place of man in relation to his fellows, The changing attitude to the garden is one of these. Even in something that seems so far removed from the issue of abortion, we can see a change which has at its root, in my opinion, the same flaw.

What is the model of natural beauty? For the modern green, neo-pagan it is the wilderness. National parks in the US seek to preserve nature in a way that they perceive as unaffected by man (although this is an impossibility, even the most remote national park is managed wilderness!). I do not say that is a bad thing that some part of nature is preserved, or that the wilderness is not beautiful. Rather, the point is that it is not the pinnacle of nature and it is not the standard of natural beauty. When man works harmoniously with the environment, then he makes something more beautiful. Beautifully and harmoniously farmed land takes the breath away - as we might see in the countryside of France, Spain, England and Italy for example, places of which I am familiar. This the sort of landscape in which Wordsworth saw his host of wild golden daffodils.

Higher still is the garden that is cultivated for beauty alone. A garden is a symbol of the Church. Each part, each plant is in harmony with every other just as every person who is unique has his place in God's plan, as St Augustine points out in the quote given above. Gardens will have their place in the New Jerusalem. We know this because the description of the City of God in the Book of Revelation contains gardens.

The activity of gardening for beauty is a symbolic participation in the completion of the work of God in the world for it raises creation up to what it ought to be, through God's grace. The garden itself is a sign to all others of the fact that all of creation is to be transfigured supernaturally. The act of gardening is both reflective of and points to, therefore our participation in the Sacred Liturgy by which we are transfigured and by which we participate in the work of God. Gardening for beauty is an act of love that is formed by our greatest act of love, the worship of God in the Sacred Liturgy. It can be likened to the action of Mary with our Lord, anointing his feet; and contrasted with the cultivation of the land in order to create produce to eat, which can be likened to an action of Martha. Both are good, but Mary's is the highest.

Pius X likens the activity of gardening to that of singing the Psalms in the liturgy: 'The psalms have also a wonderful power to awaken in our hearts the desire for every virtue. Athanasius says: Though all Scripture, both old and new, is divinely inspired and has its use in teaching, as we read in Scripture itself, yet the Book of Psalms, like a garden enclosing the fruits of all the other books, produces its fruits in song, and in the process of singing brings forth its own special fruits to take their place beside them.' (This is taken from the Office of Readings for August 21st, the Feast of Pius X).

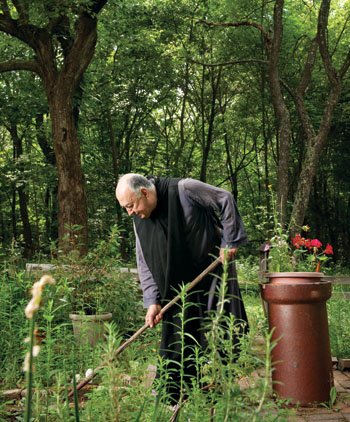

The gardener is the symbol of the transfigured man who works in harmony with nature to create something greater for the delight and good of man and for the greater glory of God. The highest aspect of what he does is the beauty that he creates. This beauty has the noblest utility, one that takes into account our supernatural end for it prepares the souls of men to be receptive to the love of God in the Sacred Liturgy.

Leo XIII said in his encyclical Rerum Novarum, that man should be encouraged to cultivate the land. I have heard this cited by some Catholics in the back-to-land movement so as to imply that it is almost a moral obligation to have chickens in your backyard, to keep bees or to grow vegetables. I say, if you enjoy those things then go ahead and do it, but I feel no such obligation myself. I for one have little interest. I am perfectly happy to buy a ready-cooked chicken for under $5, jars of honey and vegetables and fruit from all over the world year round from the local supermarket.

However, what is not so often remarked upon is that Leo says that in cultivating the land, man will, 'learn to love the very soil that yields in response to the labor of their hands, not only food to eat, but an abundance of good things for themselves and those that are dear to them [my emphasis].' I suggest we learn to love the soil especially when it yields beauty; and when it is through our own efforts that it does so. There is no need for three acres and a cow for this to happen. For some this might mean the tiniest patch of land around your house, or if you don't have that a window box; or if you can't do that some well tended plant pots inside your high-rise apartment. We don't need to head for the outback or escape from the cities or the suburbs. However, modest our resources, this can be an act for love for the glory of God and for the enjoyment of those dear to us. When this is done it can have the profoundest effect on a neighborhood, as we can read by this example in Boston.

When the garden is enjoyed for its beauty it can be a contemplation by which we are passively open to the reception of Beauty itself. This is why it is a good thing to approach a church through a cloister that looks onto a 'garden enclosed'. The garden enclosed from the Song of Songs, is seen by the Church Fathers as a reference to Mary, the Mother of God, by whom we approach the Son.

It is no accident, I suggest that today even botanical gardens and public gardens which used to be formally laid out, are now being turned into 'natural' or wild gardens, in which the aim is, it seems, is to reduce it's beauty (although they would probably argue that it is the opposite) and resemble something that is like the wilderness - base nature, unaffected by the inspired work of man. Even the lowest form of nature is beautiful, I don't deny it. But that is not a garden. When we make the standard of natural beauty its lowest form, then such a garden is a symbol of the banishing of man from the world altogether, of Unnatural Man so to speak, and an emblem of the culture of death. The next logical step after the misguided glorification of Unnatural Man is to strive for the absence of man altogether and this is what we see through our abortion clinics.

Who would have thought that the simple cultivation of ivy, roses, lilies and violets could say so much! I would consider it the greatest compliment if someone would mistake me for the gardener.

Cristo appare a Maria Maddalena (Christ appearing to Mary Magdalene)" by Pietro da Cortona from Wiki commons

I have written about this painting in more detail here.

This access will also, I believe raise people's wonder at the beauty of cultivated land (whether ornamental garden or agricultural) and so perhaps help to offset the neopaganism that gives rise ultimately to the culture of death. When the only country landscape available to man is wilderness, and all else he sees is modern suburbia or a cityscape, then it reinforces the idea that the standard of beauty is that land which is untouched by man, that is wilderness. This in turn reinforces the idea that man's influence on nature is always detrimental and the natural extension of this idea is profound evil: the most effective way to restrict man's bad influence on nature, so the logic runs, is to restrict his activity through population control, which means contraception, abortion and euthanasia.

This access will also, I believe raise people's wonder at the beauty of cultivated land (whether ornamental garden or agricultural) and so perhaps help to offset the neopaganism that gives rise ultimately to the culture of death. When the only country landscape available to man is wilderness, and all else he sees is modern suburbia or a cityscape, then it reinforces the idea that the standard of beauty is that land which is untouched by man, that is wilderness. This in turn reinforces the idea that man's influence on nature is always detrimental and the natural extension of this idea is profound evil: the most effective way to restrict man's bad influence on nature, so the logic runs, is to restrict his activity through population control, which means contraception, abortion and euthanasia.

City parks and gardens derive their beauty as much from the public art as they do from the plants grown. Public art, of course has a greater impact also in those areas where there is no cultivation and Trafalgar Square in London is made by the Lions and Nelson's column as well as the beauty of the buildings on it. There is a plinth on in the corner of Trafalgar Square and that is always given to a piece of contemporary art which changes regularly. The latest fiasco to occupy this spot is time a giant purple cockerel that looks as though its made out of resin. What an absurdity! The scale of a piece of art speaks of its importance - the huge size of this, and its garish unnatural colour make it dominate the whole square, clashing with the otherwise harmonious arrangement of the other works in the square and working contrary to the natural hierarchy, in which cockerels come below man.

City parks and gardens derive their beauty as much from the public art as they do from the plants grown. Public art, of course has a greater impact also in those areas where there is no cultivation and Trafalgar Square in London is made by the Lions and Nelson's column as well as the beauty of the buildings on it. There is a plinth on in the corner of Trafalgar Square and that is always given to a piece of contemporary art which changes regularly. The latest fiasco to occupy this spot is time a giant purple cockerel that looks as though its made out of resin. What an absurdity! The scale of a piece of art speaks of its importance - the huge size of this, and its garish unnatural colour make it dominate the whole square, clashing with the otherwise harmonious arrangement of the other works in the square and working contrary to the natural hierarchy, in which cockerels come below man.