God gives us all a role to fulfill, it is for us to choose whether or not we do so. our time to make that choice grows shorter.

The Poet and the Hound of Heaven

The Cave You Fear To Enter

The Artist's Spiritual Journey

Men's Monastic Experience Weekend

Monastic Experience Weekend, May 31: St Mary's Benedictine Monastery, Petersham

Our Time To Choose

The Artists and the Church - John Paul II

Pope Saint John Paul II perhaps understood the sensibility of artists better than most pontiffs. He was, after all, a poet, playwright, and actor himself. His Letter to Artists, written in 1999, deserves special attention among those struggling to find a way to reconcile being an artist with being Christian.

The Artists and the Church - Paul VI

The Call of the Artist

The Artist Teaches Through His Art

Discerning Vocation: How I Came to be Doing What I Want to Do

The Artist's Fight

The Artist As Prophet

We tend to think of a prophet as one who predicts the future, but that is not at all the ancient understanding of the word. The word "prophet" means speaker, or one who speaks. In Christian use, a prophet is one who has a special connection to God and speaks on God's behalf.

By virtue of our Baptism we are invested in the threefold office of Christ, priest, prophet, and king. The degree to which we fulfill each of these offices will depend on our individual gifts and calling. We are all called to be prophets, as well as priests and kings, to the degree our gifts allow us.

A One-Minute Daily Spiritual Exercise for Cultivating Faith, Joy, Gratitude, an Ability to Apprehend Beauty...and It Might Even Be a Treatment for ADHD!

Try it for 30 days, and if you don't like it, we'll return you misery with interest!

Here's a quick and simple exercise I have been doing daily for nearly 30 years and it has brought such spectacularly positive results in my life that have accumulated steadily and incrementally ever since I started.

Every day, I jot down on a scrap of paper a 'gratitude list'.

The gratitude list is a list of good and beautiful things that have been given to me today for which I offer thanks to God. I put down the 'essentials' of life that are true for today, for example, I am alive, I have a bed to sleep in today, I have somewhere to live, food for today, clothes to wear and so on. I then put down all the little events specific to that day that go beyond what is necessary for life, you might call these 'luxuries', for example, sunshine on this January day (sorry New Hampshire), a kind word here, the relationships with others that I have and so on.

Actually writing the list is important - it forces me to crystallize the thought in my mind that much more concretely and makes the exercise more powerful. So nice thoughts in the shower, or on my morning walk don't count. It's not that there's anything wrong with that but it doesn't work as well for this exercise. I reach for pen and paper.

Also, I don't wait to feel grateful before I put them down - I write down what I ought to feel grateful for! The idea is that this exercise changes how we feel, and we grow in gratitude over time even if we don't start out that way. So right now I am grateful for a huge cup of steaming coffee! Fantastic!

Then I go further, I write down the bad things happening in my day and thank God for those too.

It may sound perverse, but this is powerful for turning around my attitude to what is happening to me. I believe that all that is good comes from God and that once we hand ourselves over to his protection and care he will look after us. While it is undeniable that there is evil and suffering in the world, these things to do not come from God, for a God that is all good cannot be the creator of something bad. Rather, he permits bad things to occur in order that a greater good can come out of them.

For this reason, I make a point of putting down negatives and disappointments of the day on the gratitude list too, knowing that a greater good must be coming out of it (even if I can’t see it yet). The realization of this helps me to deal with adversity with dignity and when I praise God for them (as St Peter tells us to do in one of his first letters) it helps me actually to feel good about them.

I look to the example of the saints for inspiration, including that of St Peter himself, who dealt with greater suffering than I have ever had and praised God for it. So I can say to myself, okay, it's pretty bad that I missed my train...but I'm not being crucified or stoned to death as St Stephen was. The account of St Stephen in Acts shows us that hope in God transcends all suffering if we can follow the promptings of God's grace. This exercise helps me to move that ideal incrementally.

Furthermore developing the habit of seeing minor irritations in this way is invaluable when more serious things happen to me. I have not had to face stoning or torture in a concentration camp, but in 30 years I have experienced some genuinely bad things - arising from the malice of others, my own selfishness or foolishness - or just plain bad luck. Having practised an attitude of faith and hope that transcends the small reversals on the regular basis, it is easier to see that what is true for the little things is just as true for serious disappointment and suffering. It has to be so. After all, if it's not true for the big things too, then it's not true at all. This exercise helps me to feel what I know intellectually to be true.

People can go on the gratitude list too: those we love...AND those we don't! If I have a resentment against a person, I put the person I don't like down and pray for that person too. Once written down I then pray repeatedly until I feel better, 'Please give X%#F&! everything I would wish for myself'. Sometimes it is through gritted teeth I can tell you! The more I dislike the person, the better things I ask for them. It might even be...(take your pick)...

Also, this is an exercise that can help us to enjoy what is beautiful. I am not by nature given to gratitude and can tend to take good and beautiful things for granted very quickly. So in my day, I especially look for beautiful things in the context of what might otherwise seem bad. I work on the principle that if I start to notice the little things, then it develops my appreciation for the grand vista too. One of the attributes of beauty is due proportion. If I develop the habit of noticing the parts and the details, then it helps me to see the good of the whole too. In other words, it helps me both to analyse and synthesize. These are skills that contribute to my ability to apprehend beauty - to see the part in relation to the whole, and the whole in relation to others. I suggest that every creative artist should develop this habit as part of his formation!

The dynamic of analysis and synthesis can be applied to time as well as space. In every moment there is something good happening, even if my general response to what is going on is initially bad. This how I can stop a few hurtful words before lunch influencing my sense that I am 'having a bad day', and instead allow the good to characterize the day. This is not only a better attitude to have, it is in accord with what is true. We know the day is good, objectively, because it is made by God and it is a gift given to all of us. This exercise allows us to feel what we know to be true in this regard. This is a similar frame of mind to what modern new-age therapy calls 'mindfulness' except, I would say, this runs deeper and truer. And it has a longer and broader pedigree coming out of traditional Christian mysticism.

So abandon this...

and focus more on being like the dog who waits expectantly for the crumbs from his Master's table, or alert to every murmur of his master's voice...

And this is why I say it could be an exercise that develops better concentration and attention to detail. I have wondered at times if, judged by my natural levels of concentration, I could be diagnosed with low-level ADHD. Certainly, I struggle more than I would like to concentrate on anything I'm not hugely interested in and would always rather listen to the talking book while driving the car than read it just because I can't sit still. I don't read fiction and haven't read a novel in years apart from easy-read detective stories. I like getting news in 5-minute podcasts and can hardly focus on a newspaper. I don't know how this compares with the norm for the population (and I have often wondered if it's down to all the coffee I drink) but regardless, this exercise does help to at least to get some things done and to enjoy the process as well.

It's not always a bad thing. I like squirrels and I'd rather be looking at a squirrel than contemplating my poor powers of concentration anyway. Joking aside, I know there are many whose lives really are made extremely difficult by a chronic inability to stay focused. Even so, I wonder though if a daily meditation of this type might help even those who are genuinely ADHD? It can't do any harm. And it is a task that needs very little attention time in itself. It takes me a minute or two at most to do this. The effect is cumulative - I was told initially to try it for 30 days and see how I felt at the end of that time.

So, I encourage to try it yourself and see how it goes. Remember, the Divine is in the detail!

Some of you may wonder what prompted my starting this habit nearly 30 years ago? The answer is that I met someone, an elderly man called David, who told me something that shook me when I heard it - misery is optional. When I heard it, my first reaction was to be certain he was wrong. I was certain because I was miserable, and if he was right, I would have to admit some terrible truths. First of these was that David knew more about how to live happily than I did; the second was that I was responsible for my unhappiness. My pride was such that I couldn't possibly admit either of these things easily.

Prior to meeting David, if I met a happy person the only way I could reconcile my misery and intellectual pride with their joy was to assume they were deluded or foolish, and probably both. Happiness, I had always thought, is the preserve of the stupid and superficial thinkers. When you are deep thinking and intelligent like me then you understand the profound truth that life is miserable. But David opened my mind by presenting me with a version of Pascal's wager (although I didn't realise that this is what he was doing), he challenged me to try it.

I had met David through a mutual friend who had invited me to coffee on the King's Road, in Chelsea when I was living in London. (It was a restaurant called Picasso's - I don't know if it's still around.) David was talking to my friend when he said this provocative statement, but when I heard him say it, I felt I had to intervene. In my unhappiness, I was one of those people who was so irritated and envious of happy people that I considered it a service to explain to them how deluded they were. So I interrupted and began to explain to him that although he might think he was happy, in fact, he was really unhappy (absurd as this sounds). David let me speak for a while, as I tried to reconcile the irreconcilable, and then cheerily stopped me: 'Please yourself, lad,' he said. 'But why don't you try the theory out?'

My friend then chimed in and said he had been doing a simple program of daily prayer and meditation that David had suggested to him and this had changed his outlook dramatically and encourage me to do the same. It was this personal recommendation from someone I liked that made me pause.

David told me he would happily show me these things too if I was interested. 'Try it for 30 days, do everything I suggest, and if you don't like it we'll return your misery with interest!' he said. The process that he gave me was called the Vision for You process. It was a daily routine of prayer, meditation, contemplative prayer and good works that are both simple and practical and involved about 10 minutes a day, plus a weekly voluntary commitment of service anywhere where I could be of use. I decided that it couldn't do any harm to try and he wasn't asking for money, so I thought I'd give it a go.

Something that persuaded me was that I had noticed a change in the positive in my friend, I thought, in recent weeks. He had started to become irritatingly cheerful and couldn't be.

The gratitude list is just one of the simple spiritual exercises he gave me and I would say that without a doubt it works. I can't prove it, of course, but I am convinced enough by it to have kept going with it daily for a long time. Another one of the exercises he gave me was to get on my knees in prayer every day and ask God to look after me so that I could give glory to Him and be of service to my fellows. As David said to me all those years ago put it, the gratitude list is written proof that when you asked God to look after you today, he answered your prayers.

Not that I saw it that way initially. David wrote my first gratitude list for me because I didn't really feel grateful for anything. So he took pen and paper and asked me, you are alive today aren't you? He waited for me to say, 'Yes' and then wrote it down. 'And you have clothes to wear?' Again he waited for me to agree to each item so that I confirmed that what was going down was true. 'And food to eat, for today at least?'...and a roof over my head? And a bed to sleep in? When I had agreed to each item as being true for me, he paused and said, 'You are now ahead of billions of people in the world who don't know where their next meal is coming from. Here is the evidence that the day is good. You have no good reason for complaint.'

David told me that this whole process, the Vision for You, would do more than raise my baseline of misery. It would give me a life 'beyond my wildest dreams', engender a deeper faith in God and help me to discern and realise my personal vocation. Some of you may remember a post from a long time ago in which I described how I became an artist. It is here - Discerning My Vocation as an Artist. David is the man I was talking about in this earlier article. He showed me how to be doing what I do now! It is also the process that converted me to Catholicism, and David was my sponsor when I was received into the Church in 1993 nearly five years later. Sadly he died of a heart attack in 1998 - nearly 20 years ago now. I would have loved him to see just how much this process, which I still practice to this day, continues to give me so much in my life and in the lives of people that I have passed this on to over this period. There are dozens.

I don't have the space to describe the full process here - I have a book manuscript ready for publishing which is over 200 pages long and which describes the whole story in detail. Once I had the initial daily routine as a habit and I decided that it was working, David introduced me to a series of deeper structured reflections and it was at these that included the discernment process. All in all, it took several months. It was work, but it was worth it!

David said that he would give freely of his time and consideration, but only on condition that if I benefited from it, I would be prepared to pass it on, in turn, to any others who wanted what was on offer. This is why I am happy to help anyone who is interested in following this process today if they are serious about doing it. If you have questions about it, do feel free to contact me, but in the meantime here is a document which contains a summary of the process, the spiritual exercises, the daily routine and the discernment process.

Master of Sacred Arts at www.Pontifex.University - a cultural, intellectual and spiritual formation in beauty and creativity for artists, patrons of the arts, and anyone who wants to contribute creatively to the establishment of a culture of beauty today.

Institute Verbo Encarnato (IVE) - the Institute of the Incarnate Word

An order that embodies the principles of joyful evangelization in accordance in the spirit of Pope St John Paul the Great and Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI.

This past week, I was lucky enough to be invited to give a couple of talks on art and culture to seminarians of IVE, the Institute of the Incarnate Word. This is an order of priests, religious and of lay people (in a 3rd order) founded 32 years ago in Argentina and which has seminaries in the US (in Maryland in the Washington DC conurbation where I visited), in Italy, Brasil, Peru, the Philippines, and in Argentina. They have missions in many parts of the world including Iraq, the Gaza Strip and Papua New Guinea; and monastic foundations in Spain, Argentina, the Middle East and Italy.

An order that embodies the principles of joyful evangelization in accordance in the spirit of Pope St John Paul the Great and Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI.

This past week, I was lucky enough to be invited to give a couple of talks on art and culture to seminarians of IVE, the Institute of the Incarnate Word. This is an order of priests, religious and of lay people (in a 3rd order) founded 32 years ago in Argentina and which has seminaries in the US (in Maryland in the Washington DC conurbation where I visited), in Italy, Brasil, Peru, the Philippines, and in Argentina. They have missions in many parts of the world including Iraq, the Gaza Strip and Papua New Guinea; and monastic foundations in Spain, Argentina, the Middle East and Italy.

My visit coincided with their 32nd anniversary on the Feast of the Annunciation (that's how I know precisely how long they have been going).It was celebrated at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington DC. The celebrant was Bishop Quinn of Winona, MN. He and his Vicar General who flew in for the day just to celebrate Mass for IVE (IVE has a minor seminary in Bishop Quinn’s diocese). Cardinal McCarrick, Archbishop Emeritus of Washington DC spoke at the Mass (all three attended the very festive celebration meal at the seminary afterwards). This was a beautiful and dignified Mass in which the choir of seminarians and sisters from the order chanted Gregorian Mass IX for the Ordinary of the Mass and the music included beautifully sung and moving polyphony.

Before I go on, I should declare a personal bias. I became aware of them for the first time only a few months ago, because a parishioner from one of their parishes in San Jose contacted me and said that the priest there, a member of this order, was quoting my book the Way of Beauty in his homilies and encouraging people to read it because it reflected, he said, the charism of the order. Naturally I was excited and curious and got in touch, and given this interest in my book have a natural in what they are doing.

As a result of this initial contact I was asked to speak about the Way of Beauty to the priests, seminarians and sisters who live at the seminary. I was very happy to do so, of course, but my feeling as I came away from these three days I was the one who benefited the most, through my contact with them, worshiping and praying with them and through the many conversations I had.

There are so many good things I could say about my experiences in the last few days, but rather than list them all (perhaps various aspects will come out in different blog posts in time) I encourage people to read about them in their website and especially the description of their charism. My personal impression is that the qualities of joy, vigor and dignity that come through in the description of their charism is there in each person that I met. Their liturgy is solemn and dignified, their intellectual formation is rigorous and is centered on the philosophy and theology of St Thomas, and they have a special devotion to Our Lady,

Above: celebration of Mass by Cardinal McCarrick at the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception last year. The image is Our Lady of Lujan (see below)

I want to highlight one example of what I saw that I think says a great deal about IVE. In the seminary in Washington DC there were priests, 40 or so seminarians and perhaps a similar number of sisters. I met people from Argentina, the US, Colombia, Ireland, Mexico, El Salvador, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, England, and Australia that I can remember. Most were young (under 35), however, I noticed a number of men with grey hair (or very little hair) and assumed that they were long time members of the order. It was only as I started to talk to them that I found out that some were seminarians studying for the priesthood as well.

One whom I spoke to quite a bit was was 68 years old, currently a deacon and due to be ordained this May. He described himself not as a late vocation, but rather as a delayed vocation. He said that from the time he was a young boy he had wanted to be a priest and had tried several times but had been thwarted for various reasons at various early stages in the process. Latterly he was barred from being a diocesan priest because he was too old to start. He told me that IVE has a policy of never barring anyone whom they feel has a genuine vocation because of age. This was great for him - he told me he had never been happier. It was also good for the community at the seminary, I felt. It had a balancing effect on the spirit of the community. So that within each year, even the novice years, there were people with more life experience in other ways and this enriched community life for all. These are all good, practical and charitable reasons to have such a policy; but the most important reason for having such an open policy, it seemed to me, was something else. It comes from an understanding of what personal vocation is.

When we are fulfilling what God wants us to be then we contribute in charity, beautifully and gracefully to all around us. That man's personal vocation began the moment he entered that order and was on the path that God had set out for him. This means that in the economy of grace he is giving to all around him, as well as receiving. It would be easy for IVE to think of the training period in the seminary is one in which they make the investment of money and time in his training, and only when he is ordained they start to reap the rewards. If that were so, then it would make no sense to take on older seminarians, because they won't have time as priests to pay back the investment made in them (however you would measure such a thing). However, when the economy of grace is brought into the equation, we can see that IVE has to benefit from anyone in their presence who is living out their personal calling in life. It is an act of faith on the part of IVE that trusts in the principle that God will provide for us if we do God's will and help others to God's will too.

You can find out more information about IVE in the US by visiting iveamerica.org. If you want to see the home site for the organization based in Argentian (in Spanish) then that is iveargentina.org.

Below: Our Lady of Lujan, patroness of Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay. She is the patroness of the order too. The story of the beginning of the special veneration of this image of the Immaculate Conception, dating from 1630 when a miracle occured is here. I didn't know until I saw this image that the national flags and colors of the shirts of the national soccer teams of Argentian and Uruguay are in the colors of Our Lady of Lujan. (Perhaps England could take a leaf out of Argentina's book, have their soccer team wear the color of Our Lady of Walsingham, and then we might win the World Cup again!)

For information on the iconography of the Immaculate Conception see and article I wrote here.

Vocation and the Common Good

How doing what I want to do helps others to do what they want - a tribute to the outgoing President of the Dominican School of Theology and Philosophy in Berkeley, CA Several years ago, I attended a short lecture series offered by Fr Michael Sweeney, who was president of the Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology a member school of the Graduate Theological Union at Berkeley). It was called Re-Visioning Society and was offered as part of their summer session and explored Catholic social teaching and the common good. I am reminded of this now, in 2015, because I have stayed in touch with Fr Sweeney ever since. He has just stepped down from his role as President after 10 years. I am sure he will continue to have a profound affect people's lives in this next phase of his life. I hope also, of course, that the incoming President continues and even builds on the good work that has been going on at the school.

I was interested Fr Sweeney's course I because this idea of the common good has been referred to by Pope Benedict in a recent encyclical. What I didn't quite realize beforehand how important what I learned would be on my thinking subsequently. I was excited to realize, as happens so often when I learn more about one aspect of Catholic teaching, that it would have an impact on my understanding of everything else in the Faith. One of those in particular relates to the idea of personal vocation. I had written an article about discerning personal vocation just before this. Here is the article I wrote after the course, 5 years ago, in which (with the aid of Fr Sweeney's lectures) I hoped to place that idea of personal vocation in the context of God’s vocation for the whole human race, the common good:

How doing what I want to do helps others to do what they want - a tribute to the outgoing President of the Dominican School of Theology and Philosophy in Berkeley, CA Several years ago, I attended a short lecture series offered by Fr Michael Sweeney, who was president of the Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology a member school of the Graduate Theological Union at Berkeley). It was called Re-Visioning Society and was offered as part of their summer session and explored Catholic social teaching and the common good. I am reminded of this now, in 2015, because I have stayed in touch with Fr Sweeney ever since. He has just stepped down from his role as President after 10 years. I am sure he will continue to have a profound affect people's lives in this next phase of his life. I hope also, of course, that the incoming President continues and even builds on the good work that has been going on at the school.

I was interested Fr Sweeney's course I because this idea of the common good has been referred to by Pope Benedict in a recent encyclical. What I didn't quite realize beforehand how important what I learned would be on my thinking subsequently. I was excited to realize, as happens so often when I learn more about one aspect of Catholic teaching, that it would have an impact on my understanding of everything else in the Faith. One of those in particular relates to the idea of personal vocation. I had written an article about discerning personal vocation just before this. Here is the article I wrote after the course, 5 years ago, in which (with the aid of Fr Sweeney's lectures) I hoped to place that idea of personal vocation in the context of God’s vocation for the whole human race, the common good:

The questions I was hoping to resolve ran as follows: how can I act in ‘solidarity’ with the ‘common good’ and fulfill a personal vocation at the same time? Does acting for the common good mean that I have to think about how every action is in part, for example, going to contribute to alleviating famine in the world? Or, put another way, if I do nothing directly to help alleviate famine in Africa, am I ignoring my obligation to act in accordance with the common good? If either is so, it seems an impossibly high standard to achieve. Furthermore, won’t it likely undermine my success at doing anything well because I will have to spread myself too thinly – if I devote the time needed to teaching at Thomas More College, plus the other duties of life, I have none left to use directly to help those starving in the horn of Africa. Is this wrong? Am I being selfish in being and artist because I love doing it?

The course began by establishing from reason (as distinct from revelation) the nature of the human person as a relational being. We were simply asked to give a short summary of who we were for the other members of the class.

At this point I must admit I was wondering if I’d done the right thing in signing up for the class. Was it was going to degenerate into a touchy feely therapy? I needn’t have worried however. After allowing each of us to speak, Fr Sweeney then remarked on a common thread that ran through our descriptions of ourselves. Our own sense of ourselves was based upon relationships we have with others. (For example, ‘I work with this company’ ‘I do this job with these people’ ‘I am a father’) This is, we were told, what describes a person, as distinct from an individual. A human person is always in relation with others, starting from birth. No one, by choice, disengages from society altogether (not even a hermit) and is happy. From this starting point in common experience, he built up rationally, the case he was making, taking us with him…

This understanding of the human person has a profound effect on how we view what society is. A relationship of the sort we are now envisioning is always between two subjects ie two people freely cooperating as moral agents. This is termed covenantal and is based upon mutual self-sacrifice on behalf of the other. This freedom to respond as a person is one of the essential elements of society. Society therefore is the vector sum of the relationships within it. It is not a collective of self-contained individuals.

As with all things that exist in human nature, the essence of personhood exists in perfection in God in whose image and likeness we are made. However, there is only one God and unlike us He is complete unto Himself and does not rely on any external relationships in order to exist. Revelation helps us here: through it we know that there is one God and three persons in the Trinity, in perfectly realized relationship. This Christian concept of God also explains why we are liturgical beings, first and foremost. We are made for the liturgy, by which we approach the Father, through the Son, in the Spirit. When we participate in the liturgy we enter the Church, the mystical body of Christ. When we do so, with grace, we can relate first to the Son as man; and second to the Father through the Son as God. The Son is one person, but two natures.

If God were not like this, our relationship with him would be very different. A God who is not personal in the Christian sense would always be above us. We could not be raised to Him. Instead of a relationship of two subjects, it would be one of subject and object that is, master and slave. One can immediately see why Judeo-Christian society is fundamentally different from Islamic understanding of society, for example.

The good is what we seek and what makes us happy. We know from revelation objectively that this is God. This is the ultimate Good that is common to all of us. Society as a whole is called to be with Him in heaven and simultaneously, each person is called be with Him as well. On the way there are secondary goods that every one of us needs in order to be happy: food, shelter, water, air, love and so on. These are common goods.

So what of personal vocation and common good? God has called each of us to be with Him in heaven, as I described in my previous article, when we follow this we feel the joy that is ours. If we consider the vision that God has for society to be represented by a picture, then each personal vocation is a piece in the jigsaw that contributes to that picture. Therefore, we only need focus on our personal vocation and be content that it is contributing to the big picture and if perfectly realized would be in perfect harmony with it. This is not justifying selfishness. Every vocation is one of charity which permeates all that we do, but the precise way in which we are called to direct that charity is unique to each person. Some will be called to raise money for those who are starving. Some will not, but will be asked to. We are connected to society most profoundly through our closest personal relationships. So whatever these happen to be, these are the ones that we should focus on the most.

This of course, does rely on us being able to discern our vocation. We are fallen people and man’s ingenuity to hide bad motives behind good seems at times limitless. Therefore, good counsel is to be recommended during the discernment process.

When faced with a major choice we can ask ourselves a number of questions that help to point us in the right direction. First, is what I am doing consistent with its proper end? If so I am more likely to completing my piece of the jigsaw. Second (as a safeguard) is what I am proposing to do contrary to common good? Is it undermining others’ ability to respond freely in their relationships, for example; is it polluting the air so that it’s likely to harm those who breathe it. If so, I won’t do it.

Applied in business for example, other things being equal, I would act to make the business as profitable as possible, so that the gross profit was available to pay costs and employees, distribute amongst shareholders and reinvest for the continued profitability of the business. I would not feel obliged, for example, to institute charitable donations by the business to people that would be otherwise unconnected to the business model (although it would be perfectly good to take steps to enable shareholders and individuals to choose to contribute cooperatively in some way that they could not do as individuals). The general principle is that by fulfilling our personal vocation, we will be helping society as a whole to move towards the common good (and by refusing to do so, we tend to frustrate it).

I saying that each person's vocation is unique, what we are referring to is each person's unique way of attaining those goods that are common to all of us. And if in essence our vocation itself is common, and if the essential relationships through which it is expressed our common, then we are necessarily in solidarity with each other as we pursue our own vocation.

And what does this have to do with beauty? Beauty is what we perceive when there is harmonious relationships, sometimes called ‘due proportion’. In the context of human relationships, that is the harmonious alignment of wills on behalf of another and it is called love. An education in beauty is an education in love. It will increase our natural instinct for acting in accordance with the common good for the benefit of all. It starts with God’s love for us, already assured, and the degree to which we respond in kind, through grace.

As St Augustine said: ‘Love God and do what you want.’ And even if it means going to the desert and sitting on a pillar it is helping mankind...

Discerning My Vocation as an Artist

How I came to be doing what I always dreamed of

How I came to be doing what I always dreamed of

Following on from the last piece, as mentioned I am reposting an article first posted about four years ago. In connection with that, it is worth mentioning that one's personal vocation can change as we grow older. I am not necessarily set in the same career or life situation for life. What was fulfilling for me as a young man may not be right for me now. So I do think that regular reassessment is something that should be considered.

I wrote this originally because people regularly ask me how they can become an artists. One response to this is to describe the training I would recommend for those who are in a position to go out and get it. You can read a detailed account of this in the online course now available. However, this is only part of it (even if you accept my ideas and are in a position to pay for the training I recommend). It was more important for me first to discern what God wants me to do. I did not decide to become an artist until I was in my late twenties (I am now 52). That I have been able to do so is, I believe, down to inspired guidance. I was shown first how to discern my vocation; and second how to follow it. I am not an expert in vocational guidance, so I am simply offering my experience here for others to make use of as they like.......

I am a Catholic convert (which is another story) but influential in my conversation was an older gentleman called David Birtwistle, who was a Catholic. (He died more than ten years ago now.) One day he asked me if I was happy in my work. I told him that I could be happier, but I wasn’t sure what else to do. He offered to help me find a fulfilling role in life.

He asked me a question: ‘If you inherited so much money that you never again had to work for the money, what activity would you choose to do, nine to five, five days a week?’ One thing that he said he was certain about was that God wanted me to be happy. Provided that what I wanted to do wasn’t inherently bad (such as drug dealing!) then there was every reason to suppose that my answer to this question was what God wanted me to do.

While I thought this over, he made a couple of points. First, he was not asking me what job I wanted to do, or what career I wanted to follow. Even if no one else is in the world is employed to do what you choose, he said, if it is what God wants for you there will be way that you will be able to support yourself. He told me to put all worries about how I would achieve this out of my mind for the moment. Such doubts might stop me from having the courage to articulate my true goal for fear of failure. Remember, he said, that if God’s wants you to be Prime Minister, it requires less than the ‘flick of His little finger’ to make it happen. If wanted to do more than one thing, he said I should just list them all, prioritise them and then aim first for the activity at the top of the list.

I was able to answer his question easily. I wanted to be an artist. As soon as I said it, I partly regretted it because the doubts that David warned me about came flooding in. Wasn’t I just setting myself up for a fall? I had already been to university and studied science to post-graduate level. How was I ever going to fund myself through art school? And even if I managed that, such a small proportion of people coming out of art school make a living from art. What hope did I have? I worried that I would end up in my mid-thirties a failed artist with no other prospects. David reassured me that this was not what would happen. This process did not involve ever being reckless or foolish, but I would always need faith to stave off fear.

I was able to answer his question easily. I wanted to be an artist. As soon as I said it, I partly regretted it because the doubts that David warned me about came flooding in. Wasn’t I just setting myself up for a fall? I had already been to university and studied science to post-graduate level. How was I ever going to fund myself through art school? And even if I managed that, such a small proportion of people coming out of art school make a living from art. What hope did I have? I worried that I would end up in my mid-thirties a failed artist with no other prospects. David reassured me that this was not what would happen. This process did not involve ever being reckless or foolish, but I would always need faith to stave off fear.

Next David suggested that I write down a detailed description of my ideal. He stressed the importance of crystallizing this vision in my mind sufficient to be able to write it down. This would help to ensure that I spotted opportunities when they were presented to me. Then, always keeping my sights on the final destination, I should plan only to take the first step. Only after I have taken the first step should I even think about the second. Again David reiterated that at no stage should I do anything so reckless that it may cause me to let down dependants, to be unable to pay the rent or put food on the table.

The first step, he explained, can be anything that takes me nearer to my final destination. If I wasn’t sure what to do, he told me to go and talk to working artists and to ask for their suggestions. There are usually two approaches to this: either you learn the skills and then work out how to get paid for them; or even if you have to do something other than what you want, you put yourself in the environment where people are doing it. For example, he suggested that I might get a job in an art school as an administrator. My first step turned out to be straighforward. All the artists I spoke to told me to start by enrolling for an evening class in life drawing at the local art school.

My experience since has been that I have always had enough momentum to encourage me to keep going. To illustrate, here’s what happened in that first period: the art teacher at Chelsea Art School evening class noticed that I liked to draw and suggested that I learn to paint with egg tempera. I tried to master it but struggled and after the class was finished I told someone about this. He happened to know someone else who, he thought, worked with egg tempera. He gave me the name and I wrote asking for help. About a month later I received a letter from someone else altogether. It turned out that the person I had written to was not an artist at all, but had been passed the letter on to someone who was called Aidan Hart. Aidan was an icon painter. It was Aidan who wrote to me and who invited me to come and spend the weekend with him to learn the basics. Up until this point I had never seen or even heard of icons. Aidan eventually became my teacher and advisor.

There have been many chance meetings similar to this since. And over the course of years my ideas about what I wanted to do became more detailed or changed. Each time I modified the vision statement accordingly, and then looked out for a new next step – when I realized that there was no school to teach Catholics their own traditions, I decided that I would have to found that school myself and then enlist as its first student. Later it dawned on me that the easiest way to do thatwas to learn the skills myself from different people and then be the teacher.

There have been many chance meetings similar to this since. And over the course of years my ideas about what I wanted to do became more detailed or changed. Each time I modified the vision statement accordingly, and then looked out for a new next step – when I realized that there was no school to teach Catholics their own traditions, I decided that I would have to found that school myself and then enlist as its first student. Later it dawned on me that the easiest way to do thatwas to learn the skills myself from different people and then be the teacher.

I was also told that there were two reasons why I wouldn’t achieve my dream: first, was that I didn’t try; the second was that en route I would find myself doing something even better, perhaps something that wasn’t on my list now. When this happens you will be enjoying so much you stop looking further.

David also stressed how important it was always to be grateful for what I have today. He said that unless I could cultivate gratitude for the gifts that God is giving me today, then I would be in a permanent state of dissatisfaction. In which case, even if I got what I wanted I wouldn't be happy. This gratitude should start right now, he said, with the life you have today. Aside from living the sacramental life, he told me to write a daily list of things to be grateful for and to thank God daily for them. Even if things weren’t going my way there were always things to be grateful for, and I should develop the habit of looking for them and giving praise to God for his gifts. He also stressed strongly that I should constantly look to help others along their way.

As time progressed I met others who seemed to be understand these things. So just in case I was being foolish I asked for their thoughts. First was an Oratorian priest. He asked me for my reasons for wanting to be an artist. He listened to my response and then said that he thought that God was calling me to be an artist. Some years later, I asked a monk who was an icon painter. He asked me the same questions as the Oratorian and then gave the same answer.

What was interesting about all three people so far is that none of them asked what seemed to be the obvious question: ‘Are you any good at painting?’ I asked the monk/artist why and he said that you can always learn the skills to paint, but in order to be really good at what you do you have to love it.

Some years later still, when I was studying in Florence, I went to see a priest there who was an expert in Renaissance art. It was for his knowledge of art that I wanted to speak to him, rather than spiritual direction. I wanted to know if my ideas regarding the principles for an art school were sound. He listened and like the others encouraged me in what I was doing. Three years later, after yet another chance meeting, I was offered the chance to come to Thomas More College of Liberal Arts in New Hampshire, to do what precisely what I had described to the priest in Florence.

In my meeting with him the Florentine priest remarked in passing, even though I hadn’t asked him this, that he thought that it was my vocation to try to establish this school. He then said something else that I found interesting. He warned me that I couldn’t be sure that I would ever get this school off the ground but he was certain that I should try. As I did so, my activities along the way would attract people to the Faith (most likely in ways unknown to me). This is, he said, is what a vocation is really about.

Praying the Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours teaches us how to discerning God's will

Liturgical prayer is a means for discerning our personal vocation and God’s will for us…and so much more In the Lenten readings from the Liturgy of the Hours we have an example how through the Liturgy the Church instructs us about the value of praying the Liturgy with the Church. The reading from Vespers on Monday of weeks 1 and 2 in Lent reads:

‘My brothers, I implore you by God’s mercy to offer your very selves to him: a living sacrifice, dedicated and fit for his acceptance, the worship offered by mind and heart. Adapt yourselves no longer to the pattern of this present world, but let your minds be remade and your whole nature thus transformed. Then you will be able to discern the will of God, and to know what is good, acceptable and perfect.’ (Rom 12:1-2)

Liturgical prayer is a means for discerning our personal vocation and God’s will for us…and so much more In the Lenten readings from the Liturgy of the Hours we have an example how through the Liturgy the Church instructs us about the value of praying the Liturgy with the Church. The reading from Vespers on Monday of weeks 1 and 2 in Lent reads:

‘My brothers, I implore you by God’s mercy to offer your very selves to him: a living sacrifice, dedicated and fit for his acceptance, the worship offered by mind and heart. Adapt yourselves no longer to the pattern of this present world, but let your minds be remade and your whole nature thus transformed. Then you will be able to discern the will of God, and to know what is good, acceptable and perfect.’ (Rom 12:1-2)

This passage is telling us in order to discern the will of God, we ought to make a ‘living sacrifice’ of ourselves. That living sacrifice is specifically our worship of God, that is, our participation in the liturgy - the Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours. What makes this living sacrifice ‘worthy and fit for his acceptance’ is that it is a participation in the only living sacrifice than can have that high worth, that is the sacrifice of Christ himself. There is only an upside to this. We get a free ride - we pray the liturgy, and in so doing open ourselves up to the reception of all the benefits of the supreme act of living made by someone else, without experiencing any of the pain. Christ bears all of that. It is an absurdly one-sided arrangement in our favour. It is such good news that it is scarcely believable, yet this is truly what we are offered through the Church. There is a standing offer already made, and our prayer is the act of acceptance.

Then, just in case we doubted that this living sacrifice is the prayer of the Church, we read the next morning in the Office of Readings a commentary by St Augustine on Psalm 140, 1-2. The Psalm passage he is commenting on reads as follows:

Then, just in case we doubted that this living sacrifice is the prayer of the Church, we read the next morning in the Office of Readings a commentary by St Augustine on Psalm 140, 1-2. The Psalm passage he is commenting on reads as follows:

‘I call upon you O Lord, listen to my prayer, Give ear to the voice of my supplication when I call to you.

Let my prayer be counted as incense before you, And the lifting up of my hands as an evening sacrifice.’

Within the commentary he explicitly makes the connection between the sacrifice and prayer of the faithful as part of the body of Christ, that is, the liturgy. He also explains how the pain and anguish that Christ felt in his passion is due to His bearing our sins and agony. The blood that streamed over his body when experiencing the agony in the garden was not due to anxiety for himself but, says Augustine: ‘Surely this bleeding of all his body is the death agony of all the martyrs of his Church’. We have just had the Feast of the martyrs Perpetua and Felicity. What is so striking the account of their deaths (again given in the Office of Readings) is how cheerfully and gracefully they bore the grevious mutilations that eventually killed them. I wonder at their purity and cooperation with grace and I wonder also at the fact that this pain is what Christ is choosing to experience on their behalf.

Augustine goes on to encourage us by saying that this is available to all of us: ‘All of us can make this prayer; this is not merely my prayer; the entire Christ prays in this way. But it is made rather in the name of the body…The evening sacrifice, the passion of the Lord, the cross of the Lord, the offering of a saving victim, the whole burnt offering acceptable to God; that evening sacrifice produced in his resurrection from the dead, a morning offering. When a prayer is sincerely uttered by a faithful heart, it rises as incense rises from a sacred altar. There is no scent more fragrant than that of the Lord. All who believe must possess this perfume.’

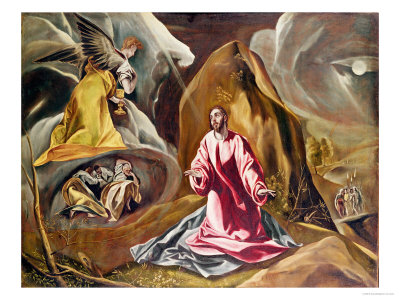

Paintings by, from top: El Greco, Rubens and Titian

The Pope and the CEO - John Paul II's Leadership Lessons to a Young Swiss Guard

Here's a great book about discovering your personal vocation and how to work towards it. It is written by Andreas Widmer who is both the young Swiss Guard and the not-quite-so-young CEO referred to in the title. This book is simple and short (just 150 pages) but powerful. He engages us with many great anecdotes of the great Pope that illustrate his points and reveal insights into the man’s personality that I was not aware of before. It was also interesting just to find what a Swiss Guard does (apart from standing still for tourists wearing striped baggy trousers).

He builds on these tales with his subsequent experience as a businessman. There are valuable practical lessons for businessmen here, but it is wider reaching than that. It is as much about the realisation of personal vocation (Andreas's happens to be that of a businessman) and so is, potentially, of interest to everyone.

Here's a great book about discovering your personal vocation and how to work towards it. It is written by Andreas Widmer who is both the young Swiss Guard and the not-quite-so-young CEO referred to in the title. This book is simple and short (just 150 pages) but powerful. He engages us with many great anecdotes of the great Pope that illustrate his points and reveal insights into the man’s personality that I was not aware of before. It was also interesting just to find what a Swiss Guard does (apart from standing still for tourists wearing striped baggy trousers).

He builds on these tales with his subsequent experience as a businessman. There are valuable practical lessons for businessmen here, but it is wider reaching than that. It is as much about the realisation of personal vocation (Andreas's happens to be that of a businessman) and so is, potentially, of interest to everyone.

I have written before, here, about how I was inspired to believe that if we have faith enough to believe it possible, that a life of joy and abundance is possible for everyone. Much of what I read confirmed the guidance that I was given, and much adds something new and useful to it.

He describes very well the different types of vocation and how every single person has a personal vocation that offers them a life of joy and fulfilment. Every aspect of our life can be ordered to this calling and ultimately everything is ordered to love of God and our fellows on our final destination of union with God in heaven. It is our joy in the journey that will do so much to attract others to the Catholic life.

What is particularly good is how he tackles head on the question of earthly and material success. So many assume, I think, that we should aim to be as poor as we can and those who are wealthy are somehow less holy.

What is particularly good is how he tackles head on the question of earthly and material success. So many assume, I think, that we should aim to be as poor as we can and those who are wealthy are somehow less holy.

Widmar presents a different picture. Riches empower us to do what we are meant to do and so some need these things in order to be able to fulfil their vocation. It is a modern day noblesse oblige - the balancing of privilege with responsibility. He stresses how important it is that striving for these things doesn't detract us from our ultimate calling and the wealthier we are, the more important it is to develop detachment through personal discipline and, as mentioned before cultivating a joy in life that ensures that we do not rely on anything other than God to make us happy. If we strive for these things then we can be the example that draws others to the faith.

I enjoyed his explanation of how the spiritual life is not a handicap to business, even in worldly terms but rather, it is an asset. For those whose vocation is to be a businessman (an important qualification) then following the path of holiness in business will tend to encourage the flourishing of that business. If God intends someone to be wealthy, then holiness will increase their chance of success. It will enhance creativity, resourcefulness, efficiency and importantly more competitiveness.

This is contrary to a commonly held view that making money by carrying out the core business activities cannot be harmony with those actions that promote a more caring 'person-centred'' business; and leads to the assumption that a business must necessarily compromise profitability in order to care properly for its employees and customers. The message that I take from Widmer's book (and he speaks with some authority as an experienced and successful businessman) is that when the conduct of the those in the business reflects good values, it will add value to the goods and services offered; and give a company a greater competitive edge.

Widmer stresses need for prudence and guidance in making decisions where the options both seem morally sound. In other words how do I know not just what is good, but what it the best. He gives good advice in facing these situations.

There is perhaps more that could be said on how to improve prudence and creativity so that our actions are in closer harmony with the cosmos and the beauty of the Trinity: and that is through a traditional education in beauty. Also in regard to ordering the different aspects of our personal vocation, it is useful to take into account that man is made to worship God - it is intrinsic to his being. The liturgy is the earthly bridge to the heavenly realm, so if we are seeking to conform anything that we do to our heavenly end, then it will be a great help if liturgical principles come into play. These are small points in the context of the whole book and it's not surprising that they occur to me, as they are my particulary personal interests... so I would say that wouldn't I! So overall this is a great book and strongly recommended.

See more about the book and order a copy at www.thepopeandtheceo.com.