Contemporary orchestral pieces in the tradition of English Romanticism - think The Lark Ascending of Vaughan Williams or the music of Delius or Elgar.

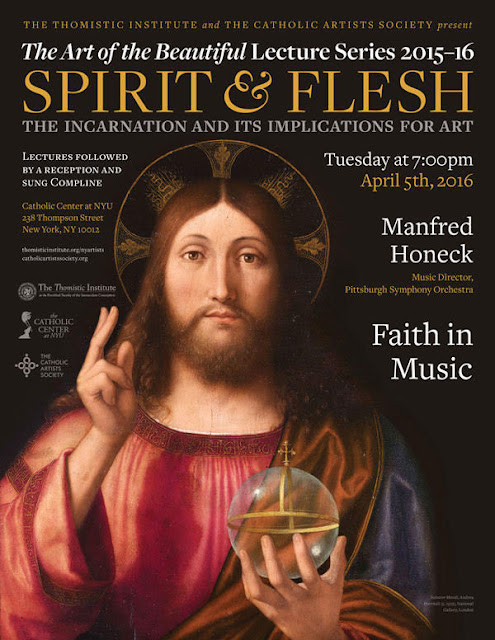

International Conductor to Address Catholic Artists' Society in NYC

Born in Austria, Honeck has worked to great acclaim with the world’s leading orchestras including the Berlin Philharmonic, Vienna Philharmonic and the London Symphony Orchestra, . In the United States, Honeck has conducted the New York Philharmonic (with whom he is appearing next week), The Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra and Boston Symphony Orchestra.

His talk is entitled "Faith in Music." A reception and sung Compline will follow.

A Wonderful Piece of Music by Brahms

I have been doing a regular series of pieces of music that have moved me with their beauty. The first was Schubert's Impromptus, the last one was about the rock band Genesis. In each case I had a long story to tell about the impact it had on my. In this case, I have no story tell other than the fact that I have always enjoyed it. It is Brahm's String Sextet No 1.

When I first had an interest in classical music in my early 20s I always thought of chamber music as a scratchy sounding and inferior version of orchestral music. In time I came to enjoy it more and more. The separate voices are much more discernible that in orchestral music, I find. Also, because it is a lot cheaper to put on, it is possible to small intimate concerts in small halls (London's Wigmore Hall was a favourite of mine) where it is possible for me to afford seats close to the performers. I began to enjoy chamber music live particularly as a result. I saw a wonderful performance of this Brahms piece at St John's church in Smith Square, Westminster about 10 years ago.

I have been doing a regular series of pieces of music that have moved me with their beauty. The first was Schubert's Impromptus, the last one was about the rock band Genesis. In each case I had a long story to tell about the impact it had on my. In this case, I have no story tell other than the fact that I have always enjoyed it. It is Brahm's String Sextet No 1.

When I first had an interest in classical music in my early 20s I always thought of chamber music as a scratchy sounding and inferior version of orchestral music. In time I came to enjoy it more and more. The separate voices are much more discernible that in orchestral music, I find. Also, because it is a lot cheaper to put on, it is possible to small intimate concerts in small halls (London's Wigmore Hall was a favourite of mine) where it is possible for me to afford seats close to the performers. I began to enjoy chamber music live particularly as a result. I saw a wonderful performance of this Brahms piece at St John's church in Smith Square, Westminster about 10 years ago.

My introduction to it was a recording of a piano transcription of the second movement made by Brahms himself, I am not aware that he did the same for the rest of the sextet, so presumably he was particularly attached to this movement. The recording I heard was by Emanuel Ax. I couldn't find it on YouTube so here is a recording by Idel Biret, the Turkish pianist who is known for her interpretations of the Romantic repertoire and Brahms especially.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dQbI7uI6mJc

Here is a recording of the same piece with six stringed instruments.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h1AZ8FmIWcI

How to Compose Psalm Tones for the Vernacular - Have a Go Yourself

Here's an article that I wrote and was first posted on the traditional music website, Corpus Christi Watershed. It is about the principles used when creating psalm tones for the vernacular. It explains the method by which the tones that are given on this site were developed at Thomas More College and how we tried to incorporate the principles of tradition when adapting tones from the old English Sarum Rite written originally for the Latin to the English. Read the full article here.

I always maintain that to be vital, every tradition must always have new forms that encapsulate its essential elements, but speak anew to each successive generation. This means that we cannot simply look at the past in regard to sacred music. We must also compose. If we don't the tradition will die again. So, in accord with that I say if you don't like what I have done then please think about creating something that you do like!

Here's an article that I wrote and was first posted on the traditional music website, Corpus Christi Watershed. It is about the principles used when creating psalm tones for the vernacular. It explains the method by which the tones that are given on this site were developed at Thomas More College and how we tried to incorporate the principles of tradition when adapting tones from the old English Sarum Rite written originally for the Latin to the English. Read the full article here.

I always maintain that to be vital, every tradition must always have new forms that encapsulate its essential elements, but speak anew to each successive generation. This means that we cannot simply look at the past in regard to sacred music. We must also compose. If we don't the tradition will die again. So, in accord with that I say if you don't like what I have done then please think about creating something that you do like!

The painting, by the way, is from 1808 by the French artist Granet of the choir singing in the Capuchin church in Rome.

Genesis - Can Popular Culture Can Create the Desire for God? I Say Yes!

This is about pop music, not scripture! Here is another in a series of occasional articles that discuss music that has move me greatly by its beauty. This one is a little more risky than the others. I'm going to talk about the rock band Genesis in their early manifestation (when Peter Gabriel was their lead singer and Phil Collins played drums and nothing else). There's nothing worse that an old codger trying to convince you that the pop music he liked in his day was genuinely good music. When I was young I used to yawn when the generation above me used to complain about my music and then tell me how great the Sixties was.....This is almost going to be one of those articles, but bear with me, I do have a reasonable point to make. So even you don't have a clue who I'm talking about, there might be something in it for you by the end!When I was sixteen, I had no interest in music and if you'd asked me I would have said that I just wasn't musical. Then I heard the album (do we still use that word nowadays?) by Genesis called Selling England by the Pound. This was my first experience of hearing a piece of music that just transported me through its beauty (the instrumental section in the last half of the track called Cinema Show and then instrumental sections, again, on the track, the Firth of Fifth ). What would happen later with Schubert, Brahms, Mozart and Palestrina happened first with Genesis.

This is about pop music, not scripture! Here is another in a series of occasional articles that discuss music that has move me greatly by its beauty. This one is a little more risky than the others. I'm going to talk about the rock band Genesis in their early manifestation (when Peter Gabriel was their lead singer and Phil Collins played drums and nothing else). There's nothing worse that an old codger trying to convince you that the pop music he liked in his day was genuinely good music. When I was young I used to yawn when the generation above me used to complain about my music and then tell me how great the Sixties was.....This is almost going to be one of those articles, but bear with me, I do have a reasonable point to make. So even you don't have a clue who I'm talking about, there might be something in it for you by the end!When I was sixteen, I had no interest in music and if you'd asked me I would have said that I just wasn't musical. Then I heard the album (do we still use that word nowadays?) by Genesis called Selling England by the Pound. This was my first experience of hearing a piece of music that just transported me through its beauty (the instrumental section in the last half of the track called Cinema Show and then instrumental sections, again, on the track, the Firth of Fifth ). What would happen later with Schubert, Brahms, Mozart and Palestrina happened first with Genesis.

It was purely the music. I didn't really understand the lyrics and didn't really care. The words sounded intellectual - the references were both obscure and eclectic enough to convince me that there was something clever going on and this satisfied my teenage pride. What I did pick up created a fantasy world that was evocative of rural idylls and classical mythology and this did seem to suit the music. For example there were references to classical literature and Dante with figures such as 'old father Tiresius' although I don't know why, and fantastic stories about Victorian explorers bringing the man-eating giant hogweed to Britain from Russia. Later, I heard the keyboardist Tony Banks explain that the reason they went in for this sort of thing was that they had all met at an English all-boys public school, Charterhouse, and they were still so young that none of them had really had many girlfriends. Because of this they didn't feel confident writing about girls in their songs like all the other pop stars did. Reinforcing this were the photographs I saw of them on stage. Lots of smoke, costumes and bright lights. Peter Gabriel in particular looked slightly wierd, but I liked that.

As a result of my experience in listening to this album, I became very interested in music and energetically started to collect all of their music and search for other groups that seemed to be similar. I listened to groups Yes, King Crimson, Emerson Lake and Palmer, if these mean anything to anyone any more.? Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin were there too, and I know that these names are still around today. All seemed good and I bought the albums, listened to the music and talked seriously about the personnel changes in the bands with my friends; but none seemed to have the quality of this early Genesis music which had connected with me so strongly. I didn't experience such a strong reaction to a piece of music again until I heard Schubert's Impromptus five years later that I had a similar reaction. (You can read about that occasion in an earlier article Schubert Soothes Savage Beasts and Placates Food Throwing Students.)

So why am I writing about this? Many years later I heard an interview with members of the band and they talked about how they composed the music. Unlike every rock band they knew about, they refused to use the blues scale and used conventional classical scales and musical forms in what they did. They used rock instruments, and had complex rhythms in it, with Phil Collins a virtuoso drummer interpreting their music. I didn't know it at the time, but this is what I was picking up in their music and responding to. This is why it sounded different.

I always think that music connects with the soul and then gives it motion. That motion can be towards something higher, or something lower. If it is sending me towards something higher, then it is stimulating in me, at some level, a desire for the ultimate beauty, God. This music connected with me as sixteen year old and created a desire for more. I don't think that classical music would have done it then. I had to listen to lots of Genesis before I was ready for that, but it sent me in the right direction. I wasn't thinking of God, but I was searching for beauty. I listed the other music names that had such an effect on me above and that final one, Palestrina, I heard in the Brompton Oratory over 10 years later during Mass. After Palestrina it seemed, the only way up was God and he was preparing me to see that. If you pushed me now I might say that Byrd's Ave Verum Corpus sits between Palestrina and God, but I don't want to split hairs.

What Genesis had done was create a style of popular culture that participated in the traditional forms of beauty. They were good composers and musicians but (and time may judge otherwise) probably not at the level of those other figures. They were not, to my knowledge Christian, but they were doing what Christians who wished to engage with modern culture ought to have been doing. That is, create forms that participate in the timeless values that unite all that is good, and then present in such as way that connect with the people of the day and open their hearts, subtly, to God. Popular culture changes so much and so quickly that I wouldn't expect Genesis to connect with people today in the same way. it is the exact opposite of the way that most Christians attempt to harness popular culture - they use the degraded forms of the pop culture and then add overtly Christian lyrics. The result, Christian rock, is just a bad advert for the Faith.

We need more composers who can do the same thing today - create a Christian popular culture that hooks people subtly through form. It would not sound like Genesis now I don't think. It almost certainly just sounds dated to most people who listen to today's pop music, but the same principle could apply if someone knew how to do it.

The other point is that Genesis, Peter Gabriel, Phil Collins were a success in their field by any measure. I would maintain that harnessing beauty in the arts offers those artists who do it well a greater chance of popular success than if they just go along with the herd.

Anyway, so back to being a grumpy old man...here's real music not like the stuff that the youth of today listen to....

The Firth of Fifth http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SD5engyVXe0

Cinema Show: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G501Ii0X0NE

Below Genesis circa 1972.....

Thomas More College Choir Sings for the Extraordinary Form, First Sunday of Lent

Here are some recordings of what we sang. Last Sunday, the First Sunday in Lent, the Thomas More College choir sang at St Patrick's in Nashua, NH. We sang at the invitation of Fr Kerper, the pastor at St Patricks. The college has enjoyed a long connection with the parish, its longest standing chaplain, Fr Healey, is resident at the church. The Mass was composed by a German, Blasius Amon, in the 16th century - Missa Super 'Pour ung Plaisir'. Our director, Dr Thomas Larson, did his usual and put his cell down amongst us in the choir stall and came up with these recordings.

I had never heard of Blasius Amon before Tom introduced this to the choir, but it is a great Mass for a choir to learn polphony on. Relatively simple, but still very good to listen to. I hope these recordings give a sense of it. As usual, remember this is an amateur choir recorded on a very simple piece of equipment. Below are the Sanctus, Benedictus and Agnus Dei from the Mass.

Here are some recordings of what we sang. Last Sunday, the First Sunday in Lent, the Thomas More College choir sang at St Patrick's in Nashua, NH. We sang at the invitation of Fr Kerper, the pastor at St Patricks. The college has enjoyed a long connection with the parish, its longest standing chaplain, Fr Healey, is resident at the church. The Mass was composed by a German, Blasius Amon, in the 16th century - Missa Super 'Pour ung Plaisir'. Our director, Dr Thomas Larson, did his usual and put his cell down amongst us in the choir stall and came up with these recordings.

I had never heard of Blasius Amon before Tom introduced this to the choir, but it is a great Mass for a choir to learn polphony on. Relatively simple, but still very good to listen to. I hope these recordings give a sense of it. As usual, remember this is an amateur choir recorded on a very simple piece of equipment. Below are the Sanctus, Benedictus and Agnus Dei from the Mass.

I would draw your attention also to the Communion antiphon and psalm mediation. The antiphon is in the traditional plainchant, in mode III, as proscribed. The psalm is sung to the harmonised mode III tone composed by myself and harmonised by our Composer-in-Residence, Paul Jernberg.

For the offertory mediation we sang the Stabat Mater Dolorosa. I don't have a recording of this, but we based what we did on a You Tube video I found of some Norwegian monks singing it and so I reproduce that for you. They have altered the rhythm slighly, as those who know it will hear immediately. Also, they have a gentle organum (drone) going on underneath. Tom and I listened to this and Tom recognised that at various points they had not just one, but two organum drones going on (very subtly applied). So this is how we sang it. We sang the first verse in unison, in the second with the tenors and some altos singing an organum note corresponding to the very first note of the melody. The third we introduced in additional bass organum drone on a note a fourth lower. Then we started the cycle again. This has a powerfully contemplative effect.

We very much hope that we might be asked back in the future!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=muJccdJJrwk

Bill Nelson and Be Bop Deluxe

I have not met a mother yet who does not think that her baby is the most beautiful baby there is. When I first heard a mother saying it, I thought perhaps there was some element of irony. All babies are beautiful, I thought, but you don't really believe that yours is the most beautiful do you? I once aired these doubts. I laughed and said to the mother that every mother I had met thought that. Yes, she replied in absolute seriousness, without even a trace of irony: 'Except that my baby really is the most beautiful.' This is how the eyes of love see the beloved. I imagine this might give us insight into how God sees every single one of us. The mother is not blinded by love. Just the opposite - the scales have fallen off her eyes so that she sees the true value of that one small person. It may exist, but I have never seen the same level of devotion from fathers. In men this natural instinct seems to be misdirected and applied to more superficial things. I have seen devotion to fourth rank professional soccer team, Tranmere Rovers (who at this time in the early Eighties were averaging gates of 800 people) so great that when I asked him to explain why his beloved team was languishing at the foot of the table he replied in all seriousness, again no irony whatsoever, that it was all down to a complete season of 'bad refereeing'...nevertheless he was convinced that this wouldn't contintue, that the future held hope and tipped them for promotion the following season. This, I suggest, is blind devotion.

On a similar level of superficiality, guys have a blindness to the awfulness of the rock or pop music they grew up with. There is nothing worse than listening to somebody else's greatest hits collection on their iPod; and nothing better than listening to your own. Especially when its a 50 year old man and everything dates from the strictly delineated time period of 1973-1988, after which time all pop music 'went downhill' so demonstrating that the youth of today listen to tuneless, raucous, inane rubbish barely meriting the categorization of music (so different to what we used to listen to). After 1988 this typical man started to branch out into jazz and classical and maybe now listens to chant and polyphony. But he still won't let go of all of the rock music he grew up with, and is convinced that it has genuine artistic merit.

I might say that this hypothetical example described above applied to me...except that the music I have downloaded onto my iShuffle really is the best from a golden age of popular culture when there was genuine musicianship and that everybody should be able to appreciate it!

And to prove it here is a video of the singer/songwriter from one of my favourite groups from the late 1970s, Bill Nelson whose group was Be Bop Deluxe. When I was surfing around the net one day, I was amazed to come across this old interview with him in which he does describe the process of inspiration as something that comes from God. This is all I need, I thought, reference to God will justify its inclusion in this blog....

Joking aside, regardless of what you think of my taste for out-of-date pop music (which is probably slightly worse than I think it is), I would love to see a new popular music appear as part of the New Evangelisation. It is an assumption of many people today that what sells appeals to the lowest common denominator and can never raise people's souls to God. I do not agree. However, the answer is not, repeat not, Christian rock as we hear it today (which is just a pale version of the forms) which no self-respecting rock fan would every really listen to. Rather, it is up to Christians to find music that is entertaining and accessible, that is powerful and beautiful. If what is good appeals to something that is ordered in us, it will always have a greater appeal than that which appeals to what is disordered in us. This will involve consideration of harmonic forms as well as the words and might well include also modern developments in rhythm and electrical manipulation of sound. Just like any aspect of the culture, provided it is employed discerningly it can be transformed into something good.

I do not know what such music will sound like. While I think it is unlikely that it could convert, it can begin to open the door to something better. The groups that I gravitated to when I was listening, I found out afterwards, were often those who avoided the rock'n'roll blues scales and harmonies, and used more conventional harmony and counterpoint. It may be a surprise to some that such groups did exist and I know of one or two trying to do this now. George Sarah in California is one. This stimulated a desire for something more that took me to classical music and ultimately liturgical.

So for any whose interest persists, here is some music by the 'fastest guitarist in Wakefield' Bill Nelson. Some from their heyday in the Seventies and a recent recording of him playing the 1975 song Maid in Heaven, now 63 and still very sharp and clear in voice and instrumental technique. The first one is the interview of him after this in the 1980s when he became more art-house in his approach. In regard to this it is interesting that even in guitar playing he describes how important, just as in the training of painting, the imitation of great masters was in helping him to learn (in this case the Old Masters were his boyhood guitar heroes!)

Creativity and Fun with Substance

Dudley Moore parodying Beethoven piano sonato and Schuber lieder ('Die Flabberghast') I saw the first video below on Damien Thompson's blog on The Daily Telegraph website. It is Dudley Moore playing his own composition, a parody of a Beethoven piano sonato based on the melody of Colonel Bogey (or if you prefer the tune from the Bridge Over the River Kwai). It is recorded in the Sixties. I have spoken about how important creativity within a tradition is for keeping it alive and opening the door that leads to the timeless principles that are at its core for modern audiences. In the context of sacred music, I described this a need for composers whose work has the quality of noble accessibility, see here.

This is not sacred music, but it is just the sort of creativity that will open the door to the real thing, drawing people in through more than just he music. I find it brilliantly funny.

Moore was organ scholar at Magdalen College, Oxford. After university he achieved national prominence as jazz pianist and then as part of the Beyond the Fringe comedy quartet with Alan Bennet, Jonathan Miller and Peter Cook. Jonathan Miller, who went on to become a famous opera director (among other things) is the figure opening the piano lid for him before he performs. Alan Bennet and Peter Cook especially also became household names in Britain. Bennet is a playwright and Cook a comedian with whom Moore eventually formed a famous duo.

All were at Oxford University. This creativity is encouraged by the form of education that exists at Oxford and in form (if not so much in substance any more) is based upon the medieval university. I am always amazed that more educational institutions do not copy this given the success of the two universities, Oxford and Cambridge, that bear the mark of the medieval university today. All those in continental Europe were destroyed by Napoleon and re founded on a different organisational model. American universities and colleges, even the Catholic ones, are almost all based upon this later, German model. I have written about this here.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GazlqD4mLvw

Here is another video, this time Moore's parody of a Schubert Lieder 'Die Flabberghast'

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=idBZPteNJxs&feature=related

The Music of Roman Hurko and the Principle of Noble Accessibility

• The noble accessibilty that needs to characterize all Catholic sacred music, is important both in congregational and choral music, each of which has an important place in the Liturgy.

• Whereas music composed for the congregation needs to be “singable”, music composed for choirs needs to be accessible to the minds and hearts of the congregation as they hear it! It needs to communicate in a musical language that the faithful can readily receive, and which through its beauty and sacred character lifts hearts to the transcendent.

• Yes, there might be some formation needed here, as those unaccustomed to the tradition of Sacred Music adjust to its contemplative nature. However, one should not be required to undergo extensive musical training in order to appreciate music in the Liturgy! The formation required will be more theological and spiritual, rather than musical.

• The choral music of Roman Hurko, composed for choirs singing the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom (Eastern Catholic Rite), is an eminent example of this noble accessibility in choral music. His melodies, harmonies and rhythms are composed in such a way as to communicate to the common man, a profound beauty that lifts the heart and mind to prayer.

• This aspect of listening as well as singing is important in the liturgy. Some settings or parts emphasize the vocal participation of the congregation; others, such as polyphonic settings in the Western tradition, call forth the more meditative participation of the congregation. Antiphonal singing, an important aspect of both Eastern and Western liturgical traditions, engages us in both ways. Sometimes this involves having the congregation divided into two groups, while at other times the antiphonal principle is manifested through the choir alternating with congregation. In the latter case, it is appropriate for the choir to sing more ornately beautiful and challenging settings, corresponding to their musical abilities, while the congregation sings simpler arrangements.'

As an artist I am always thinking about the parallels between sacred art and music. In the case of art participation is not a requirement - we don't expect everybody to be painting in church, that would be art therapy! But the other aspect of accessibility does apply. It is down to artists to work within the traditional forms in such a way that ordinary church goers will respond easily and willingly so that it raises their hearts and minds to God.

Roman Hurko's website is www.romanhurko.com; and a link through to his iTunes page, for anyone who would like to download his music, is here.

Paul Jernberg is Composer-in-Residence at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts, Merrimack, NH.

http://youtu.be/qdyGJUinKGE

Why Create New Art or Music When There's Plenty of Good Old Stuff Around?

For me a living tradition in art (and the argument would apply equally to music), is not simply one that preserves and hands on the great work past, it is one also that reapplies its core principles to create new art or music. But one might ask, why bother? With the standard of reproductions in art now, you could have a Fra Angelico in your church at a fraction of a cost of commissioning an original work of art. Similarly, there is so much chant and polyphony already composed, you could have something different but of the highest quality every Sunday for several lifetimes.

For me a living tradition in art (and the argument would apply equally to music), is not simply one that preserves and hands on the great work past, it is one also that reapplies its core principles to create new art or music. But one might ask, why bother? With the standard of reproductions in art now, you could have a Fra Angelico in your church at a fraction of a cost of commissioning an original work of art. Similarly, there is so much chant and polyphony already composed, you could have something different but of the highest quality every Sunday for several lifetimes.

Nevertheless, a living tradition will be one in which there are artists and composers who are constantly creating new work, without ever compromising on the core principles that define it. In doing so it will reflect and speak to its time and its place in a unique way. When the timeless and the time-bound aspects are in harmony, you have the most powerful effect. When this harmony is present it will appeal to most people. For many, I believe, it will stimulate into life that part that that can respond otentially to all other traditional forms. Once this is done then there is every chance that many who previously would have been unaffected by centuries old chant or polyphony will now respond. This is the special value of 'new traditional' art and music.If there is an imbalace in the timeless and time-bound aspects (or just a poor attempt at both), you risk creating pastiche on the one hand, or sentimental imitations of modern secular fashion on the other. Iconography demonstrates this perfectly. Aidan Hart, my teacher always says that those who understand iconography well can look at any icon without knowing anything about it, place to a particular geographical location and to a time period within 50-100 years. What is changing here is not the principles that define the tradition - these never waver; but how they are applied. This is how, for example, we can distinguish between Russian icons and Greek icons and within the Russian style Gregory Kroug and Andrei Rublev.

Nevertheless, a living tradition will be one in which there are artists and composers who are constantly creating new work, without ever compromising on the core principles that define it. In doing so it will reflect and speak to its time and its place in a unique way. When the timeless and the time-bound aspects are in harmony, you have the most powerful effect. When this harmony is present it will appeal to most people. For many, I believe, it will stimulate into life that part that that can respond otentially to all other traditional forms. Once this is done then there is every chance that many who previously would have been unaffected by centuries old chant or polyphony will now respond. This is the special value of 'new traditional' art and music.If there is an imbalace in the timeless and time-bound aspects (or just a poor attempt at both), you risk creating pastiche on the one hand, or sentimental imitations of modern secular fashion on the other. Iconography demonstrates this perfectly. Aidan Hart, my teacher always says that those who understand iconography well can look at any icon without knowing anything about it, place to a particular geographical location and to a time period within 50-100 years. What is changing here is not the principles that define the tradition - these never waver; but how they are applied. This is how, for example, we can distinguish between Russian icons and Greek icons and within the Russian style Gregory Kroug and Andrei Rublev.

Sometimes the modern expression is not something never seen before, but a re-emergence of an old style, that has its time again. Fra Angelico is an artist who seems to be liked a great deal at the moment, and so any artist who could capture the qualities of his art would do well I think. Having said this, however closely we follow a past form, that time-bound aspect will never be absent altogether. Each artist is a unique individual and even the most cloistered monk will susceptible to the culture of his day. This individual aspect of the work cannot be quashed altogether. The task for the artist, or composer, is to direct it so that it conforms to what is good, true and beautiful. To certain extent this will be an intuitive process but creativity is directed by conscious reason as well. When the artist is responding to a clearly defined need then this latter aspect comes into play particularly.

I think the music of composer Paul Jernberg does this. You can hear is music here. We have been collaborating in developing music for the liturgy of the hours at Thomas More College for the last year and we will be working together at the summer retreat at the college in August where the aim is to teach people how to sing it. What is so great about this is first, how appealing it is and second how easy it is to sing at a satisfying level. This is what the ideal of noble simplicity is all about.

I think the music of composer Paul Jernberg does this. You can hear is music here. We have been collaborating in developing music for the liturgy of the hours at Thomas More College for the last year and we will be working together at the summer retreat at the college in August where the aim is to teach people how to sing it. What is so great about this is first, how appealing it is and second how easy it is to sing at a satisfying level. This is what the ideal of noble simplicity is all about.

Here's another example. We had a priest who visited regularly and even if celebrating a novus ordo would always lead us in reciting the St Michael prayer after Mass. He used to turn to the tabernacle as he said it. I thought that it would be great if we had an image to focus on, so I painted one for the back wall. Then I then asked Paul if he could come up with an arrangement so that we could sing the prayer. Very quickly he adapted a traditional Byzantine tone to it. In this case there is minimal change musically, because he felt it didn't need it.

This arrangement has been very popular. The students have picked up on it and completely on their own instigation now sing it in four-parts harmony every night after Compline. Dr William Fahey has asked that we sing it after each Mass in response to the attacks on the Church in connection with the new healthcare legislation. Dr Tom Larson, who teaches the choir at the college is so enthusiastic about it that took this up to his men's group in Manchester, New Hampshire. Within 15 minutes they learnt it and enjoying it so much they decided to record it on a mobile phone. Next day it was up on YouTube, and this is what you see here. As you listen to it remember that this is a cell-phone recording of an amateur choir of 5 men of varying ability (including myself on bass - right at the bottom in more ways than one) singing it virtually unrehearsed.

Paul Jernerg has just been made Composer in Residence at Thomas More College. He will be composing music for us to showcase and visiting to give master classes in performance and for those who have the ability, composition. One of the things we have asked him to do is to compose a Vespers of St Michael the Archangel and I can't wait to hear it.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fwIoAzbo9wA&feature=youtu.be

The Logos of Sacred Music, by Paul Jernberg

A composer tells us his approach in composing works that are fresh and new, while reflecting the timeless principles that constitute sacred music. Listen also to his beautiful newly composed Mass.

The following is an essay written by the composer Paul Jernberg. Paul has composed his Mass of St Philip Neri for the new translation of the Mass. In the essay below he discusses the principles that guide him in composition and which enable him to compose new music in accordance with timeless principles. We have been singing his compositions at Thomas More College - I have been working with him in creating psalm tones for the vernacular that are modal and so sit within the tradition.This has enabled us to chant, for example, the traditional Latin proper for communion and then a communion meditation in English without any sense of disunity.

A composer tells us his approach in composing works that are fresh and new, while reflecting the timeless principles that constitute sacred music. Listen also to his beautiful newly composed Mass.

The following is an essay written by the composer Paul Jernberg. Paul has composed his Mass of St Philip Neri for the new translation of the Mass. In the essay below he discusses the principles that guide him in composition and which enable him to compose new music in accordance with timeless principles. We have been singing his compositions at Thomas More College - I have been working with him in creating psalm tones for the vernacular that are modal and so sit within the tradition.This has enabled us to chant, for example, the traditional Latin proper for communion and then a communion meditation in English without any sense of disunity.

What characterises both the compositions you can hear here and the music he has composed for us at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts is how simple it is to perform, yet how good it sounds. He really has hit that standard of noble simplicity - music that is so beautiful that you want to sing it, and so simple that you can. Furthermore, there is not even a hint of sentimentality in his music.

I have punctuated the text of his essay with links through to audio of the St Philip Neri Mass so that you can pause and listen as you read along. The attached audio files have been recorded by members of the Parish Choir of St. John's in Clinton, MA and of the Chorus of Trivium School, a Catholic high-school in Lancaster, MA (plus myself and Dr Tom Larson from Thomas More College of Liberal Arts and an additional member of Tom's amateur chant and polyphony choir, the Schuler Singers). Please bear in mind as you listen to them that they are not professional recordings and precisely because it is amateur singers that you are listening to it represents an endeavor to incarnate the ideal articulated in the essay on the Parish level:

The Logos of Sacred Music

An introduction to the Mass of Saint Philip Neri

The composition of this work has been my response to the need for a fitting musical setting of the Ordinary from the new English translation of the Roman Missal. In the creation of this music it has been my goal to fulfill three essential criteria, namely, that it have a true sacred character, that it be imbued with the qualities of authentic artistry, and that it possess a noble accessibility will allow it to be received into the hearts of ordinary people of good will throughout the English-speaking world.

Sacred Character

Music in the Liturgy of the Catholic Church should by its nature have a distinct identity that is contemplative, vibrant, and rooted in ancient tradition. In the perennial Catholic vision of the Liturgy, all of its sensible elements are intended to provide a sacred space that is worthy to welcome the sacramental Divine Presence. This intention would seem to surpass the reasonable scope of ordinary human creativity, as the finite aspires to welcome the infinite, the creature to create a worthy space for the Creator. And yet, both faith and aesthetic sensitivity perceive that an inspired tradition has indeed developed over the course of the centuries – including aspects such as architecture, visual arts, and music - which has fulfilled this task in a marvelous way.

In the West, this inspired musical tradition has as its foundation a vast repertoire commonly known as Gregorian Chant. Any composer who wishes to approach the task of composing music for the Roman Catholic Liturgy in a serious way, should thus be thoroughly versed in the study and performance of this repertoire, realizing the littleness of his own efforts in relation to the greatness of the tradition. The composer should also seek to understand and apply those musical principles of Gregorian Chant that have allowed it to serve its purpose so aptly. As expressed by the authors of the post-conciliar Church document, Musicam Sacram:

Musicians will enter on this new work with the desire to continue that tradition which has furnished the Church, in her divine worship, with a truly abundant heritage. Let them examine the works of the past, their types and characteristics, … so that “new forms may in some way grow organically from forms that already exist,” and the new work will form a new part in the musical heritage of the Church, not unworthy of its past.[1]

And furthermore:

Let them produce compositions which have the qualities proper to genuine sacred music, not confining themselves to works which can be sung only by large choirs, but providing also for the needs of small choirs and for the active participation of the entire assembly of the faithful.[2]

Along these same lines Pope Benedict XVI recently pointed out:

It is possible to modernize holy music, but this cannot happen outside the great traditional path of the past, of Gregorian chants and sacred polyphonic choral music… [3]

What are the “qualities proper to genuine sacred music” that need to be followed attentively in the composition and performance of new works? This is in fact a crucial question which requires much more space than the scope of this introduction would allow, in order to be answered adequately. However, a few first principles can be briefly articulated here:

- The human voice is always the primary instrument, and often the only instrument. Being an integral part of man, rather than his exterior creation, the voice has a unique capacity for intimate expression of the depth and breadth of human feeling and experience. It is equally accessible to all people and all cultures. When the organ or other instruments are used, it is for the purpose of supporting or enhancing, rather than dominating or supplanting, the voice.

- The rhythm of the music is united with the natural rhythm of the given sacred text, either through assuming the textual rhythm as its own, or by engaging in a gentle interplay with it. Any strong metrical or rhythmic effects that might overshadow the meaning of the text are avoided. With a few exceptions, Gregorian chant is characterized by a non-metered rhythm that allows great freedom in respecting the meaning and flow of the Word.

- Melodic lines and harmonies are carefully chosen to evoke dispositions and emotions that are appropriate to liturgical worship and interiority, and which steer clear of secular associations. This distinction is not meant in any way to demean the multifarious beauty that belongs to secular life and art, or to deny its transcendent dimension, but rather is meant to facilitate the flourishing of each - the sacred and the profane[4], divine worship and social intercourse - in its own proper time and place.

Authentic Artistry

It does not do justice to the nature of the Liturgy for its music to be merely correct, even according to the above-mentioned principles. In order for sacred music to reach its full stature, composers and musicians need to exercise true artistry, in which knowledge, inspiration, and skill all play a vital role.

Many may object here, saying that liturgical music is meant for “prayer rather than performance,” implying that prayer, being a humble, intimate communication with God, excludes or minimizes the need for artistry, which by its nature demands a focus on the externals of music-making. There is an element of truth in this, namely, that the relational dimension of the Liturgy is of immeasurably more importance than the artistic dimension. However, it is this very relational dimension which should motivate and empower composers and musicians as they devote all of their skill to create something as beautiful as possible for God, the Beloved. In addition, a certain level of artistry in composition and choral performance provides a foundation from which the other participants in the Liturgy can more fully interiorize the meaning of the words and more prayerfully join in the singing of their parts.

In the context of sacred music, compositional artistry will be manifested in gracefulness and dignity of melodic line, harmony, and dynamics, rather than in striking effects or grandiosity. The artistic performance of this music by cantors and choirs requires, among other things, diligent attention to precision of pitch and rhythm, natural resonance, lively and sensitive dynamics, appropriate tone quality, and clear diction. Qualities such as interiority and unity of sound among voices should preclude any harsh effects or displays of virtuosity, however appropriate these latter might be in other contexts.

Composers and performers of all kinds of music bear witness to the fact that the phenomenon of inspiration is a mysterious but important element in their creative process. How much more should the composer of sacred music, conscious of the dignity of the Liturgy, prayerfully seek that inspiration which will give his music a living, joyful, peaceful identity, beyond the mere notes on the musical score? When this gift is skillfully cultivated, choirs and congregations can in their turn participate in an experience of inspired beauty, which is directed toward the praise and glory of God.

Noble Accessibility

One of the clearest messages from the Second Vatican Council to composers of sacred music, was the need to create music that would facilitate the “full, conscious, and active” participation of the faithful:

In the restoration and promotion of the sacred liturgy, this full and active participation by all the people is the aim to be considered before all else, for it is the primary and indispensable source from which the faithful are to derive the true Christian spirit…[5]

How can music help to achieve this goal, while faithfully maintaining the other foundational qualities listed above? On the one hand, unceasing and genial efforts should be made to help priests and lay people to re-discover the great traditions of sacred music that are in fact their rightful patrimony. Too often this heritage has been ignored or rejected on the false premise that it is no longer relevant to modern man. On the other hand, the legitimate development of culture, as well as the authorized use of the vernacular in the Liturgy, beg for the conception of worthy new music to accompany both Latin and translated Liturgical texts. And in order for this music to fulfill its purpose, it needs to be imbued with a noble accessibility that allows it to be not only admired, but also deeply welcomed by “ordinary” people so as to become a fitting and authentic expression of their faith.

When this quest for full participation has been separated from the need for true sacred character and authentic artistry in liturgical music, as has often been the case over the decades since Vatican II, the results have been deeply disturbing for those sensitive to the musical, psychological and spiritual dimensions of the Mass. As world-renowned maestro Riccardo Muti recently observed:

The history of great music was determined by what the Church did. When I go to church and I hear four strums of a guitar or choruses of senseless, insipid words, I think it's an insult… I can't work out how come once upon a time there were Mozart and Bach and now we have little sing-songs. This is a lack of respect for people's intelligence. [6]

This interview, in which Muti praised the efforts of Pope Benedict to promote a renewal of sacred music, was a tremendous encouragement to me in my composition of the Mass of St. Philip Neri. He speaks authoritatively on behalf of all great musicians and all devout Catholics when he pleads for the renewal of sacred music in the Church’s Liturgy. At the same time he understands the need for accessibility:

Rather than obsess over creating masterpieces, contemporary composers should “prepare the future for a new language in the world of music - not one but several languages - that are more closely connected to the needs of people.” [7]

In searching for compositional models that do integrate sacred character, authentic artistry, and noble accessibility, I have in fact found two wonderful sources of inspiration. The first is the harmonized liturgical chant of the Russian Orthodox Church, developed by composers such as Smolensky, Chesnokov, and Rachmaninoff. The second is the music of Jacques Berthier written for the ecumenical Taizé Community in France, which has brought an elegant simplicity and power to the singing of sacred texts by very large groups of people. In each of these cases, composers with highly sophisticated skills have deliberately set aside the kind of harmonic and rhythmic complexity appropriate to the concert hall, in order to bring intense depth and beauty to simpler forms that thus become nobly accessible to “common” people from a wide variety of backgrounds. Both of these sources have been my constant companions in the composition of this musical setting of the Mass.

St. Philip Neri

I have chosen to name this work in honor of Philip Neri, because his life and apostolate, which effected such a great spiritual and cultural renewal in 16th century Rome, have also been an ongoing inspiration to me and the choirs that I have had the privilege of directing. Through his Oratory movement, which combined prayer, study, works of mercy, joyful fellowship, and the cultivation of the arts, he became a patron to great composers such as Palestrina and Animuccia. Influenced by the contagious holiness and joy of St. Philip, they were able to create a magnificent new repertoire of sacred polyphony, rooted in the ancient tradition of Gregorian chant, but also responding to the new needs and inspirations of their day. My hope and prayer is that the Mass of St. Philip Neri might be one small flame in a similarly authentic renewal of sacred music, faith and culture that is so needed in the Catholic Church today!

Paul Jernberg Clinton, Massachusetts February 24, 2012

You shall sprinkle me, listen here

[1] Musicam Sacram, Art. 59; quote from Sacrosanctum Concilium, Art. 23

[2] Sacrosanctum Concilium, Art. 121

[3] Comments by Pope Benedict during a concert conducted by Dominico Bartolucci, June 24, 2006.

[4] The word ‘profane’ here is used in its first meaning, which is ‘outside the temple’ (Gr. pro - fanus).

[5] Sacrosanctum Concilium, Art. 14

[6] Riccardo Muti interview with ANSA.IT, May 27, 2011

[7] John von Rhein interview with Muti in the Chicago Tribune, January 29, 2012

The Thomas More College approach to Music in the Liturgy

The choir at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts is busy learning a repertoire for the Mass and the Liturgy. The aim is to have a repertoire that is small enough that each piece is heard often enough by those who are not in the choir that they can become familiar and sing along. At the same time it must be large enough that there is some variety in the music.

In regard to the choice of pieces, we have in mind also the principle of noble simplicity. Again this is to facilitate active participation of the laity in the liturgy. Accordingly we try to choose music that that is appropriate, simple and beautiful. We choose predominantly chant and traditional liturgical hymns and polyphony, with the idea in mind that it should be simple enough so that most people can quickly learn to sing it and it is beautiful enought so that they are motivated to do so.

The choir at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts is busy learning a repertoire for the Mass and the Liturgy. The aim is to have a repertoire that is small enough that each piece is heard often enough by those who are not in the choir that they can become familiar and sing along. At the same time it must be large enough that there is some variety in the music.

In regard to the choice of pieces, we have in mind also the principle of noble simplicity. Again this is to facilitate active participation of the laity in the liturgy. Accordingly we try to choose music that that is appropriate, simple and beautiful. We choose predominantly chant and traditional liturgical hymns and polyphony, with the idea in mind that it should be simple enough so that most people can quickly learn to sing it and it is beautiful enought so that they are motivated to do so.

For Latin we choose traditional chant aiming for familiarity with chant Masses for weekdays, Sundays, Marian Feasts and Feastdays and Sundays during Lent and Advent. These are introduced gradually, so that there is a slowly growing core repertoire. We are very lucky to have Dr Tom Larson of the Schuler Singers coming to the college to teach us. He posts audio files of those things that we need to learn so that we can download them. I am now the proud owner of an ipod! So I download these files and sing them as I drive into work every morning. We are a choir learning at the beginning so we are not capable yet of anything beyon simple polyphonic pieces (never mind the rest of the congregation). But for most part, the assumption will be the polyphonic pieces are an invitation to meditation on the part of the congregation. Accordingly the degree of polyphonic content would always be chosen so that the degree of active singing participation is balanced with listenting so as to encourage even on these occasions an engaged contemplation of the liturgy (which is another aspect of active participation in the liturgy of course).

When seeking to get the music in the liturgy going at the college, especially chant in the liturgy of the hours, I took advice on what might be the best way to do it. A useful piece of advice that was given to me by Fr Frank Philips of St John Cantius in Chicago. He suggested that we pitch the singing down so that it is always comfortable for men to sing. He said that the women will be more able (and more inclined!) to sing lower than the men will be able to sing higher. This was important to me, because I wanted the males students to develop the habit of singing their prayers without being self-conscious about it.

When seeking to get the music in the liturgy going at the college, especially chant in the liturgy of the hours, I took advice on what might be the best way to do it. A useful piece of advice that was given to me by Fr Frank Philips of St John Cantius in Chicago. He suggested that we pitch the singing down so that it is always comfortable for men to sing. He said that the women will be more able (and more inclined!) to sing lower than the men will be able to sing higher. This was important to me, because I wanted the males students to develop the habit of singing their prayers without being self-conscious about it.

The hope in engaging the men in the college is to re-establish the idea that prayer is a masculine thing and so promote the idea that fathers can lead the family in prayer; and perhaps also encourage vocations to the priesthood. The audio files that Tom posts for us are pitched lower than many other chant resources I have come across and so are comfortable for most amateur male voices. This has encouraged a more vigourous masculine sound to the chant. Wherever possible we sing antiphonally, separating men and women. This allows each voice to flourish separately in a complementary rather than a competitive way.

For variation we sing some of the Propers and Latin hymns with an 'organum' - a very simple but beautiful harmony. If you listen to this version of Stabat Mater, you hear occasionally a simple harmony behind the chant. It always strikes me that is mimicking the echo that is there if you sing in a church that is built acoustically for chant, such as a gothic abbey. I am an oblate of Pluscarden Abbey in Scotland, which is a medieval building. When I am there the harmonising echo that resonates, complements the singing and always suggests to me the voices of the angels and saints in the heavenly liturgy which we know, objectively, are singing with us.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=muJccdJJrwk

The occasional use of organum opens the imagination of the listeners to the implied harmonies that are present in the intervals of pure chant.

For the vernacular we look to the traditions of harmonised Anglican chant and also Eastern tones. Latin emphasises syllables in a very different way to English. Consequently, plainchant, which was developed over centuries to suit the rhythms and patterns of the Latin language is difficult to adapt to English. The Anglicans had a centuries old tradition of doing this and from it has developed a distinct tradition. I have interpreted Pope Benedict XVI's creation of the Anglican Ordinariate and his attendance at Choral Evensong when he visited last year as a sign that we have been encouraged to look at it as a resource for the vernacular. in the link below you can hear an Anglican adaptation of the Latin tonus peregrinus (which is itself an adaptation of a tone from the pre-Christian Jewish liturgy). While the harmonisation will require a choir, all the students are taught to sing the basic melody and they pick this up very quickly indeed.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9f4_IhaSnVw

Because the Greek and Slavic languages have a punchier rhythms and stresses on the consonants, the music of the Eastern liturgy has, it seems to me, been adapted to English much more successfully. We have been using some of the harmonised tones in our own liturgy too.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WkqZbFQb0O0&feature=related

We have found that when these are rooted in the rhythm of speech and musically are in modal form, it is possible, with careful choice, to have a unified feel to the music of the liturgy while relying on these different sources.

Much of what we do is adapted to make it simple for many to join in. I hope gradually (assuming I can cope with the technology) to start posting examples of our choir singing these adaptations.

Readers may also like to know that the Schuler Singers are singing at the installation of the new Bishop of New Hampshire, Most Reverend Peter A. Libasci on December 8th, 2pm at St Joseph's Cathedral in Manchester, New Hampshire.

Lotti's Crucifixion - Liturgical Music for Holy Week

As part of our build up to Easter during this Holy Week, here is a posting by professional chorister, Elizabeth Black, about a piece by the 17th century composer Antonio Lotti: his Crucifixion. Elizabeth sings in the choir of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington DC and this will be part of their Good Friday liturgy. Written especially for The Way of Beauty blog, she brings the special insight of the performer to the discussion. (I have embedded the music below, on some sites you will need the link that says 'Watch on You Tube'.)

As part of our build up to Easter during this Holy Week, here is a posting by professional chorister, Elizabeth Black, about a piece by the 17th century composer Antonio Lotti: his Crucifixion. Elizabeth sings in the choir of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington DC and this will be part of their Good Friday liturgy. Written especially for The Way of Beauty blog, she brings the special insight of the performer to the discussion. (I have embedded the music below, on some sites you will need the link that says 'Watch on You Tube'.)

"We are entering upon Holy Week and I am reminded, as I am every year, why I spend long hours singing. You see, it is during Holy Week that the full force of the beauty of the liturgy and its music springs upon us musicians; and it takes me by surprise every time. This Lenten music is haunting and expresses the full and intense love of the Church for her Sacrificial Groom. This year, we will be singing Lotti’s (1667-1740) Crucifixus during the Good Friday service. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=khJtf8WMMeY&feature=player_detailpage

The first thing that jumps out is the dramatic shift from transparency to density in the first few measures of the piece. Beginning with a simple 3 notes quietly sung by the bass, the music swells quickly into the 8 different musical lines (called voices), each voice entering with the similar motif. These varying 3 notes sung by each line bump up against each other in buzzing collisions of notes, usually when an individual line is singing “fi” of “crucifixus”. It is a kind of delicious pain. This sets up the mood of tension and anguish which the faithful feel upon gazing at the death of the Lord.

Immediately after this dramatic first section, the simple word “crucifixus” repeats in a new musical phrase (0:50), but this time with the pulsating repeated notes “crucifixus etiam pro nobis” (he was crucified for our sins). The music ebbs and flows here like water, overlapping itself in waves of sound. The image which comes to mind when I sing this piece is the blood and water flowing from Our Lord’s side.

But out of this lull (1:15-1:40), rises the soprano voice announcing “passus et sepultus est” (having suffered and was buried) at 1:47 and 1:54. The effect of this lull and sudden rise of intensity imitates the natural waves of emotion. Think of some violent fit of weeping: the intense sobs are interspersed with quieter sobs. With this “passus”, the sobs come on again, and the violent weeping only subsides with the end of the piece.

The last few measures are full of lusciously intense chords (2:13) while the piece rallies itself one last time to declare that Christ suffered and died. The emotional punch of 2:13 is due to the fact that each voice has been singing the same text up to this point, but at different times. This is called polyphony-from the Greek for “many voices”. However, at 2:13, the entire choir sings “passus” simultaneously (this is called homophony) before moving back into polyphony. The chords seem to be searching for resolution, as the sopranos wait on top, patiently holding their note while the other voices progress from dissonant chord to dissonant chord. The effect is expectant suspense which is only heightened by the lengthening of the unresolved penultimate chord. And finally, after expecting it for measures, resolution and soothing of the emotions comes in the final chord.

-792835.jpg) Lotti’s “Crucifixus” is three minutes of emotional distress and anguish as the music takes the listener through a meditation on the pain and trauma of the crucifixion. This piece expresses through sound the emotion that the Church and her members undergo (passus!) during Holy Week as we relive the death of our Lord. However, this piece is not a journey in painful emotion merely for its own sake. For after journeying though emotional anguish, Lotti gives his listeners the resolution of the final chord. Just as after the pain and sadness of Good Friday, when Our Lord has died and been buried, Christians find hope that Easter Sunday will come."

Lotti’s “Crucifixus” is three minutes of emotional distress and anguish as the music takes the listener through a meditation on the pain and trauma of the crucifixion. This piece expresses through sound the emotion that the Church and her members undergo (passus!) during Holy Week as we relive the death of our Lord. However, this piece is not a journey in painful emotion merely for its own sake. For after journeying though emotional anguish, Lotti gives his listeners the resolution of the final chord. Just as after the pain and sadness of Good Friday, when Our Lord has died and been buried, Christians find hope that Easter Sunday will come."

Elizabeth Black will teach the two-week workshop on Gregorian chant at Thomas More College's Way of Beauty Atelier this summer. The course teaches the student how to sing Gregorian chant through training in sight-singing and the study of chant theory. To this end, the students will chant the Divine Office and the Mass daily. The class day is centered on and receives its fruition in the liturgy, with classes culminating in a fully sung final Mass in the Thomas More Chapel. Studies will also include a survey of chant history, a discussion of the principles of Sacred Music and their implementation in parish life. Students will leave with a deeper understanding and appreciation of Sacred Music and with the tools necessary to continue chanting on their own.

It will take place while the art classes of the atelier are being held. Each evening there will be lectures that will appeal to attendees at all three Way of Beauty Atelier classes that place art, architecture and music in the broader context of Catholic and Western culture. This promises to create a unique and stimulating dynamic.

The images are of Pilate washing his hands by Duccio; and the Resurrection by Fra Angleco.

-792835.jpg)

Concert of Music from the Sarum Rite

This is sacred music from pre-Reformation England. Sarum is old name for the town of Salisbury and it disappeared as a form of the Church's liturgy after the Council of Trent. However, it was retained in some form as it became the basis of Anglican church music and for the Book of Common Prayer. The concert takes place in a New York Episcopalian church - Trinity Church. I heard about it because it was posted onto my Facebook page by a TMC student who is currently out in Rome - thanks Taylor! Access the video through the image of Salisbury Cathedral below.

An Englishman Meditates on Thanksgiving and Psalm 114

We had a banquet at Thomas More College in New Hampshire before people dispersed for Thanksgiving. Before the dinner we chose to chant the first 8 verses of Psalm 114 - 'When Isreal came out of Egypt' in order to help us meditate on the meaning of this very American holiday.

When the people of Israel, the subject of the psalm, left Egypt they had two goals. The first was to worship and serve God; and the second was to occupy the Promised Land. On their journey they stopped at Sinai. Here they received their instructions for worship and for a rule of life, before moving on to their final destination. That pause in their journey is significant.

We had a banquet at Thomas More College in New Hampshire before people dispersed for Thanksgiving. Before the dinner we chose to chant the first 8 verses of Psalm 114 - 'When Isreal came out of Egypt' in order to help us meditate on the meaning of this very American holiday.

When the people of Israel, the subject of the psalm, left Egypt they had two goals. The first was to worship and serve God; and the second was to occupy the Promised Land. On their journey they stopped at Sinai. Here they received their instructions for worship and for a rule of life, before moving on to their final destination. That pause in their journey is significant.

‘Sinai, in the period of rest after wandering through the wilderness, is what gives meaning to the taking of the land. Sinai is not a halfway house, a kind of refreshment on the road to what really matters. No, Sinai gives Israel, so to speak, its interior land without which the exterior one would be a cheerless prospect. Israel is constituted as a people through the covenant and the divine law it contains.’(Pope Benedict XVI, The Spirit of the Liturgy, p19)

There are obvious parallels between this and the popular story of Pilgrim Fathers for which Thanksgiving has become a focus. They, like the Isrealites, had worship in mind. They were seeking to institute a sort of religiously based community; and the land they settled in is the land of plenty we now live in. But we would do well to remember also, that it is always a ‘cheerless prospect’ without its Sinai – the interior life that is available to us in its fullest expression through the Church.

There are obvious parallels between this and the popular story of Pilgrim Fathers for which Thanksgiving has become a focus. They, like the Isrealites, had worship in mind. They were seeking to institute a sort of religiously based community; and the land they settled in is the land of plenty we now live in. But we would do well to remember also, that it is always a ‘cheerless prospect’ without its Sinai – the interior life that is available to us in its fullest expression through the Church.

But there is something greater that both point to. All of us in this life are constant pilgrims on that journey in its highest form, the pilgrimage to heaven – that quotation was taken from Pope Benedict XVI’s book on the liturgy. He describes the pilgrimage not seen as as a straight path. Rather, he talks of a constant liturgical dynamic of exitus and reditus – leaving to return home, but each time it is a fresh new home, when we step into the supernatural made present by the Eucharist at the centre of the liturgy. Rather than an enclosed circular motion of repeated worship, it is a helix, in which each cycle takes us further upward. (I explore this idea further in another article, The Path to Heaven is a triple Helix.) Quoting Pope Benedict again, ‘in the Christian view of the world, the many small circles of the lives of individuals are inscribed within one great circle of history as it moves from exitus to reditus’. This is why the liturgy, the formal worship of the Church is described as both ‘source and summit’ of human existence. It is both our supernatural launch pad, a source of grace, and landing field, the heavenly activity is liturgical – the perfect, joyful exchange of love in perpetuity .

It is interesting that the Pilgrim Fathers’ journey began in Plymouth and ended in a new Plymouth – Plymouth Rock; and similarly ironic that the one thing that would truly have grounded it in an unmoveable rock was supernatural. The Catholic Church that they did not accept. We, because we are aware of this, are in that privileged position of being pilgrims who have that sure and certain guide to our final destination, one that has its foundations in rock, not Plymouth Rock, but the rock of Peter. Then our home, wherever it may be, can be (referring to the psalm) both Judah and Israel, sanctuary and dominion.

It is interesting that the Pilgrim Fathers’ journey began in Plymouth and ended in a new Plymouth – Plymouth Rock; and similarly ironic that the one thing that would truly have grounded it in an unmoveable rock was supernatural. The Catholic Church that they did not accept. We, because we are aware of this, are in that privileged position of being pilgrims who have that sure and certain guide to our final destination, one that has its foundations in rock, not Plymouth Rock, but the rock of Peter. Then our home, wherever it may be, can be (referring to the psalm) both Judah and Israel, sanctuary and dominion.

That is true cause for gratitude on Thanksgiving day.

(As an interesting side note: even the psalm tone that we use to sing Psalm 113 is appropriate to the theme. The ancient tonus peregrinus is always used for this psalm. This translates as 'pilgrim tone' and which was adapted from the pre-Christian Jewish liturgy. We sang it as Anglican chant which adapts the tone to English, and uses four-part harmony.)

Paintings: top, Poussin: Moses String the rock to give water in the wilderness; and above, also Poussin, the Iraelites gathering manna in the wilderness.

Listen to Music by Frederick Stocken

Frederick Stocken is a Catholic composer who composes genuinely high quality classical music that actually sounds good. There is no hint of either dissonance or minimalism in his work (which seem to be the two streams that most modern composers occupy). I was lucky enough to hear his First Symphony performed at the Albert Hall in London under the direction of Vernon Hanley several years ago (I was reviewing it for the Catholic Herald). This was my introduction to his music and I have been following his work, which has steadily grown and developed, ever since.

I was pleased to hear recently that Frederick Stocken's premiere of his organ work, St Michael the Archangel was well recieved and he has been asked to perform it again when the Archbishop of Westminster visits Poplar in December. Frederick seems to be working hard at the moment and there is another premiere, this time a piece for organ and choir, commissioned by the Worshipful Company of Musicians for their carol service at St Michael's in Cornhill, London in December.

Unfortunately, there is very little of his work available on CD. There are clips of some of his work at www.frederickstocken.com . If you want to hear a complete piece his charming Bagatelle for piano is played in full.

His early work, Lament for Bosnia, which made the classical charts some years ago now is out of print but still seems to be available on Amazon. I look forward to the day when more of his work is available.

The Music of George Sarah

Drum, bass 'n violins I would like to bring to your attention the music of composer George Sarah. George is a Catholic who lives in Los Angeles and since 1985 has regularly been commissioned by film and TV companies to compose scores for their programming. I won’t go through the names, but his portfolio is impressive. He works for household name shows, as his MySpace page reveals. I came across him when I first visited Los Angeles about 4 years ago. A Catholic friend had organized for me to teach an icon painting class at St Monica’s Church in West Hollywood. George just happened to hear about this and keen to help, arranged promotional interviews for community radio and TV. You can see the TV show through the panel, right.

Drum, bass 'n violins I would like to bring to your attention the music of composer George Sarah. George is a Catholic who lives in Los Angeles and since 1985 has regularly been commissioned by film and TV companies to compose scores for their programming. I won’t go through the names, but his portfolio is impressive. He works for household name shows, as his MySpace page reveals. I came across him when I first visited Los Angeles about 4 years ago. A Catholic friend had organized for me to teach an icon painting class at St Monica’s Church in West Hollywood. George just happened to hear about this and keen to help, arranged promotional interviews for community radio and TV. You can see the TV show through the panel, right. The music for the opening sequence is one of George’s pieces. This was filmed before I was recruited by Thomas More College and moved to New Hampshire. He writes music for his separately released CDs (or whatever the latest mode of recording via computer is!) and performs his work in concert.

His style has been described as electronic chamber music. He performs with a traditional string trio, but accompanies them on electronic keyboards and drum machines. It has a haunting quality and a modern feel but, and I think it is more than simply the choice of instruments, it has a sense of traditional form about it as well.

The music for the opening sequence is one of George’s pieces. This was filmed before I was recruited by Thomas More College and moved to New Hampshire. He writes music for his separately released CDs (or whatever the latest mode of recording via computer is!) and performs his work in concert.

His style has been described as electronic chamber music. He performs with a traditional string trio, but accompanies them on electronic keyboards and drum machines. It has a haunting quality and a modern feel but, and I think it is more than simply the choice of instruments, it has a sense of traditional form about it as well.

If we are to evangelise the culture, then it must be rooted in the Mass. For the Mass, it is important that we employ traditional forms that are united to the liturgy. However, once we go out of the church building it is legitimate, I think to develop them into other profane (ie non-sacred) forms that grab people and then direct them towards the Mass. We are required to develop a culture of beauty that both speaks to modern man and opens up the hearts of men to God’s grace. George is consciously seeking to do this by working within the world of popular music.

If asked he will talk freely and enthusiastically about his conversion, which he attributes to Mary; and his desire to draw people into the Church. However, within the context of his music it is through form rather than words that he seeks to do it. He aims for beauty that elevates the souls of men to God. He is self taught and composes by developing melodies on the keyboard and then building the harmony and counterpoint around it instinctively. To my mind George is doing something very important here. While I firmly believe that the most beautiful music is that which is united to the Mass, plainchant and polyphony, not all are attracted to it immediately. It is an adage in all evangelization that you have to meet people where they are and take them to somewhere better. George’s music heard by many who would never hear Palestrina and is quite different structurally, but I do feel that it is nudging their souls in the Palestrina’s direction.

Some argue that pop and good music are a contradiction in terms. Certainly, I would say, much pop music is detrimental to the soul (and intentionally so). But it is not true of all it. What opened me up to classical music (and who knows, the beauty of God and my eventual conversion some years later) was the music of a band in the 1970s who were writing rock music but consciously employing classical, rather than blues based forms. The early music of Genesis (we are talking pre1976 here, for example the track, The Firth of Fifth) was cutting edge and trendy at the time so as a teenage schoolboy I could contemplate listening to it. I would never, ever, have chosen to listen to ‘Christian rock’, which just made me cringe with embarrassment…and it still does. Genesis did not write their music as an evangelical tool at all (none are Christians to my knowledge) but its use of traditional form, with intelligently applied rhythms pulled me in and sent me off in the right direction. I have spoken to a number of people since who have said the same. I doubt that 1970s rock will pull in many today, but the idea is still good, and this is what George is doing in a current idiom. It is interesting that he does not see his music as something that is used the context of the Mass. Firmly orthodox, he loves the Latin Mass and would always want to see the traditional forms of plainchant and polyphony.