What did John Henry Newman mean when he wrote in his essay “The Mission of St. Benedict” that the discriminating badge of the Benedictines is poetry? By saying that the Benedictine charism was poetry, Newman does not mean that Benedictines spent all day writing poems. St. Benedict did not found a religious order aimed purely at mystical knowledge—experiences of God that remain in the soul, and tend towards silence. In contrast to monks who fled the world to encounter God in solitude, St. Benedict’s Rule was written to guide communities in living elemental aspects of Christianity—such as shared meals, shared prayer, and shared work. Life in common is the Benedictine monastic path toward God.

As the philosopher Jacques Maritain writes, “poetic experience is concerned with the created world and the enigmatic and innumerable relations of beings with each other.”[1] Poetic knowledge expresses itself in work through a dynamic process: “Poetic experience is from the very start oriented toward expression, and terminates in a word uttered, or a work produced; while mystical experience tends towards silence.”[2] Poetic knowledge is therefore communication between the soul and the world, since:

The soul is known in the experience of the world and the world is known in the experience of the soul . . . In poetic intuition objective reality and subjectivity, the world and the whole of the soul, coexist inseparably. At that moment sense and sensation are brought back to the heart, blood to the spirit, passion to intuition. And through the vital and nonconceptual actuation of the intellect all the powers of the soul are also actuated in their roots.[3]

In Newman’s words, the gift of the Benedictines is a way of being in the world that “lets each work, each occurrence stand by itself—which acts towards each as it comes before it, without a thought of anything else.”[4] Newman even calls this approach to life a “mortification of reason,”[5] but that is not because St. Benedict and his many followers devalue scientific or conceptual knowledge reached through reason.

Rather, at times, our tendency to analyze, measure, and manipulate needs to be forgone in order to return to a childlike, simple state of perceiving reality that opens up to a sacramental way of living—seeing in visible things the invisible grace of God. The Benedictine vision reminds us that to see the totality of things and to live a contemplative life in the ordinary work of manual labor and repetitive daily routines requires an attentiveness to the present moment and commitment to particular people and places. Being present to all of reality—without having to always conceptualize our experience or analyze things scientifically—is a way of encountering God intimately and simply, like a child who wonders at the beauty of each flower and rejoices at every bird in the sky.

By calling the Benedictine way a simple, almost childlike way of living, by no means was Newman discarding the importance of Benedictine contributions to science (in particular through agriculture), as well as letters (for example, St. Bede the Venerable, the English historian and Gospel translator). Indeed, the Benedictines have plenty of cause to boast of their great saints who exemplified holiness, such as Saint Anselm or Saint Hildegard, both of whom are Doctors of the Church.

Newman contrasts the Benedictine gift of poetic living to the noble, but distinct, mission of other orders in the Church that sought to be apologists for the faith, teachers in the pulpit, professors in the chairs of universities, and rulers of the Church. The Benedictine way counteracts the miseries of life with beauty. Benedictines model how to have an open ear listening to God and a heart ready to receive the truth.

Newman’s summary of the Benedictine way of life from his essay on the Benedictine Schools summarizes beautifully the particular gifts of the Benedictines: simplicity, commitment to place, routine, hospitality, and seeing the totality of reality. Benedictines see the sparkling of divine creation in every living organism, from the sky that covers all of creation to the microbes of the soil. As Newman writes:

The one object, immediate as well as ultimate, of Benedictine life, as history presents it to us, was to live in purity and to die in peace. The monk proposed to himself no great or systematic work, beyond that of saving his soul. What he did more than this was the accident of the hour, spontaneous acts of piety, the sparks of mercy or beneficence, struck off in the heat, as it were, of his solemn religious toil, and done and over almost as soon as they began to be. If today he cut down a tree, or relieved the famishing, or visited the sick, or taught the ignorant, or transcribed a page of Scripture, this was a good in itself, though nothing was added to it tomorrow. He cared little for knowledge, even theological, or for success, even though it was religious.

He continues thus:

It is the character of such a man to be contented, resigned, patient, and incurious; to create or originate nothing; to live by tradition. He does not analyze, he marvels; his intellect attempts no comprehension of this multiform world, but on the contrary, it is hemmed in, and shut up within it. It recognizes but one cause in nature and in human affairs, and that is the First and Supreme; and why things happen day by day in this way, and not in that, it refers immediately to His will. It loves the country, because it is His work.[6]

What kind of education did St. Benedict himself envision? In reflecting on the schools started by St. Benedict, Newman points out that St. Benedict’s schools were focused on the young. What is today known as high school or higher education hardly existed in the tumultuous times in which St. Benedict lived. Academies of higher learning were for the elite. The Benedictine way of life and Benedictine education was for the ordinary Christian, the person in adult life who would engage in manual labor.

In the twenty-first century, even pre-kindergarten instructing has often shifted to college readiness, as if what matters to toddlers are the skills that will help gain admission to a college where the nearly exclusive focus on scientific and conceptual mode of living shuts out the poetic way of living that allows us to integrate our intellect with our soul. By contrast, St. Benedict followed a kind of liberal arts model of education (teaching the subjects of the trivium and quadrivium) for the young, including the Greek and Roman classics and instruction in Scripture in his grammar schools for the young. Certainly the Benedictine poetic way of living and educating—a simple, joyful emphasis on teaching languages, learning about nature, and studying the history and stories of great civilizations of the past—mingled easily with the desire to nurture a child’s wonder at the marvels of nature or history and a child’s eager intuition to find symbolic meaning in all things.

All levels of education would benefit from nurturing the creative intuition that is the engine and fruit of poetic knowledge. The importance of the Benedictine charism is evident in its power to elevate the being mode of life and shut down (or at least slow) the analytical mode of life aimed at investigating means and ends, predicting outcomes, or examining premises and conclusions. Not educating the inner core of our soul from which all other capacities emanate—including our reason—leads (and has led) to dissonance, dispersion, and the fragmentation that results from a lack of direction for our drives, passions and instincts. Pondering the Benedictine charism of poetry can positively shape the Church, schools, and culture today in (at least) three concrete ways.

First, reading and writing poems is one way to capture the complexity of objective reality and to express our own emotions—which confronts the challenge in today’s culture in that many people suffer from a crisis of attention and a lack of imagination. Catholic poet and former director of the National Endowment of the Arts Dana Gioia has argued that the study of poems and the writing of poetry needs to be recovered.[7] Writing and memorizing poetry used to be an activity of common people, not academics in universities. Studying great works of literature like the Divine Comedy matter because stories shape our imagination and guide us when making important decisions about our lives. Great literature opens our hearts to respond to the attraction of the good. Literature lights the fire of our desire for a blessed life.

Second, reviving poetic knowledge is crucial to the advancement of scientific knowledge. Marveling at the beauty of the world—whether that be the beauty of soil or the beauty of the many mathematical calculations that make a building structurally sound—is not secondary to technological advancement, but primary. As Catholic professor of mathematics and physics Carlo Lancellotti has argued, scientific advancement is driven not primarily by technological innovation but by the creative intellect that seeks to know why things work, not just how they work. Seeking to understand why things work as they do, as Lancellotti puts it, “the ultimate motivation that has led to the triumphs of modern science is essential aesthetic.” The ability to marvel at the world needs to be cultivated because it is the seed of the sustained human effort to know why things work the way they do. Math, science, and engineering education that never takes students out of the controlled environment of the laboratory too often squashes the very human creativity that not only drives new scientific discoveries but also guides their application towards ends that promote human flourishing.[8]

Third, reviving poetic knowledge is crucial to liturgical renewal because poetic ways of everyday living are essential for educating the imagination and intuition as they are engaged in the liturgy. Timothy O’Malley, director of the Center for Liturgy at the University of Notre Dame, has arguedthat within the Catholic Church, many do not appreciate poetic forms of knowledge, not even in the liturgy. Is it surprising, then, that the failure to educate our aesthetic sensibilities leads to poorly done liturgy that is sense-numbing and unimaginative? Too many parishioners are unable to sufficiently focus their attention to enter into the contemplative space of beautiful liturgy. Aesthetic education in art, literature, and science can enliven liturgical experiences of the faithful and motivate clergy to celebrate the Mass with beauty. Liturgy well done is itself a form of aesthetic education.

A poetic, sacramental way of living and educating the young can never fully be conceptualized. It has to be lived and to be experienced in order to be known more fully. In the chapter on humility from his Rule, St. Benedict discusses the image of the ladder (in Latin, scala). Benedict instructs readers that:

If we wish to reach the very highest point of humility and to arrive speedily at that heavenly exaltation to which ascent is made through the humility of this present life, we must by our ascending actions erect the ladder Jacob saw in his dream, on which Angels appeared to him descending and ascending. By that descent and ascent we must surely understand nothing else than this, that we descend by self-exaltation and ascend by humility. And the ladder thus set up is our life in the world, which the Lord raises up to heaven if our heart is humbled. For we call our body and soul the sides of the ladder, and into these sides our divine vocation has inserted the different steps of humility and discipline we must climb.

This image of the ladder gives the name for the Scala Foundation, a non-profit initiative that aims to revive classical liberal arts education, of which I am the founder. Scala aims to link educational philosophy to practices and that educate the whole person, including integrating the search for truth with experiences of beauty.

Through Scala, I have led student groups to Benedictine monasteries such as the Abbey of Regina Laudis and Portsmouth Abbey in the United States, as well as Ampleforth Abbey in the United Kingdom. Each trip combined time dedicated to forming the mind with time dedicated to immersing ourselves in the Benedictine routine of the liturgy of the hours, shared meals, manual labor, and playing games. Reading Newman’s Idea of a University, Jacques Maritain’s Education at the Crossroads, and Luigi Giussani’s Risk of Education while at a Benedictine monastery allowed us to immediately put into practice the ideas of some of the greatest Catholic thinkers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. We deepened our knowledge of the texts we read because we lived what we were reading.

These trips afforded us a slice of the original beatific vision because we lived an integrated life where everything we do, think, and feel comes from the soul, the place of the direct encounter with God, and emanates out into a sacramental way of living every moment of the day. Whether we were in the classroom, the strawberry field, the chapel, or the dining hall, the Benedictine communities created a sense of harmony with nature that produced a deep inner resonance so deeply desired by today’s students and their instructors. The unity of all activity, interior and exterior, generates peace and gently guides students into a state of productive leisure where all of our being and doing points towards the sacred.

Anyone who has tried to follow the Benedictine routine knows that the lifestyle is too demanding and the education too holistic to be conceived of as a mystical floating above earthly realities or a retreat from the world’s conflicts. The simple, daily routines of manual labor, prayer, study, and a shared way of life, along with a spirit of attention to the divine in the liturgy of the hours and lectio divina of both Scripture and nature captivates students’ hearts and prunes their minds. Poetic knowledge can guide scientific and conceptual forms of reason to be used more in harmony with our souls.

As Pope Benedict XVI notes in his address Quaerere Deum, the Benedictines transformed European culture slowly, but not through a political strategy. Little wonder that he chose the name of Benedict for his papacy, as he argues that the Benedictine monastic tradition that reveres the word of God and all of creation is both “what gave Europe’s culture its foundation—the search for God and the readiness to listen to him—[and] remains today the basis of any genuine culture.”[9] The Benedictine influence on society is the result of its producing resonance and harmony in the soul which in turn sow the seeds of life-giving culture. In the past, the Benedictine commitment to preserving ideas of the past, living in community, and preserving the land to be bountiful brought order out of chaos. It surely can do so again.

The curricular fragmentation in schools at all levels and the interior dissonance of students are not unrelated. As a result, the Benedictine charism is being studied, experienced, and applied by educators who, like myself, will not become monks or nuns, but are looking for a way to purify today’s educational systems. Educators need positive examples that can be drawn from the Benedictines in order to build on the good of today’s culture and of current school structure. It is important to critique the obsessively achievement-oriented, narrowly pragmatic, and ultimately soul-draining forms of education, while also being inspired by models that help educators swim against the stream where an understanding of the Benedictine (and Catholic) vision is missing but its influence is nevertheless felt.

Benedictine communities are an embodiment of a tradition that has preserved a living expression of a unified, simple, yet also glorious and joyful way of Christian life and education. Monks and nuns working the land and running schools who welcome student groups for agricultural work, retreats and seminars can be hospitable guides to people from all faith backgrounds and types of schools. Benedictines offer an ancient tradition of daily living and a method of education that is also ever new and capable of bringing interior and external order to our culture and our schools.

[1] Jacques Maritain, Creative Intuition in Art and Poetry (Providence, RI: Cluny Media, 2018), 216.

[2] Ibid., 216.

[3] Ibid., 113.

[4] John Henry Newman, “The Mission of Saint Benedict,” in A Benedictine Education: The Mission of Saint Benedict & The Benedictine Schools, ed. Christopher Fisher (Providence, RI: Cluny Media, 2020), 11.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., 74.

[7]See Dana Gioia, The Catholic Writer Today: And Other Essays (Wiseblood Books, 2019).

[8]Margarita A. Mooney, “Engineering, Beauty and a Longing for the Infinite,” Scientific American, October 22, 2019.

[9]Pope Benedict XVI, “Quaerere Deum,” in A Reason Open to God: On Universities, Education and Culture, ed. Steven J. Brown (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2013), p. 236.

This article originally published online at Church Life Journal and is adapted from the Introduction to A Benedictine Education, a collection of essays by St. John Henry Newman, edited by Christopher Fisher, with an interpretative essay by Abbot Thomas Frerking, O.S.B. The volume is a Cluny Media title, published in partnership with the Portsmouth Institute.

Scripture, part of the foundation of joy (part one, part two tomorrow)

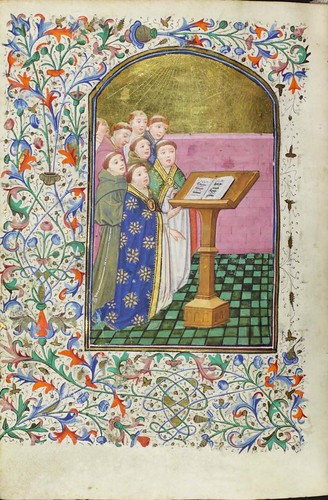

Scripture, part of the foundation of joy (part one, part two tomorrow) Here is St Bonaventure (whose picture is shown) from the Office of Readings of Monday Week 5 of the year:

Here is St Bonaventure (whose picture is shown) from the Office of Readings of Monday Week 5 of the year: