New Info, How to Join Us in Lockdown Prayer! Choral Evensong, Live Each Day, 4:45 pm PST - How To Join Us

Asperges Syndrome

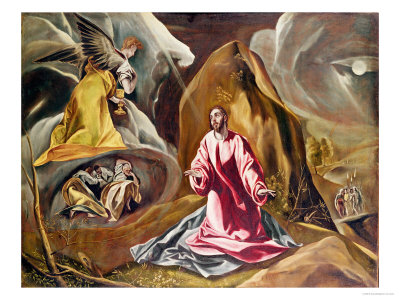

How to Pray With Sacred Art

The short answer to this question is just this: pray as you would normally, but look at sacred art as you do it. Good sacred art will promote a right attitude through the combination of content, compositional design, and stylistic elements. In this sense, the artist does the hard work in advance to make it easy and natural for us.

What is the cause of the Pope Francis effect? It is nothing new. On the contrary, it is his conformity to tradition!

He is a model of the New Evangelization that we can all imitate. After his visit to the United States, the sense is that Pope Francis has done a remarkable job in connecting with people beyond the Church. True, there is constant argument about what he actually says, what people want him to say and what he really means. But despite the confusion no one can doubt that he has a knack for connecting with people. Just today, as I write this, I had a spam email from a political candidate who is, as far as I know, an avowed socialist asking me to vote for him with a connection to a speech he made praising Pope Francis because of his concern for the poor. (I am not entitled to vote for anyone in the US incidentally so he had wasted his time even if I agreed with thim). It is interesting that this should happen despite the fact that Pope Francis has repeatedly condemned socialism and a the fact the the candidate wants to use Francis to push his agenda, indicates how strong his public image is. My reaction to this was to think that this is not an argument for me to vote for socialism, as the candidate thinks; but rather one for the socialists to realise that their aims would be better met if they converted to Catholicism! Stranger things have happened!

I am presenting three articles about him to mark the occasion of his visit, sparked off by a conversation with a friend who told me that she had noticed how many of her friends, especially non-Catholics seemed to warm to him. We were asking ourselves why he is so popular. Is it really just that the non-Catholics like him because he sounds as though he is reversing Catholic teaching? I don't think so as you'll see. You will see that I am largely still optimistic about the Franciscan papacy. I do hope that I feel the same after the synod on the family which is taking place as speak :)

Two of these three contain some things I have written before, but represented in this new context.

How does he do it? The answer, I believe is quite simple and it is nothing to do with PR tactics or political spinning if ever there was a Pope that really seemed less interested and less skilled in the art of polished media manipulation it is this one. Rather, to the degree that he is connecting with people and drawing them to the truth, what is drawing people in is supernatural.

Those who do not believe in the supernatural will not account for it in this way, even if they like him, but that doesn't invalidate the point. I suggest that what we see here is a case of the New Evangelization at work. For Catholics it works like this - or rather it ought to if we followed the Church's teaching: by our participation in the sacramental life, we are transformed supernaturally so that we partake of the divine nature. By degrees in this life, and fully in the next, we enter into the mystery of the Trinity, relating personally to the divine godhead by being united to the mystical body of Christ, the Church. When this happens we shine with the light of Truth as Christ did at the Transfiguration - people see beauty and love in our daily actions because they are, quite literally, graceful. They see the joy in our lives. This is what people are seeing in Pope Francis, I suggest. And here is the great fact that so often seems to be missed, the Pope is not especially blessed in participating in this. On the contrary, what he is showing us something that is available to every single one of us, low or high. This is what he wants us to believe.

How do we get this. The place of transformation, if I can put it like that, is our encounter with God in the sacred liturgy, most especially the Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours with the Eucharist at its heart. All of the Christian life is consummated in this life by our worship of God. It is by accepting the love of God first, and most powerfully in the sacred liturgy, that we are transformed into lovers who are capable of loving our fellow man and the Franciscan way.

This message is precisely the same as Pope Benedict XVI and John Paul II before him. In this sense Francis is utterly traditional. He is, I suggest, able to be the Pope of evangelization because he comes after the work of these two great Popes who did so much, beginning with John Paul II, in the chaotic aftermath of Vatican II to implement the true message of the council. Contrary to what is often reported, he does not stand out against his predecessors. Rather, in his own way, he is in conformity with them.

Let us take the case in point. What is his view on the liturgy and the need for supernatural transformation. His words and actions indicate that he understands that all Benedict XVI did was not only necessary, but he now wants to continue in the same vein. This may be a surprise to many, but this is why I think so.

I have heard some express disappointment that there was not enough emphasis on the liturgy in the apostolic exhortation of Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium. It is true that there is little direct reference to the liturgy, and so it might appear at first sight that there is little interest from the Pope on this matter.

I have no special access to the personal thoughts of the Holy Father beyond what is written, so like everyone else, I look at the words and ask myself what they mean. In doing this, given that the Holy Father is for the most part articulating general principles, and given that I am not in a position to ask him directly, I am forced to interpret and ask myself what does he mean in practice? And then the next question I ask myself is this: to what degree does this change what the Church is telling me I ought to do? Or rather is he simply directing my attention to an already existing aspect of Church teaching that he feels is currently neglected?

If I want to, of course, I can choose to look at it the Exhortation as a manifesto in isolation and assume that is the sum total of all that the Pope believes; or I can choose to see this in the context of a hermeneutic of continuity. In other words I will assume that in order to understand this document, I must read read it as a continuation of those that went before, and this means most especially the period just before the advent of Pope Francis, that is, the documents of the papacy of Pope Emeritus Benedict. So unless I see something that contradicts them, I will assume that they are considered valid and important still.

If we read it this way, then because he doesn't have much to say on any particular issue, it doesn't mean that he opposes it, or even that he thinks it is unimportant, rather it means that he feels that what is appropriate has already been said and so has little or nothing to add.

This is what traditionalists within the Church say that the liberals failed to do after Vatican II. Sacrosanctum Concilium must be read, we have been told (and I think quite rightly) in the context of what went before to be properly understood; and is one reason why Pope Benedict XVI encouraged celebration of the Extraordinary Form of the Mass - so the people could learn from and experience of that context, so to speak. I accept this argument fully, and therefore, it seems reasonable to read the writings of the new Pope in this way too.

Now to Evangelii Gaudium and the liturgy. The following paragraph appears:

'166. Another aspect of catechesis which has developed in recent decades is mystagogic initiation.[128] This basically has to do with two things: a progressive experience of formation involving the entire community and a renewed appreciation of the liturgical signs of Christian initiation. Many manuals and programmes have not yet taken sufficiently into account the need for a mystagogical renewal, one which would assume very different forms based on each educational community’s discernment. Catechesis is a proclamation of the word and is always centred on that word, yet it also demands a suitable environment and an attractive presentation, the use of eloquent symbols, insertion into a broader growth process and the integration of every dimension of the person within a communal journey of hearing and response.'

So what is mystagogical initiation? What the Pope is saying seems to me be referring to and reiterating what was said in the apostolic exhortation written by Pope Emeritus Benedict, Sacramentum Caritatis. This is headed 'On the Eucharist as the Source and Summit of the Church's Life and Mission' and was written following a synod of bishops (I don't know, but I'm guessing the Pope Francis was present). In a section entitled 'Interior participation in the celebration' we have a subheading 'Mystagogical catechesis' in which the views of the gathered bishops are referred to specifically:

'64. The Church's great liturgical tradition teaches us that fruitful participation in the liturgy requires that one be personally conformed to the mystery being celebrated, offering one's life to God in unity with the sacrifice of Christ for the salvation of the whole world. For this reason, the Synod of Bishops asked that the faithful be helped to make their interior dispositions correspond to their gestures and words. Otherwise, however carefully planned and executed our liturgies may be, they would risk falling into a certain ritualism. Hence the need to provide an education in eucharistic faith capable of enabling the faithful to live personally what they celebrate.'

This is so important that the following paragraph was included also:

c) Finally, a mystagogical catechesis must be concerned with bringing out the significance of the rites for the Christian life in all its dimensions – work and responsibility, thoughts and emotions, activity and repose. Part of the mystagogical process is to demonstrate how the mysteries celebrated in the rite are linked to the missionary responsibility of the faithful. The mature fruit of mystagogy is an awareness that one's life is being progressively transformed by the holy mysteries being celebrated. The aim of all Christian education, moreover, is to train the believer in an adult faith that can make him a "new creation", capable of bearing witness in his surroundings to the Christian hope that inspires him.' [my emphases]

I don't think it is possible to make a stronger statement on the centrality of the liturgy to the life of the Church and the importance of the faithful understanding this and deepening their participation in it. There is no reason to believe that Pope Francis is dissenting from this, in fact quite the opposite - he seems to be referring directly to it and re-emphasising it. If this is what he doing, then he might be stressing the liturgy in a way that even some Catholic liturgical commentators do not. (Indeed, one wonders if the first step in mystagogical catechesis for many is one that begins by explaining the meaning of the phrase 'mystagogical cathechesis'!)

I wonder also how many Catholic colleges and universities (I am thinking here of those that consider themselves orthodox) actually make mystagogy the governing principle in the design of their curricula? How many Catholic teachers, regardless of the subject they are teaching, consider how what they are teaching relates to it? If we believe what Pope Benedict wrote (and Francis appears to be referring to) then if I can't justify what I teach in these terms, then it isn't worth teaching.

Am I choosing to interpret Pope Francis the way I wish to see it too? Perhaps - like most people I would always rather that others agreed with me than the other way round. Only future events will demonstrate if I am correct. However, his papacy so far seems to support this picture: while there are some new things, I have read nothing that that explicitly rejects anything that developed during the previous papacy (that's not to say that he hasn't said things that could be interpreted that way if we chose to). In fact, the signs seem to indicate the reverse: his appointment as the Prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments has told us the he was directed explicitly by Pope Francis, to 'continue the good work in the liturgy started by Pope Benedict XVI,' He has broadened and strengthened the mission of the Anglican Use Ordinariate, which is all about enrishment of the liturgy in the English vernacular. I wrote about this in an article 'Has Pope Francis saved Western culture?'. And I have read articles in the New Liturgical Movement website and elsewhere heard anecdotal evidence that he has rejected direct appeals from deputations of emboldened liturgical liberals asking him to ban the Extraordinary Form and celebrating the Mass ad orientem (I attended at a papal Mass in St Peters that was celebrated by him in Latin two years ago).

His personal preferences may not be precisely the same as mine, and I will freely admit that in some of the specifics of matters where I am not bound to agree with him - matters of science and politics for example. But in but in his reinforcement of matters of the Faith, I don't hear anyone telling me that the views I had three years ago need to be changed at all. So in regard to liturgy, art, music and even free market economics (despite the alarm of many), I see nothing as yet that worries me at all...quite the opposite.

Discerning My Vocation as an Artist

How I came to be doing what I always dreamed of

How I came to be doing what I always dreamed of

Following on from the last piece, as mentioned I am reposting an article first posted about four years ago. In connection with that, it is worth mentioning that one's personal vocation can change as we grow older. I am not necessarily set in the same career or life situation for life. What was fulfilling for me as a young man may not be right for me now. So I do think that regular reassessment is something that should be considered.

I wrote this originally because people regularly ask me how they can become an artists. One response to this is to describe the training I would recommend for those who are in a position to go out and get it. You can read a detailed account of this in the online course now available. However, this is only part of it (even if you accept my ideas and are in a position to pay for the training I recommend). It was more important for me first to discern what God wants me to do. I did not decide to become an artist until I was in my late twenties (I am now 52). That I have been able to do so is, I believe, down to inspired guidance. I was shown first how to discern my vocation; and second how to follow it. I am not an expert in vocational guidance, so I am simply offering my experience here for others to make use of as they like.......

I am a Catholic convert (which is another story) but influential in my conversation was an older gentleman called David Birtwistle, who was a Catholic. (He died more than ten years ago now.) One day he asked me if I was happy in my work. I told him that I could be happier, but I wasn’t sure what else to do. He offered to help me find a fulfilling role in life.

He asked me a question: ‘If you inherited so much money that you never again had to work for the money, what activity would you choose to do, nine to five, five days a week?’ One thing that he said he was certain about was that God wanted me to be happy. Provided that what I wanted to do wasn’t inherently bad (such as drug dealing!) then there was every reason to suppose that my answer to this question was what God wanted me to do.

While I thought this over, he made a couple of points. First, he was not asking me what job I wanted to do, or what career I wanted to follow. Even if no one else is in the world is employed to do what you choose, he said, if it is what God wants for you there will be way that you will be able to support yourself. He told me to put all worries about how I would achieve this out of my mind for the moment. Such doubts might stop me from having the courage to articulate my true goal for fear of failure. Remember, he said, that if God’s wants you to be Prime Minister, it requires less than the ‘flick of His little finger’ to make it happen. If wanted to do more than one thing, he said I should just list them all, prioritise them and then aim first for the activity at the top of the list.

I was able to answer his question easily. I wanted to be an artist. As soon as I said it, I partly regretted it because the doubts that David warned me about came flooding in. Wasn’t I just setting myself up for a fall? I had already been to university and studied science to post-graduate level. How was I ever going to fund myself through art school? And even if I managed that, such a small proportion of people coming out of art school make a living from art. What hope did I have? I worried that I would end up in my mid-thirties a failed artist with no other prospects. David reassured me that this was not what would happen. This process did not involve ever being reckless or foolish, but I would always need faith to stave off fear.

I was able to answer his question easily. I wanted to be an artist. As soon as I said it, I partly regretted it because the doubts that David warned me about came flooding in. Wasn’t I just setting myself up for a fall? I had already been to university and studied science to post-graduate level. How was I ever going to fund myself through art school? And even if I managed that, such a small proportion of people coming out of art school make a living from art. What hope did I have? I worried that I would end up in my mid-thirties a failed artist with no other prospects. David reassured me that this was not what would happen. This process did not involve ever being reckless or foolish, but I would always need faith to stave off fear.

Next David suggested that I write down a detailed description of my ideal. He stressed the importance of crystallizing this vision in my mind sufficient to be able to write it down. This would help to ensure that I spotted opportunities when they were presented to me. Then, always keeping my sights on the final destination, I should plan only to take the first step. Only after I have taken the first step should I even think about the second. Again David reiterated that at no stage should I do anything so reckless that it may cause me to let down dependants, to be unable to pay the rent or put food on the table.

The first step, he explained, can be anything that takes me nearer to my final destination. If I wasn’t sure what to do, he told me to go and talk to working artists and to ask for their suggestions. There are usually two approaches to this: either you learn the skills and then work out how to get paid for them; or even if you have to do something other than what you want, you put yourself in the environment where people are doing it. For example, he suggested that I might get a job in an art school as an administrator. My first step turned out to be straighforward. All the artists I spoke to told me to start by enrolling for an evening class in life drawing at the local art school.

My experience since has been that I have always had enough momentum to encourage me to keep going. To illustrate, here’s what happened in that first period: the art teacher at Chelsea Art School evening class noticed that I liked to draw and suggested that I learn to paint with egg tempera. I tried to master it but struggled and after the class was finished I told someone about this. He happened to know someone else who, he thought, worked with egg tempera. He gave me the name and I wrote asking for help. About a month later I received a letter from someone else altogether. It turned out that the person I had written to was not an artist at all, but had been passed the letter on to someone who was called Aidan Hart. Aidan was an icon painter. It was Aidan who wrote to me and who invited me to come and spend the weekend with him to learn the basics. Up until this point I had never seen or even heard of icons. Aidan eventually became my teacher and advisor.

There have been many chance meetings similar to this since. And over the course of years my ideas about what I wanted to do became more detailed or changed. Each time I modified the vision statement accordingly, and then looked out for a new next step – when I realized that there was no school to teach Catholics their own traditions, I decided that I would have to found that school myself and then enlist as its first student. Later it dawned on me that the easiest way to do thatwas to learn the skills myself from different people and then be the teacher.

There have been many chance meetings similar to this since. And over the course of years my ideas about what I wanted to do became more detailed or changed. Each time I modified the vision statement accordingly, and then looked out for a new next step – when I realized that there was no school to teach Catholics their own traditions, I decided that I would have to found that school myself and then enlist as its first student. Later it dawned on me that the easiest way to do thatwas to learn the skills myself from different people and then be the teacher.

I was also told that there were two reasons why I wouldn’t achieve my dream: first, was that I didn’t try; the second was that en route I would find myself doing something even better, perhaps something that wasn’t on my list now. When this happens you will be enjoying so much you stop looking further.

David also stressed how important it was always to be grateful for what I have today. He said that unless I could cultivate gratitude for the gifts that God is giving me today, then I would be in a permanent state of dissatisfaction. In which case, even if I got what I wanted I wouldn't be happy. This gratitude should start right now, he said, with the life you have today. Aside from living the sacramental life, he told me to write a daily list of things to be grateful for and to thank God daily for them. Even if things weren’t going my way there were always things to be grateful for, and I should develop the habit of looking for them and giving praise to God for his gifts. He also stressed strongly that I should constantly look to help others along their way.

As time progressed I met others who seemed to be understand these things. So just in case I was being foolish I asked for their thoughts. First was an Oratorian priest. He asked me for my reasons for wanting to be an artist. He listened to my response and then said that he thought that God was calling me to be an artist. Some years later, I asked a monk who was an icon painter. He asked me the same questions as the Oratorian and then gave the same answer.

What was interesting about all three people so far is that none of them asked what seemed to be the obvious question: ‘Are you any good at painting?’ I asked the monk/artist why and he said that you can always learn the skills to paint, but in order to be really good at what you do you have to love it.

Some years later still, when I was studying in Florence, I went to see a priest there who was an expert in Renaissance art. It was for his knowledge of art that I wanted to speak to him, rather than spiritual direction. I wanted to know if my ideas regarding the principles for an art school were sound. He listened and like the others encouraged me in what I was doing. Three years later, after yet another chance meeting, I was offered the chance to come to Thomas More College of Liberal Arts in New Hampshire, to do what precisely what I had described to the priest in Florence.

In my meeting with him the Florentine priest remarked in passing, even though I hadn’t asked him this, that he thought that it was my vocation to try to establish this school. He then said something else that I found interesting. He warned me that I couldn’t be sure that I would ever get this school off the ground but he was certain that I should try. As I did so, my activities along the way would attract people to the Faith (most likely in ways unknown to me). This is, he said, is what a vocation is really about.

Listen to this Chant in English

Chant that Competes With Praise and Worship Music! I have been contacted by a seminarian based in Boston called Pat Fiorillo who directs the choir of a young adults group in Boston.

He told me that through his influence of introducing this sort of music at groups he has worked with, he has seen a young people's group chant for the first time ever rather than singing only praise and worship music with the usual guitars and drums.

He sent me this recording of his group of singing the Magnificat to the Way of Beauty psalm tones composed by myself and with the harmonization by Paul Jernberg. They are singing it as a communion meditation for Mass on the Feast of the Assumption recently. The antiphon is composed by Paul Ford (whose work I otherwise know nothing of), but I must say that it sounds good. Pat is clearly working well with them, and I find their chant of the antiphon beautiful. They actually did all of the propers - introit and offertory also from Ford's collection - as well as Kyrie VIII, and Proulx's Missa Simplex.

From what he describes everyone is enthusiastic about singing sacred music and he is pleased to have something that works in English which opens the way for congregations who might be resistant if he insisted on Latin. What is particularly encouraging is that this is a seminarian doing this! I hope this gives us an indication of what are priests will be doing in the future.

[audio mp3="http://wayofbeauty.thomasmorecollege.edu/files/2014/08/Communion-Magnificat.mp3"][/audio]

Beauty for Truth's Sake - A Book Linking Liturgy and Education by Stratford Caldecott

This book is recommended reading for all serious travelers on the via pulchritudinis. It is an argument for the inclusion of the ‘quadrivium’ in education as an important part of the antidote to modernism. I posted this review when the book first came out about three years ago. I re-post it now because my friend Strat is very ill and will most likely not live through the summer. It is by way of a tribute to him and that I would like to draw attention to his work.

Here, Strat pulls together and builds with great insight on themes raised earlier and discussed in issues of the journal of faith and culture, Second Spring, which he c0- edits. I was lucky to be able to contribute some of these articles to this journal myself. The articles of mine are the product of many enjoyable hours of conversation between Strat and myself over the years and I am flattered that he refers to our conversations in the forward to this book.

This book is recommended reading for all serious travelers on the via pulchritudinis. It is an argument for the inclusion of the ‘quadrivium’ in education as an important part of the antidote to modernism. I posted this review when the book first came out about three years ago. I re-post it now because my friend Strat is very ill and will most likely not live through the summer. It is by way of a tribute to him and that I would like to draw attention to his work.

Here, Strat pulls together and builds with great insight on themes raised earlier and discussed in issues of the journal of faith and culture, Second Spring, which he c0- edits. I was lucky to be able to contribute some of these articles to this journal myself. The articles of mine are the product of many enjoyable hours of conversation between Strat and myself over the years and I am flattered that he refers to our conversations in the forward to this book.

Stratford has been one of the main influences on my thinking over the years and one the people who first encouraged me to start writing about my ideas. To the degree that I have done so, I could not have written anything worthwhile without his help. I first went into his office in Oxford 15 years ago looking for help in establishing a new sort of Catholic art school. I had phoned him up out of the blue because someone had told me that he was interested in similar things. He instantly agreed to see me and I travelled up to Oxford from London a week later. In this meeting he patiently listened to me and said that he would like to help me. He then invited me up to Oxford and took me through a week of guided reading and helped me to write the first article I had ever written containing these ideas. This was published in Second Spring and was entitled the Way of Beauty (this is where the name for this blog came from!). I remember two things about this, first of all how slow and difficult writing was for me at that point (I hadn't written an essay for the consideration of others since I was sixteen years old!). Second was how patient he was in molding it, suggesting changes for reasons of both style and unorthodox content in such a way that the elegance and clarity of the prose were improved dramatically, but somehow he preserved the essential ideas in such a way that it was my voice that was talking. Several articles followed this, the next was connecting the patterns of the liturgy to the patterns and beauty of numerical description of the cosmos and was called the Art of the Spheres. It was these articles that caused me to be noticed by Catholic institutions such as my current employer, Thomas More College and by Shawn Tribe when he was looking for an art writer for the New Liturgical Movement website. He opened the door that led to what I do now.

The theme of liturgy and number is one that Strat picks up on in his book here, discussing them in the context of the formation of man in education.

Translated as the ‘four ways’, the quadrivium is the collective phrase for four of the seven liberal arts: number, geometry, harmony (music) and cosmology.

The quadrivium is concerned with the study of cosmic order as a principle of beauty. The patterns and rhythms of the liturgy of the Church reflect this order too. As it is all expressed mathematically it allows for the possibility of the liturgical ordering of all our work - the whole culture - to the divine. The patterns of our days, the dimensions of our buildings, the ordering of our institutions can all be in harmony with heaven, creation and the common good.

Interestingly, Pope Benedict XVI drew our attention to the quadrivium in a recent address about St Boethius, (a patron of this blog). He described Boethius's work in adapting this aspect of Greco-Roman culture into a Christian form of education. Boethius wrote manuals on each of these disciplines.

Stratford describes how at a medieval university, around say 1400AD, students received a Bachelor of Arts for the 'Trivium' or 'three ways' (rhetoric, logic, grammar - the other three liberal arts). After this they progressed onto a Master of Arts by studying the quadrivium. This prepared them for the final and longest stage of study, for a doctorate in for example Theology or Philosophy. For Caldecott does not wish to eliminate or undo progress, but rather to add a unifying principle to all that is good about the developments of the modern world and which binds it to its ultimate purpose, and ours.

In his beautifully clear, penetrating prose he describes how each of these subjects is linked to the traditional idea of beauty. I found the chapter on music particularly interesting in this respect. He even speculates on how these areas could be developed in the light of modern scientific developments, for example in his chapter on the Golden Section.

Then in the final chapter he sets out his stall, explaining how he feels this will benefit modern society. He writes: ‘The modern era can be characterised by a certain outlook shaped in part by the overthrow or displacement of ancient metaphysics. We call this outlook 'secular,' and it may take the form of an extreme form of materialism, though it may also take religious forms...even the protection of religion often takes the form of privatization, with faith being exlcluded from any real influence over public life, morality and technology...The modern person feels himself to be disengaged from the world around him, rather than intrinsically related to it (by family, tribe, birthplace, vocation, and so forth)...'

'This all pervasive modern mentality is what we are up against, in education as everywhere else. So the question is now, what can be done about it, if anything? The Enlightenment is not something you can simply unthink. So how do we combat the negative effects of individualism, without losing the benefits of self-consciousness and rationality? The key lies, I believe in revelation and worship. What defines secularism more than anything is inability to pray, and he modern world in its worst aspects is a systematic attack on worship, an idea that begins with the acknowledgement of a Transcendent that reveals itself in the immanent. [Hans Urs von] Balthasar was right: once we lose the sense of objective beauty, of the Forms of the fabric of the world (confirmed and strengthened by revelation), then the ability to pray goes too. The fully ‘buffered’ self has no Forms to contemplate in the cosmos, no reality higher than itself, it has no God to turn to. Prayer is a vital dimension of fully human living. But while we can all pray on our own, it is always in some sense a community thing. It turns us away from ourselves toward God, and in so doing it turns us toward each other (or should do). In fact human civilization had always been build around an act of worship, a public liturgy. Liturgy (from the Greek leitourgia: public work or duty) technically means any kind of religious service done on behalf of a community. Liturgical prayer is a way of being in tune with our society, with other people. But if we are to renew our civilization by renewing our worship, we must understand also that liturgy is a way of being in tune with the motions of the stars, the dance of atomic particles, and the harmony of the heavens that resembles a great song. And Catholic liturgy takes us even deeper than that. It takes us to the source of the cosmos itself, into the sacred precincts of the Holy Trinity where all things begin and end (whether they know it or not), and to the source of all artistic and scientific inspiration, of all culture.’

These are words that even the colleges who think of themselves as faithfully Catholic should take to heart. How many I wonder, truly integrate the liturgical life with the academic life rather than viewing the liturgy as a supporting player that is practised peripherally, however beautifully, to the activities of the classroom?

Back issues of Second Spring and subscriptions can be obtained online here.

To buy Beauty for Truth's Sake, go through to Amazon.com here.

How Liturgy, Prayer and Intuition Are Connected - Recognition of Pattern and Order

Modern research into how firefighters and nurses respond to a crisis supports the idea that a traditional education in beauty will develop our powers of intuitive decision making.

In a great series of recorded lectures entitled The Art of Critical Decision Making, former Harvard business school professor and current Trustee Professor of Management at Bryant University, Michael A Roberto discusses the importance of intuition in making decisions; and the factors that influence the reliability of our intuitive faculty. He illustrates his points with some striking real-life stories of people relying upon or ignoring intuition (sometimes with dire consequences); and backs up what he says with modern psychological research.

Modern research into how firefighters and nurses respond to a crisis supports the idea that a traditional education in beauty will develop our powers of intuitive decision making.

In a great series of recorded lectures entitled The Art of Critical Decision Making, former Harvard business school professor and current Trustee Professor of Management at Bryant University, Michael A Roberto discusses the importance of intuition in making decisions; and the factors that influence the reliability of our intuitive faculty. He illustrates his points with some striking real-life stories of people relying upon or ignoring intuition (sometimes with dire consequences); and backs up what he says with modern psychological research.

For example, he tells of a number of occasions when nurses in cardiac intensive care units predict that a patient is going to have a heart attack. This is despite the fact that the specialist doctors could see no problem and the standard ways of monitoring the patients' condition indicated nothing wrong either. When such nurses are asked why they think the situation is bad, they cannot answer. As a result their predictions were disregarded. As it turned out, very often and sadly for the people involved, the nurses were right. In order to protect patients in future people started to ask questions and do research on why the nurses could tell there was a problem. What was it they were reacting to, even if they couldn't say initially?

The most dramatic tale he related was of a crack team of firefighters who were specialists in dealing with forest and brush fires and would be helicoptered into any location within a large part of the West to deal with fires when they broke out. The leader of the group was respected firefighter who was a taciturn individual who lead by example. He was not a good natural communicator, but usually this did not matter. One day they responded to a call and went to a remote site in California. When they assessed the situation they discerned the pace of spread of the fire, the direction it was going and so worked out how to deal with it safely. These judgments were important because if they got it wrong the brush fire could move faster than any man could run and they would be in trouble. Initially things went as expected but then suddenly the leader stopped and told everybody to do as he was doing. He threw a match to the ground and burnt an area in the grass of several square yards and then put it out. He then lay down on the burnt patch and waited. When asked why, except to say that he thought they were in danger he was unable to answer - he couldn't articulate clearly the nature of the danger or why this would action help. As a result even though he was respected, his advice was ignored by the team. Suddenly the fire turned and ran straight at them, in the panic the reaction of even these firefighters, was to run. This was the wrong thing to do, as the fire caught them and tragically they died. The only survivor was the leader. He was lying in the already burnt patch that was surrounded by brush fire as it swept through the area, but was itself untouched by the advancing blaze as there was no grass to burn within it. He just waited until the surrounding area burnt itself out and then walked away.

In both cases, the practitioners were experienced people who got it right, but weren't believed by others because people were not inclined to listen to the intuition of others if it couldn't be supported by what they thought was a reasonable explanation.

Dr Roberto describes how research since suggests that it is the level of experience in situ that develops an intuitive sense that is accurate enough to be relied upon. What experience teaches is the ability to spot patterns of events. Through repeated observation they know that when certain events happen, they are usually related to others and in a particular way. Even in quite simple situations the different possible permutations of events would be quite complex to describe numerically and so scientific theorems may have difficulty predicting outcomes based upon them. However, the human mind is good at grasping the underlying pattern of any given situation at an intuitive level, and then can compare with what usually happens by consulting the storehouse of the memory of past events. In these situations described, of the fire and the cardiac unit, all the indicators usually referred to by the text books were within the range of what was considered safe. However, what the experienced nurse and firefighter spotted was a particular unusual combination that pointed to danger. This apprehension of truth was happening at some pre-conscious level and is not deduced step by step, hence their difficulties in articulating the detail of why they felt as they did.

While this ended in disaster at first, lessons were learnt. As a result of this, it was recognized that a good decision making processes ought to take into account at least, the intuition of experienced people. Prof Roberto described how hospitals and firefighters and others learning from them, have incorporated it into their critical decision making processes. This should be done with discernment - intuition is not infallible and the less experienced we are in a particular environment, the less reliable it is so this must be taken into account as well.

It also depends on the person. Some people develop that sense of intuition in particular situations faster than others because the intuitive faculty is more highly developed. This, in my opinion, is where the traditional education in beauty might help. In order to develop our sense of the beautiful, this education teaches us to recognize intuitively the natural patterns and interrelationships that exist in the cosmos. When we do so, we are more highly tuned to its beauty and if we were artists we could incorporate that into our work. For non-artistic pursuits we can still apply this principle of how things ought to be to make our activity beautiful and graceful. Also, we have a greater sense of the cause of lack of beauty, when something is missing and the pattern is incomplete or distorted. In these situations we can see how to rectify the situation. This is the part that would help the firefighter or nurse, I believe. The education I am describing will not replace the specialist experience that gave those nurses the edge, but by deeply impressing upon our souls the overall architecture of the natural order, it will develop the faculty to learn to spot the patterns in particular situations and allow them to develop their on-the-job intuition faster.

The greatest educator in beauty is the worship of God in the liturgy and especially when the liturgy of the hours harmonized with our worship of the Mass with the Eucharist at the center. When we pray well it should engage the whole person, body and soul, in such a way that we conform totally to that cosmic pattern. In our book, The Little Oratory, A Beginner's Guide to Prayer in the Home, I describe both the nature of that pattern and also how in the home we can even reinforce certain aspects of it in the formation of children. In God's plan that intuitive sense is developed to help us in ordering all our daily activities to his plan (which would include potentially firefighting and nursing and indeed most human activity). This development of intuition not only improves decisions made in a crisis, but also makes us more creative. I discuss the connection between intuition and creativity in a past article about creativity in science. Through this at work, in the home or in our worship, we can contribute to a more beautiful culture of living for everyone. This is the hoped for New Evangelization and John Paul II's 'new epiphany of beauty' that draws people to the Faith.

How to Address the Crisis in Fatherhood Head On through Prayer

In this article I describe how it is prayer, above all, that binds families together; and the most powerful form of prayer we can pray in the home is the liturgy of the hours. Furthermore, with the father leading the prayers, we are opening the way for a powerful driving force that has effect not only within the family but also beyond the four walls of our home.

I first posted this exactly three years ago. It was in part a desire to see this home-based driving force for change that lead to the writing of the book on prayer in the home, The Little Oratory.

In this article I describe how it is prayer, above all, that binds families together; and the most powerful form of prayer we can pray in the home is the liturgy of the hours. Furthermore, with the father leading the prayers, we are opening the way for a powerful driving force that has effect not only within the family but also beyond the four walls of our home.

I first posted this exactly three years ago. It was in part a desire to see this home-based driving force for change that lead to the writing of the book on prayer in the home, The Little Oratory.

The word Oratory, incidentally means in English 'House of Prayer'. When I used to go to the London Oratory - the wonderful Catholic church in England whose liturgy was so influential in my conversion - I used to see these words on the walls around the sanctuary: domus mea domus orationis vocabitur. It was a quote from Isaiah 56:7 which is echoed in Matthew's gospel - my house shall be called a house of prayer, says the Lord. This isn't the full quote, I know there's some Latin missing there but I am handicapped by a combination of poor Latin skills and a bad memory; but here's the point, I wanted to include at least part of it because it shows the word 'orationis' - 'of prayer' - so that you can make the connection with the title of the book.

We chose this title because we wanted to communicate the idea that even the most humble house can be transformed into a house of prayer in accordance with the ideal articulated in Isaiah, and just as the London Oratory, in all its wonderful glory does. This is how a house becomes a home, however many people live there. The book we have written, we hope, helps us to fulfill that ideal and it places fathers, when we are talking of families, once more right at the centre of family and in right relationship with all others. As one might say, the father is the head and the mother is the heart. Both are necessary!

I will be doing a series of postings over the next few weeks that draw out themes discussed in more detail in the book. Anyway, here is the article....

In the exercise of the lay office in the liturgy each person participates in the sacrifice made by Christ, the supreme act of love for humanity. When we are advocates in prayer in this liturgical setting, the participation in the liturgy becomes an act of love for those people and communities with which we have a connection. Accordingly, by participating in the liturgy the family members enter into the to the mystical body of Christ who is our advocate to the Father and so participate in that sacrifice and His advocacy, on behalf of the family, too. It is the father who is the head of the family and who is called is called above the others to be in a quasi-priestly role, and is in a special position to be the advocate to God for his family. This role is executed without diminishing or replacing the advocacy of other family members.

This role of the father as advocate to the Father is a tradition that is biblical at its source, as Scott Hahn points out: ‘[In] the Book of Genesis, liturgy was the province of the Patriarchs themselves. In each household, priesthood belonged to the father, who passed the office to his son, ideally the firstborn, by pronouncing a blessing over him. In every household, fathers served as mediators between God and their families’[1] Also, just as at Mass we pray for the head of state, family members might pray for the head of the family (and by extension, to all communities and groups that we belong to).

We hear that there is a crisis of fatherhood at the moment, and for all the ways that this manifests itself in our society, one wonders if at root, part of the cause at least is the loss of this sense of advocacy for the family by one who is assigned that special role. A visible example of this aspect of fatherhood is powerful for children in learning to pray and inspiring them to do so regularly; and valuable for boys especially as a demonstration that prayer is a masculine thing to do.

The liturgical activity of the home is the liturgy of the hours because it need not be done in a church and does not need a priest participating in order to be valid, the lay office is sufficient. The ideal therefore is that the father leads the family in the liturgy of the hours, visibly and audibly. If this were to common practice, I believe it would help to reestablish prayer as something that men do and will promote a genuine, masculine fatherhood as well as encouraging vocations to the priesthood amongst boys through this masculine example of liturgical piety.

The liturgical activity of the home is the liturgy of the hours because it need not be done in a church and does not need a priest participating in order to be valid, the lay office is sufficient. The ideal therefore is that the father leads the family in the liturgy of the hours, visibly and audibly. If this were to common practice, I believe it would help to reestablish prayer as something that men do and will promote a genuine, masculine fatherhood as well as encouraging vocations to the priesthood amongst boys through this masculine example of liturgical piety.

Something that would help to reinforce this is a domestic shrine. This is a visible focus in the home for prayer and the Eastern practice of creating and icon corner is particularly good for this. I will never forget seeing an Orthodox family doing their night prayers in front of the icons. The father led the prayers and all sang together or took their turn singing their prayers in the simple but robust Eastern tones. What impressed me was how all the children right down to the youngest who was four, wanted to take their turns and emulate their father. At one point two of the children argued about whose turn it was and Dad had to come in and arbitrate! They had a small incense burner burning and several long slender orange ochre beeswax candles burning in front of the icons. Each stood in reverence, facing the icon corner, occasionally crossing themselves. All the senses and faculties, it seems were directed for prayer as part of and on behalf of the family.

The families who have resolved to do this say to me that full family involvement is not always possible. It is inevitable that often family members will be too busy to join in and some will not want to. Nevertheless, the father resolved to make it clear that he was committing to regular prayer for the family and that all family members were invited at least to join in, so even if the prayer took place with only the father taking part, he was prepared to make that sacrifice on behalf of his family. And when the father is not with the family, for example if at work, he still strives to follow that liturgical rhythm of prayer and when does so, he does so on behalf of his family still.

I am only recently a father, but even when I was single and I prayed the liturgy of the hours I tried to remember to think of myself as participating in some way on behalf of my wider family and the various social groups that I am a member of, including work. Through my personal relationships, and this is still the case, those groups are present in the liturgy, to some degree, when I am. It is one way I can emulate Our Lord by participating in His sacrifice, and make a sacrifice for those with whom I relate. My hope is that will play a small part in bringing God's grace into these groups of people so that they might become communities supernaturally bound together in love. In my prayers, every morning, I consciously dedicate my liturgical activity to all those groups and with whom I am connected so I think of myself as representing my family, my friends, my work, the Church, social groups and so on, perhaps naming any individuals that are on my mind at that time. if, during the day I am not in a position to recite an hour, which can be often, I try mentally to mark the hour with a small prayer to maintain that sense of rhythm.

Images: top two are both paintings of the Holy Family by Giuseppe Crespi painting around the 1700; below: the Nativity with God the Father and the Holy Ghost by Giambattista Pittoni, Italian, 17th century

[1] Scott Hahn, Letter and Spirit, pub DLT, p28

A Beautiful Pattern of Prayer - the Path to Heaven is a Triple Helix…

...And it passes through an octagonal portal.

...And it passes through an octagonal portal.

Liturgy, the formal worship of the Church - the Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours, the Eucharist at its centre - is the ‘source and summit of Christian life’. We are made by God to be united with him in heaven in a state of perfect and perpetual bliss, a perfect exchange of love. All the saints in heaven are experiencing this and liturgy is what they do. It is what we all are made to do; this how it is the summit of human existence. Our earthly liturgy is a supernatural step into the heavenly liturgy, this unchanging yet dynamic heavenly drama of love between God and the saints; and the node, the point at which all of the cosmos is in contact with the supernatural is Christ, present in the Eucharist. It is more fantastic than anything ever imagined in a sci-fi drama. There is no need to watch Dr Who to see a space-time vortex, when I take communion at Mass (assuming I am in the proper state of grace) I pass through one. And there’s no worry about hostile aliens, that battle is fought and won.

Everything else that the Church offers and that we do is meant to deepen and intensify our participation in this mystery. Through the participation in the liturgy, we pass from the temporal into a domain that is outside time and space. Heaven is a mode of existence where all time, past and future is compressed into single present moment; and all places are present at a single point.

Our participation in this cannot be perfect in this life, bound as we are by the constraints of time and space. We must leave the church building to attend to the everyday needs of life. However, this does not, in principle, mean that we cannot pray continuously. The liturgy is not just the summit of human existence; it is the source of grace by which we reach that summit. In conforming to the patterns and rhythms of the earthly liturgy in our prayer, we receive grace sufficient to sanctify and order all that we do, so that we are led onto the heavenly path and we lead a happy and joyous life. This is also the greatest source of inspiration and creativity we have. We will get thoughts and ideas to help us in choices that we make at every level and which permeate every action we take. Then our mundane lives will be the most productive and fulfilling they can be.

How do we know what these liturgical patterns are? We take our cue from nature, or from scripture. Creation bears the thumbprint of the Creator and through its beauty it directs our praise to God and opens us to His grace. The patterns and symmetry, grasped when we recognize its beauty, are a manifestation of the divine order.

Traditional Christian cosmology is the study of the patterns and rhythms of the planets and the stars with the intention of ordering our work and praise to the work and praise of the saints in heaven. This heavenly praise is referred to as the heavenly liturgy. The liturgy that we participate, which is connected supernaturally to the heavenly liturgy is called the earthly liturgy. The liturgical year of the Church is based upon these natural cycles of the cosmos. By ordering our worship to the cosmos, we order it to heaven. The date of Easter, for example, is calculated according to the phases of the moon. The earthly liturgy, and for that matter all Christian prayer, cannot be understood without grasping its harmony with the heavenly dynamic and the cosmos. In order to help us grasp this idea that we are participating in something much bigger that what we see in the church when we go to Mass, the earthly liturgy should evoke a sense of the non-sensible aspect of the liturgy through its dignity and beauty and especially the beauty and solemnit of the art and music we use with it. All our activities within it: kneeling, praying, standing, should be in accordance with the heavenly standard; the architecture of the church building, and the art and music used should all point us to what lies beyond it and give us a real sense that we are praising God with all of his creation and with the saints and angels in heaven. When we pray in accordance with these patterns we are opening ourselves up to God’s helping hand at just the moment when it is offered. This is the prayer that places us in directly in beam of the heat lamp of God’s grace.

The harmony and symmetry of the heavenly order can be expressed numerically. For example, because of the seven days of creation in Genesis there are seven days in the week (corresponding also to a half phase of the idealised lunar cycle). The Sunday mass is the summit of the weekly cycle. In the weekly cycle there is in addition day, the so-called eighth ‘day’ of creation, which symbolises the new order ushered in by the incarnation, passion, death and resurrection of Christ. Sunday the day of his resurrection, is simultaneously the eighth and first day of the week (source and summit). Eight, expressed as ‘7 + 1’ is a strong governing factor in the Church’s earthly liturgy. (It is why baptismal fonts and baptistries are constructed in an octagonal shape and why you might have octagonal patterns on a sanctuary floors.)

The harmony and symmetry of the heavenly order can be expressed numerically. For example, because of the seven days of creation in Genesis there are seven days in the week (corresponding also to a half phase of the idealised lunar cycle). The Sunday mass is the summit of the weekly cycle. In the weekly cycle there is in addition day, the so-called eighth ‘day’ of creation, which symbolises the new order ushered in by the incarnation, passion, death and resurrection of Christ. Sunday the day of his resurrection, is simultaneously the eighth and first day of the week (source and summit). Eight, expressed as ‘7 + 1’ is a strong governing factor in the Church’s earthly liturgy. (It is why baptismal fonts and baptistries are constructed in an octagonal shape and why you might have octagonal patterns on a sanctuary floors.)

Without Christ, the passage of time could be represented by a self enclosed weekly cycle sitting in a plane. The eighth day represents a vector shift at 90° to the plane of the circle that operates in combination with the first day of the new week. The result can be thought of as a helix. For every seven steps in the horizontal plane, there is one in the vertical. It demonstrates in earthly terms that a new dimension is accessed through each cycle of our participation temporal liturgical seven-day week.

The 7+1 form operates in the daily cycle of prayer in the Divine Office too. Quoting Psalm 118, St Benedict incorporates into his monastic rule the seven daily Offices of Lauds, Prime, Tierce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline; plus an eighth, the night or early-morning Office, Matins.

The 7+1 form operates in the daily cycle of prayer in the Divine Office too. Quoting Psalm 118, St Benedict incorporates into his monastic rule the seven daily Offices of Lauds, Prime, Tierce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline; plus an eighth, the night or early-morning Office, Matins.

Prime has since been abolished in the Roman Rite, but usually the 7+1 repetition is maintained by having daily Mass (not common in St Benedict’s time). Eight appears in the liturgy also in the octaves, the eight-day observances, for example of Easter. Easter is the event that causes the equivalent vector shift, much magnified, in the annual cycle. The Easter Octave is eight solemnities – eight consecutive eighth days that starts with Easter Sunday and finishes the following Sunday.

These three helical paths run concurrently, the daily helix sitting on the broader weekly helix which sits on the yet broader annual helix. We are riding on a roller coaster triple corkscrewing its way to heaven. This, however, is a roller coaster that engenders peace.

For those who are not aware of this, more information on this topic and how to conform you're life to this pattern, read The Little Oratory; A Beginner's Guide to Prayer in the Home and especially the section, A Beautiful Pattern of Prayer.

Pictures: The baptismal font, top, is 11th century, from Magdeburg cathedral. The floor patterns are from the cathedral at Monreale, in Sicily and from the 12th century. The building is the 13th century octagonal baptistry in Cremona, Italy.

How to Make an Icon Corner

Beauty calls us to itself and then beyond, to the source of all beauty, God. God's creation is beautiful, and God made us to apprehend it so that we might see Him through it. The choice of images for our prayer, therefore, is important. Beautiful sacred imagery not only aids the process of prayer, but what we pray with influences profoundly our taste: praying with beautiful sacred art is the most powerful education in beauty that there is. In the end this is how we shape our culture, especially so when this is rooted in family prayer. The icon corner will help us to do that. I am using icon here in the broadest sense of the term, referring to a sacred image that depicts the likeness of the person portrayed. So one could as easily choose Byzantine, gothic or even baroque styles.

The contemplation of sacred imagery is rooted in man’s nature. This was made clear by the 7th Ecumenical Council, at Nicea. Through the veneration icons, our imagination takes us to the person depicted. The veneration of icons, therefore, is an aid to prayer first and it serves to stimulate and purify the imagination. This is discussed in the writings of Theodore the Studite (759-826AD), who was one of the main theologians who contributed to the resolution of the iconoclastic controversy.

Beauty calls us to itself and then beyond, to the source of all beauty, God. God's creation is beautiful, and God made us to apprehend it so that we might see Him through it. The choice of images for our prayer, therefore, is important. Beautiful sacred imagery not only aids the process of prayer, but what we pray with influences profoundly our taste: praying with beautiful sacred art is the most powerful education in beauty that there is. In the end this is how we shape our culture, especially so when this is rooted in family prayer. The icon corner will help us to do that. I am using icon here in the broadest sense of the term, referring to a sacred image that depicts the likeness of the person portrayed. So one could as easily choose Byzantine, gothic or even baroque styles.

The contemplation of sacred imagery is rooted in man’s nature. This was made clear by the 7th Ecumenical Council, at Nicea. Through the veneration icons, our imagination takes us to the person depicted. The veneration of icons, therefore, is an aid to prayer first and it serves to stimulate and purify the imagination. This is discussed in the writings of Theodore the Studite (759-826AD), who was one of the main theologians who contributed to the resolution of the iconoclastic controversy.

In emphasising the importance of praying with sacred images Theodore said: “Imprint Christ…onto your heart, where he [already] dwells; whether you read a book about him, or behold him in an image, may he inspire your thoughts, as you come to know him twofold through the twofold experience of your senses. Thus you will see with your eyes what you have learned through the words you have heard. He who in this way hears and sees will fill his entire being with the praise of God.” [quoted by Cardinal Schonborn, p232, God’s Human Face, pub. Ignatius.]

It is good, therefore for us to develop the habit of praying with visual imagery and this can start at home. The tradition is to have a corner in which images are placed. This image or icon corner is the place to which we turn, when we pray. When this is done at home it will help bind the family in common prayer.

![]() Accordingly, the Catechism of the Catholic Church recommends that we consider appropriate places for personal prayer: ‘For personal prayer this can be a prayer corner with the sacred scriptures and icons, in order to be there, in secret, before our Father. In a Christian family kind of little oratory fosters prayer in common.’(CCC, 2691)

Accordingly, the Catechism of the Catholic Church recommends that we consider appropriate places for personal prayer: ‘For personal prayer this can be a prayer corner with the sacred scriptures and icons, in order to be there, in secret, before our Father. In a Christian family kind of little oratory fosters prayer in common.’(CCC, 2691)

I would go further and suggest that if the father leads the prayer, acting as head of the domestic church, as Christ is head of the Church, which is His mystical body, it will help to re-establish a true sense of fatherhood and masculinity. It might also, I suggest, encourage also vocations to the priesthood.

The placement should be so that the person praying is facing east. The sun rises in the east. Our praying towards the east symbolizes our expectation of the coming of the Son, symbolized by the rising sun. This is why churches are traditionally ‘oriented’ towards the orient, the east. To reinforce this symbolism, it is appropriate to light candles at times of prayer. The tradition is to mark this direction with a cross. It is important that the cross is not empty, but that Christ is on it. in the corner there should be representation of both the suffering Christ and Christ in glory.

‘At the core of the icon corner are the images of the Christ suffering on the cross, Christ in glory and the Mother of God. An excellent example of an image of Christ in glory which is in the Western tradition and appropriate to the family is the Sacred Heart (the one from Thomas More College's chapel, in New Hampshire, is shown). From this core imagery, there can be additions that change to reflect the seasons and feast days. This way it becomes a timepiece that reflects the cycles of sacred time. The “instruments” of daily prayer should be available: the Sacred Scriptures, the Psalter, or other prayer books that one might need, a rosary for example.

This harmony of prayer, love and beauty is bound up in the family. And the link between family (the basic building block upon which our society is built) and the culture is similarly profound. Just as beautiful sacred art nourishes the prayer that binds families together in love, to each other and to God; so the families that pray well will naturally seek or even create art (and by extension all aspects of the culture) that is in accord with that prayer. The family is the basis of culture.

Confucius said: ‘If there is harmony in the heart, there will be harmony in the family. If there is harmony in the family, there will be harmony in the nation. If there is harmony in the nation, there will be harmony in the world.’ What Confucius did not know is that the basis of that harmony is prayer modelled on Christ, who is perfect beauty and perfect love. That prayer is the liturgical prayer of the Church.

A 19th century painting of a Russian icon corner

The Dynamic of Prayer with Baroque Sacred Art - Why the Style of the Painting Makes You Pray Well

And how it is connected with the rosary. Have you ever had the experience of walking into an art gallery and being struck by a wonderful painting on the far side of the room. You are so captivated by it that you want to get closer. As you approach it, something strange happens. The image goes out of focus and dissolves into a mass of broad brushstrokes and unity of the image is lost. Then, in order to get a unified picture of the whole you have to recede again. The painting is likely to be an Old Master produced in the style of the 17th-century baroque, perhaps a Velazquez, or a Ribera, or perhaps later artists who retained this stylistic effect, such as John Singer Sargent. I recently made a trip to the art museum at Worcester, Massachusetts and there was a portrait by Sargent there that was about 12ft high and forced us back maybe 35ft so that we could view the whole.

This is a deliberately contrived effect of baroque painting. These paintings are created to have optimum impact at a distance. It is sad that the art gallery is the most likely place for us to find any art, let alone any sacred art that conforms to its principles. The stylistic elements of the baroque relate to its role firstly as a liturgical art form in the Counter-Reformation. The baroque of the 17th century is also the last style historically that Benedict XVI cites as an authentic liturgical tradition - where there is a full integration of theology and form - It should be of no surprise that this has an impact upon prayer.

The best analysis of the stylistic features of the baroque of the 17th century that I have seen is in a book about Velazquez, published in 1906 and written by RAM Stevenson (the brother of Robert Louis). RAM Stevenson trained as a painter in the same studio in Paris as John Singer Sargent. This studio, run by a man called Carolos Duran was unusual in the 19th century in that it did not conform to the sentimental academic art of the time (such as we might have seen in Bougeureau, whose painting is shown above), but sought to mimic the style the great artists of the 17th century, such as Velazquez. In this he says: “A canvas should express a human outlook on the world and so it should represent an area possible to the attention; that is, it should subtend an angle of vision confined to certain natural limits of expansion.[1] ” In other words we need to stand far enough away from the painting so that the eye can take it in as a single impression. Traditionally (following on from Leonardo) this is taken to be a point three times longer than the greatest dimension of the painting. This ratio of 3:1 is in fact an angle of 18°, slightly larger than the natural angle of focused vision of the eye, which is about 15°. When you stand this distance away, the whole painting can be taken in comfortably, without forcing the eye to move backwards and forwards over it to any extent that is uncomfortable.

If the intention is to appear sharp and in focus at a distance of three times the length of the canvas, it must be much painted as much softer and blurred on the canvas itself. In practice this means that when one approaches a canvas, the brush stroke is often broader than one first expected. So that if we do examine a painting close too, it is often hard to discern anything, it almost looks like a collection of random brush strokes. The whole thing only comes together and knits into an image once we retreat again far enough to be able to see it as a unified image. This property makes baroque art particularly suitable for paintings that are intended to have an impact at a distance. The scene jumps out at us.

If the intention is to appear sharp and in focus at a distance of three times the length of the canvas, it must be much painted as much softer and blurred on the canvas itself. In practice this means that when one approaches a canvas, the brush stroke is often broader than one first expected. So that if we do examine a painting close too, it is often hard to discern anything, it almost looks like a collection of random brush strokes. The whole thing only comes together and knits into an image once we retreat again far enough to be able to see it as a unified image. This property makes baroque art particularly suitable for paintings that are intended to have an impact at a distance. The scene jumps out at us.

There is an additional optical device that contributes to this. The composition of the painting is such that the figures are painted in the foreground. Two things: the placement of the horizon; and the relationship between the angle of vision of the perimeter of the canvas and that angle which spans each figure within, affect the sense of whether the image is in the foreground, middle ground or background in relation to the observer. Baroque art tends to portray the key figures in the foreground. When these two effects are combined the effect is powerful.

If we look consider the very famous painting of Christ on the cross by Velazquez, for example. Its appearance at a distance is of a perfectly modeled figure. As we approach we see that much of the detail is painted with a very loose, broad brush. I have picked out the loin cloth and face as detail examples. The artist achieves this effect is achieved by retreating from the canvas, viewing the subject at a distance and then walking forward to paint the canvas from memory. Then after making the brushstroke the artist returns to review the work from the position from which he intends the viewer to see it several feet back. I learnt this technique when I studied portrait painting in Florence. I was on my feet, walking backwards and forwards for two three-hour sessions a day (punctuated by cappuccino breaks, of course). Over the course of an academic year I lost several pounds! I was told, though I haven’t been able to confirm the truth of it, that Velazquez did not feel inclined to do all that walking, so had a set of brushes made that had 10ft handles.

This dynamic between the viewer and the painting is consistent with the idea of baroque art which is to make God and his saints present to us here, in this fallen world. There may be evil and suffering, but God is here for us. Hope in Christ transcends all human suffering. The image says, so to speak, ‘you stay where you are – I am coming to you. I am with you, supporting you in your suffering, here and now’. The stylistic language of light and dark in baroque painting supports this also. The deep cast shadow represents evil and suffering, but it is always contrasted with strong light, representing the Light that ‘overcomes the darkness’.

This dynamic between the viewer and the painting is consistent with the idea of baroque art which is to make God and his saints present to us here, in this fallen world. There may be evil and suffering, but God is here for us. Hope in Christ transcends all human suffering. The image says, so to speak, ‘you stay where you are – I am coming to you. I am with you, supporting you in your suffering, here and now’. The stylistic language of light and dark in baroque painting supports this also. The deep cast shadow represents evil and suffering, but it is always contrasted with strong light, representing the Light that ‘overcomes the darkness’.

This is different to the effect of the two other Catholic liturgical traditions as described by Pope Benedict XVI, the gothic and the iconographic. These place the figures compositionally always in the middle ground or distance, and so they always pull you in towards them. As you approach them they reveal more detail. (See a previous article on written for the New Liturgical Movement on the form of icons for more the reasons for this).

In this respect these traditions are complementary, rather than in opposition to each other. It has since struck me that the mysteries of the rosary describe this complementary dynamic also. They seem to describe an oscillating passage from earth to heaven and back again that helps us understand that God is simultaneously his calling us from Heaven to join him, but He is also with us here and helping to carry us up there, so to speak. If we consider the glorious mysteries, for example: first Christ is resurrected from the dead and then he ascends to heaven. Then He sends the Holy Spirit from heaven to be with us. Then we consider how Our Lady followed him, in her Assumption, and she and all the saints are in glory praying for us to join them. Both dynamics take place at the Mass itself. Christ comes down to us and is really present in Blessed Sacrament. As we participate in the Eucharist, we are raised up to Him supernaturally and then through Him and in the Spirit to the Father.

[1] RAM Stevenson, The Art of Velazquez, p30.

New Setting for the Creed from Corpus Christi Watershed

Here is a new chant setting for the Creed composed by Jeff Ostrowski, who happens to be president of Corpus Christi Watershed. He has published a recording and scores, all available for download free on their website, here. He has also written a brief account of his approach to composition. My belief is that we will not see chant coming to the fore again until we see more composition of new material, for English and Latin, OF and EF. This is what will connect with the uninitiated and open the way to the full tradition. Also, it is important that as much as possible is freely available, because it creates a dynamic environment where people hear things and have a go themselves, both performing and composing. From this we will start to see something powerful emerging. I have just forwarded it to our choir director to see if he wants to make use of it. The proof of its value will be in the singing - do we find that the congregations respond?

There is one other point. When sung in a church with a good acoustic, part of the beauty of chant, I feel, is the combination of the melody with the harmonics produced by the resonance in the building. It accentuates the implied harmonies of the intervals in a beautiful way. It is so subtle that I always think of it as gently leading my imagination to harmonies in heaven and I think of the angel hosts singing the heavenly liturgy with us.

So many churches today do not have a good acoustic and so the chant will sound flat in comparison. In order to support the singers, sometimes the organ is played with chant. I understand from organists that this is a real skill in itself, but even when done well, the harmonies never match those that I sense from natural resonance. It always seems a little disappointing. However, my experience is that for some reason, a drone underneath - a very simple organum, not parallel fifths or fourths - seems to add to the beauty of chant much more powerfully than an organ accompaniment and lead the imagination in the same way, even when the acoustic is not good. It seems to bring it to life. Furthermore, my experience is that congregations always enjoy it and remark on it afterwards.

So, Jeff, please give us a drone to sing underneath! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4gCJiK8MoYg