Do you want to study choral singing with Gabriel Crouch, Sir James MacMillan and Paul Jernberg? Go to sacredmusicproject.org and sign up. Catholic Sacred Music Project Choral Institute, June 9-15, Princeton, NJ

Catholic Sacred Music as a Radiant Witness: A Workshop led by Paul Jernberg in Kansas, May 31st - June 3rd

Summer 2022 Sacred Music Classes St. Joseph’s Seminary Yonkers, New York, online or in-person

New Online Classes in Gregorian Chant and Sacred Music from Jenny Donelson

Sacred Music Symposium in British Columbia, July 2020

Biblical Typology for Christmas in a Liturgical Hymn: Words, Music and Art

EnglishMotets.com: Traditional Latin Polyphony in English Translation

Why Do So Many Choir Directors Have “Van Gogh’s Ear for Music”?

The choice of music at Mass matters to me. It was hearing polyphony and chant done well that contributed to my conversion. It was hearing practically every other style of music in church that contributed to my not becoming a Christian until I did.

The choice of music at Mass matters to me. It was hearing polyphony and chant done well that contributed to my conversion. It was hearing practically every other style of music in church that contributed to my not becoming a Christian until I did.

I grew up hearing Methodist hymns in church, and today I can’t bear to sing them or any other “traditional” 19th century-style hymn, even if the words are written by Fr Faber. I hate Christmas carols and find them sentimental. I had grown tired of Silent Night and Ding Dong Merrily on High before I was 10 years old, and today always refuse to go caroling in the neighborhood on the grounds that I don’t want to chase any more people away from the Church.

I find the attempts to be musically current in church even more repellent. Whether it’s the Woodstock-throwback-with-added-sugar of the standard pew missalet, candied Cat Stevens presented by a cantor in a faux operatic or broadway-musical style, or the more recent equivalents, imitations of the pop music of the moment to “get the young people in,” it’s all the same to me. If ever there was an award that labels a musical artist as a legend in his own lunchtime, it’s “Christian album of the year.” Attempts at being Christian and cutting edge always seem outdated five minutes after they were composed, and most weren’t that great for the four minutes they were relevant.

Whenever I am in church and expected to sing along to such inventions, I shift uneasily and look down at the ground, hoping nobody notices I’m not joining in. (That’s assuming I can hit the pitch, which is usually too high for most men anyway.) It is an attempt to appeal to young people that feels to me like an imitation of the foolish parent who tries to hard to be liked by his adolescent children by adopting inappropriate teenage fashions; he inevitably misses the mark, and loses self respect and the respect of the younger generation in the process. To my mind, there’s nothing more embarrassing than a grown-up trying to be hip and groovy when the words “hip” and “groovy” haven’t been hip and groovy for a long, long time. I thought that when I was 13-year-old atheist and I still think it today.

And I’m not just talking about the music for the Novus Ordo or the Masses in the vernacular. I am amazed at how often I struggle at the choice of hymns and the sentimental Masses from the 19th or early 20th century that some choir masters seem manage to dig up when given the freedom to choose music for the Extraordinary Form. Where do they get them from?

All of this music drives me to distraction; and before I heard chant and polyphony and found out there was something different, it drove me to atheism too.

Am I am unusually narrow minded and intolerant in regard to music? Well, in the context of the liturgy. I am very likely spoiled by having had the benefits of the choirs of the London Oratory and Westminster Cathedral, or occasionally Anglican chant at Choral Evensong at one of the great Anglican cathedrals in England.

But I should point out that as long as I can remember, and long before I converted, my gut reaction told me that contemporary styles of Christian music were just the epitomy of “naffness,” to use the English colloquialism. Even when I was a schoolboy in Birkenhead, the bad musical taste of Christians gave me plenty of ammunition for deriding them for trying to be trendy when they “didn’t have a clue.”

Furthermore, I don’t think I am overly traditional or reactionary about music in other contexts. I don’t believe that it all went downhill after Bach, for example, or with Wagner (the Siegfried Idyll is one of my favourite pieces). I enjoy operas, swing, jazz, and pop music. I play Appalachian Old Time on my banjo (very badly, and if you’re interested, my favorite Old Time tune is called Waiting for Nancy.) I sing the pop songs from my past when I’m driving and think nobody is listening - Stephen Bishop’s sentimental love songs, Rory Gallagher’s Wayward Child, Betty Boo’s Where Are You Baby or Stereo MCs’ Connected. (I lost touch with the pop world after 1992).

But I have never thought that any of this was music for the liturgy.

For a long time after my conversion, if I couldn’t get to the Oratory, I would seek out a spoken, low Mass. If I visited a church for the first time, I picked an early morning Mass in the hope that the parish didn’t have the resources to put on any music that early. But even then I found that it’s not unusual for the 7:30 am to have a troop of local schoolchildren doing a hand-bell version of Immaculate Mary for the Offertory. I don’t think I am alone in this.

Although the others in attendance will probably not have exactly my taste in music, there will be many who are as strong in their likes and dislikes as I am, and will most probably dislike the music at Mass as much as me.

I would maintain that it is the music at Masses that has contributed as much to the the drop off in the numbers attending as any other factor. Putting aside those who attend the rare parishes that offer predominantly chant and classic polyphony, for the most part the only people left in the pews of most churches are the tone deaf, those who have sufficient faith to offer up the pain of listening to music they hate, or the very small number of people who actually like what they hear.

Whenever I bring this up with priests, their concern is for those who currently go to Mass. The priest will tell me that for “pastoral” reasons, he has to be careful about changing things, as he doesn’t want to offend people and drive them away. This is an understandable reaction, but my thought when I hear this is that for every person who is enjoying the music in Mass, there are a ninety-nine more who don’t like it, and most of these 99 people don’t come to church at all, and won’t as long as the music stays as it is. I always want to ask the question: when are we going to start being pastoral to the 99% outside the church and stop pandering to the 1% (if I can borrow a slogan from elsewhere!)

But even if there is a desire to create attractive music? What music should we choose?

Perhaps we could just cut out all modern forms and stick exclusively to chant and polyphony? Unlike all the other styles mentioned above, we can say objectively, regardless of personal taste, that according to the tradition of the Church these styles are appropriate for the liturgy.

I think therefore a switch to chant and polyphony across parishes would help and attendance at Mass would increase a little bit, after an initial drop. Some people will respond to it immediately, and others will grow to like it. But I don’t think this measure alone would be enough. Not everyone will persist in developing that taste unless there is other music that can be accessible to them, and lead them into an appreciation of the canon of great works.

This has been pointed out by popes in the past. While asserting the centrality of chant and polyphony, Popes such as Pius X and Pius XII have also acknowledged the need for new compositions in the liturgy. For example in Mediator Dei, Pius XII wrote:

'It cannot be said that modem music and singing should be entirely excluded from Catholic worship. For, if they are not profane nor unbecoming to the sacredness of the place and function, and do not spring from a desire of achieving extraordinary and unusual effects, then our churches must admit them since they can contribute in no small way to the splendor of the sacred ceremonies, can lift the mind to higher things and foster true devotion of soul.'

The necessity of accessible contemporary forms as well as the canon of traditional works is the message of Benedict XVI’s book, A New Song for the Lord; Faith and Christ and Liturgy Today. And he places the responsibility for making it happen on the artist or composer, telling us that it is the mark of true creativity that an artist or composer can “break out of the esoteric circle” – i.e., the circle of their friends at dinner parties – and connect with “the many.”

This grave responsibility is one that thus far, it seems to me, the vast majority of Christian artists in almost every creative discipline have not been able to take on. That is not to say, however, that the task facing creative artists today is easy. Indeed, it may be so hard than it needs an inspired genius in any particular field to show us the way before it can happen.

One thing is clear to me: we need a fresh approach. And contrary to what many seem to think, most music in churches today is not broadly popular. It is strongly disliked.

Dr Peter Kwasniewski recently wrote a very good piece for the blog OnePeterFive, highlighting the difficulties in adapting modern forms of Western music to music appropriate to the liturgy. He and I both think that what has been done in the last 50 years particularly has been largely disastrous. He doubted that it could ever be done because of the special nature of modern culture. I agree that it is difficult, but for all that the style of modern music speaks of the secular world, I am a little more optimistic than him. The task is difficult certainly, but I hold out hope and argue that just because it has been done badly up until now, it doesn’t mean that it can’t be done well in the future.

Here is one particular difficulty that composers are going to have to overcome if they are to engage with modern culture successfully (and prove me right!). This arises from the fragmented nature of modern culture.

Contrary to what I have heard many say, I don’t believe the general population today is musically ignorant and uncultured. Modern society is highly musical and has sophisticated taste. More people enjoy music and have access to a greater range of styles from all periods than ever before, and they are choosing what appeals most. Most people are not ignorant, for example, of what classical music is, even if they have only heard it in a film score. The problem is that this sophistication is one that fragments rather than unifies. People today know what they like and dislike, and they are sensitive to even subtle changes in style, and will react strongly to them. Within any genre, there are myriad sub-genres that are discernible to devotees and who discriminate between them. And even within the same sub-genre, people will strongly favor one artist, but react strongly against another; hence the cliché that those who like the Beatles hate the Stones. (I am a Beatles person, by the way). This sophisticated level of discrimination exists in every genre of popular music up to the present day. Furthermore, the scene changes rapidly. What was popular with teenagers a few months ago is now forgotten. And at any moment, what is popular with teenagers is not liked generally by the rest of the population.

As a result, there is no form of secular music that I know of, classical or contemporary, that currently exists and will appeal to all people. This is why choir directors should not blamed so much for introducing music that is so disliked. Given the compositions available to them, it is almost inevitable that their choices will be disliked by most people. (Where criticism is fair, I think, is where the choice of these modern forms supplants, rather sits alongside, traditional chant and polyphony.)

So, although virtually nobody will share my tastes in music, there will be very many people, I suggest, who are like me in having a strong sense of what they like and dislike, and because they are used to being able to choose the music they listen to, very little tolerance for what they don’t like, however unrefined that taste may seem to others. This is why, as one newly appointed choir director described to me, a parishioner approached him and told him that he was worried that the music at the church would change because he was “very traditional.” “Oh, that’s good,” said the choir director, “I’m pretty traditional too.” “I’m so glad,” said the parishioner, with obvious relief, “so we’ll still have the music we’ve always had, especially my favorite traditional tune, On Eagles Wings.”

So we can see why, in my opinion, any musical form composed for the liturgy that is obviously derived from any contemporary music style or past style that has not transcended its own time (and I would put all the commonly sung hymns into this category) will almost certainly be disliked by the majority.

Therefore, we need a fresh approach. This, I suggest, will be radically different from the superficial analysis that has produced “contemporary” Christian music. Musicologists will have to get deeper into the embedded code that unites the forms of modern music together, build on what is good, reject what is bad, and incorporate these into the essential patterns of interrelated harmonies and intervals in a form that also satisfies the essential and universal criteria of liturgical music. If these are played in church alongside chant and polyphony, the appropriateness of such music will become apparent even to many who do not consider themselves music experts. To the degree that a composer is successful, the new compositions will not only connect with people today, but will transcend their own time, with the best examples being added to cannon of great works.

If I am wrong, and however penetratingly we search for it, this common code of modernity that is essentially good does not exist, then Peter is right! There is a reason for my optimism, however, for I do see some modern compositions that do seem to me to be accessible to more people, and which are appropriate for the liturgy.

Some of the very best of these examples (although not all by all means) seem to occur in works composed for the vernacular. It seems that seeking the principles that connect music to language at the most basic level, forces composers into that territory where they are beginning, at least, to access a common code for the culture, which today springs from the vernacular. Those that do so in such a way that they respect also what is essential to chant and polyphony, create the beginnings of this crossover music. I have noticed also that modern composers look with some success to Anglican and Eastern forms of chant for inspiration. The result is successful when it seems both of our time, and of all time. Some of the people who come to mind immediately who are doing this are Adam Bartlett, with his material available through Illuminare Publications, Fr Dawid Kusz OP at the Dominican Liturgical Center in Krakow (who composes for the Polish language), Paul Jernberg, Roman Hurko, Adam Wood, Frank LaRocca and our own Peter K. There are more I am sure. What is interesting to me is that the successes in the vernacular can then feed back into composition for Latin. Paul Jernberg composed his Mass of St Philip Neri for the English Novus Ordo. It was so admired by one patron that he commissioned Paul to write a setting for Ecce Panis Angelorum and he has also composed for the Latin Ordinary - appropriate of course for both OF and EF.

I do not know for certain if all, or indeed any of these composers are the trailblazers to whom the future will look back, as we today look back to Palestrina. Only time will tell. But I do feel sure that theirs is the type of approach that we should be aiming for, and is the one that will succeed in the end.

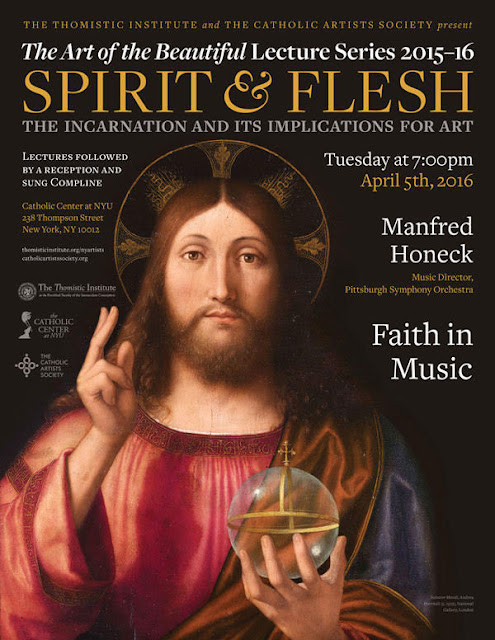

International Conductor to Address Catholic Artists' Society in NYC

Born in Austria, Honeck has worked to great acclaim with the world’s leading orchestras including the Berlin Philharmonic, Vienna Philharmonic and the London Symphony Orchestra, . In the United States, Honeck has conducted the New York Philharmonic (with whom he is appearing next week), The Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra and Boston Symphony Orchestra.

His talk is entitled "Faith in Music." A reception and sung Compline will follow.

Listen to this Chant in English

Chant that Competes With Praise and Worship Music! I have been contacted by a seminarian based in Boston called Pat Fiorillo who directs the choir of a young adults group in Boston.

He told me that through his influence of introducing this sort of music at groups he has worked with, he has seen a young people's group chant for the first time ever rather than singing only praise and worship music with the usual guitars and drums.

He sent me this recording of his group of singing the Magnificat to the Way of Beauty psalm tones composed by myself and with the harmonization by Paul Jernberg. They are singing it as a communion meditation for Mass on the Feast of the Assumption recently. The antiphon is composed by Paul Ford (whose work I otherwise know nothing of), but I must say that it sounds good. Pat is clearly working well with them, and I find their chant of the antiphon beautiful. They actually did all of the propers - introit and offertory also from Ford's collection - as well as Kyrie VIII, and Proulx's Missa Simplex.

From what he describes everyone is enthusiastic about singing sacred music and he is pleased to have something that works in English which opens the way for congregations who might be resistant if he insisted on Latin. What is particularly encouraging is that this is a seminarian doing this! I hope this gives us an indication of what are priests will be doing in the future.

[audio mp3="http://wayofbeauty.thomasmorecollege.edu/files/2014/08/Communion-Magnificat.mp3"][/audio]

New Setting for the Creed from Corpus Christi Watershed

Here is a new chant setting for the Creed composed by Jeff Ostrowski, who happens to be president of Corpus Christi Watershed. He has published a recording and scores, all available for download free on their website, here. He has also written a brief account of his approach to composition. My belief is that we will not see chant coming to the fore again until we see more composition of new material, for English and Latin, OF and EF. This is what will connect with the uninitiated and open the way to the full tradition. Also, it is important that as much as possible is freely available, because it creates a dynamic environment where people hear things and have a go themselves, both performing and composing. From this we will start to see something powerful emerging. I have just forwarded it to our choir director to see if he wants to make use of it. The proof of its value will be in the singing - do we find that the congregations respond?

There is one other point. When sung in a church with a good acoustic, part of the beauty of chant, I feel, is the combination of the melody with the harmonics produced by the resonance in the building. It accentuates the implied harmonies of the intervals in a beautiful way. It is so subtle that I always think of it as gently leading my imagination to harmonies in heaven and I think of the angel hosts singing the heavenly liturgy with us.

So many churches today do not have a good acoustic and so the chant will sound flat in comparison. In order to support the singers, sometimes the organ is played with chant. I understand from organists that this is a real skill in itself, but even when done well, the harmonies never match those that I sense from natural resonance. It always seems a little disappointing. However, my experience is that for some reason, a drone underneath - a very simple organum, not parallel fifths or fourths - seems to add to the beauty of chant much more powerfully than an organ accompaniment and lead the imagination in the same way, even when the acoustic is not good. It seems to bring it to life. Furthermore, my experience is that congregations always enjoy it and remark on it afterwards.

So, Jeff, please give us a drone to sing underneath! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4gCJiK8MoYg

How to Compose Psalm Tones for the Vernacular - Have a Go Yourself

Here's an article that I wrote and was first posted on the traditional music website, Corpus Christi Watershed. It is about the principles used when creating psalm tones for the vernacular. It explains the method by which the tones that are given on this site were developed at Thomas More College and how we tried to incorporate the principles of tradition when adapting tones from the old English Sarum Rite written originally for the Latin to the English. Read the full article here.

I always maintain that to be vital, every tradition must always have new forms that encapsulate its essential elements, but speak anew to each successive generation. This means that we cannot simply look at the past in regard to sacred music. We must also compose. If we don't the tradition will die again. So, in accord with that I say if you don't like what I have done then please think about creating something that you do like!

Here's an article that I wrote and was first posted on the traditional music website, Corpus Christi Watershed. It is about the principles used when creating psalm tones for the vernacular. It explains the method by which the tones that are given on this site were developed at Thomas More College and how we tried to incorporate the principles of tradition when adapting tones from the old English Sarum Rite written originally for the Latin to the English. Read the full article here.

I always maintain that to be vital, every tradition must always have new forms that encapsulate its essential elements, but speak anew to each successive generation. This means that we cannot simply look at the past in regard to sacred music. We must also compose. If we don't the tradition will die again. So, in accord with that I say if you don't like what I have done then please think about creating something that you do like!

The painting, by the way, is from 1808 by the French artist Granet of the choir singing in the Capuchin church in Rome.

The Music of Roman Hurko and the Principle of Noble Accessibility

• The noble accessibilty that needs to characterize all Catholic sacred music, is important both in congregational and choral music, each of which has an important place in the Liturgy.

• Whereas music composed for the congregation needs to be “singable”, music composed for choirs needs to be accessible to the minds and hearts of the congregation as they hear it! It needs to communicate in a musical language that the faithful can readily receive, and which through its beauty and sacred character lifts hearts to the transcendent.

• Yes, there might be some formation needed here, as those unaccustomed to the tradition of Sacred Music adjust to its contemplative nature. However, one should not be required to undergo extensive musical training in order to appreciate music in the Liturgy! The formation required will be more theological and spiritual, rather than musical.

• The choral music of Roman Hurko, composed for choirs singing the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom (Eastern Catholic Rite), is an eminent example of this noble accessibility in choral music. His melodies, harmonies and rhythms are composed in such a way as to communicate to the common man, a profound beauty that lifts the heart and mind to prayer.

• This aspect of listening as well as singing is important in the liturgy. Some settings or parts emphasize the vocal participation of the congregation; others, such as polyphonic settings in the Western tradition, call forth the more meditative participation of the congregation. Antiphonal singing, an important aspect of both Eastern and Western liturgical traditions, engages us in both ways. Sometimes this involves having the congregation divided into two groups, while at other times the antiphonal principle is manifested through the choir alternating with congregation. In the latter case, it is appropriate for the choir to sing more ornately beautiful and challenging settings, corresponding to their musical abilities, while the congregation sings simpler arrangements.'

As an artist I am always thinking about the parallels between sacred art and music. In the case of art participation is not a requirement - we don't expect everybody to be painting in church, that would be art therapy! But the other aspect of accessibility does apply. It is down to artists to work within the traditional forms in such a way that ordinary church goers will respond easily and willingly so that it raises their hearts and minds to God.

Roman Hurko's website is www.romanhurko.com; and a link through to his iTunes page, for anyone who would like to download his music, is here.

Paul Jernberg is Composer-in-Residence at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts, Merrimack, NH.

http://youtu.be/qdyGJUinKGE

The Logos of Sacred Music, by Paul Jernberg

A composer tells us his approach in composing works that are fresh and new, while reflecting the timeless principles that constitute sacred music. Listen also to his beautiful newly composed Mass.

The following is an essay written by the composer Paul Jernberg. Paul has composed his Mass of St Philip Neri for the new translation of the Mass. In the essay below he discusses the principles that guide him in composition and which enable him to compose new music in accordance with timeless principles. We have been singing his compositions at Thomas More College - I have been working with him in creating psalm tones for the vernacular that are modal and so sit within the tradition.This has enabled us to chant, for example, the traditional Latin proper for communion and then a communion meditation in English without any sense of disunity.

A composer tells us his approach in composing works that are fresh and new, while reflecting the timeless principles that constitute sacred music. Listen also to his beautiful newly composed Mass.

The following is an essay written by the composer Paul Jernberg. Paul has composed his Mass of St Philip Neri for the new translation of the Mass. In the essay below he discusses the principles that guide him in composition and which enable him to compose new music in accordance with timeless principles. We have been singing his compositions at Thomas More College - I have been working with him in creating psalm tones for the vernacular that are modal and so sit within the tradition.This has enabled us to chant, for example, the traditional Latin proper for communion and then a communion meditation in English without any sense of disunity.

What characterises both the compositions you can hear here and the music he has composed for us at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts is how simple it is to perform, yet how good it sounds. He really has hit that standard of noble simplicity - music that is so beautiful that you want to sing it, and so simple that you can. Furthermore, there is not even a hint of sentimentality in his music.

I have punctuated the text of his essay with links through to audio of the St Philip Neri Mass so that you can pause and listen as you read along. The attached audio files have been recorded by members of the Parish Choir of St. John's in Clinton, MA and of the Chorus of Trivium School, a Catholic high-school in Lancaster, MA (plus myself and Dr Tom Larson from Thomas More College of Liberal Arts and an additional member of Tom's amateur chant and polyphony choir, the Schuler Singers). Please bear in mind as you listen to them that they are not professional recordings and precisely because it is amateur singers that you are listening to it represents an endeavor to incarnate the ideal articulated in the essay on the Parish level:

The Logos of Sacred Music

An introduction to the Mass of Saint Philip Neri

The composition of this work has been my response to the need for a fitting musical setting of the Ordinary from the new English translation of the Roman Missal. In the creation of this music it has been my goal to fulfill three essential criteria, namely, that it have a true sacred character, that it be imbued with the qualities of authentic artistry, and that it possess a noble accessibility will allow it to be received into the hearts of ordinary people of good will throughout the English-speaking world.

Sacred Character

Music in the Liturgy of the Catholic Church should by its nature have a distinct identity that is contemplative, vibrant, and rooted in ancient tradition. In the perennial Catholic vision of the Liturgy, all of its sensible elements are intended to provide a sacred space that is worthy to welcome the sacramental Divine Presence. This intention would seem to surpass the reasonable scope of ordinary human creativity, as the finite aspires to welcome the infinite, the creature to create a worthy space for the Creator. And yet, both faith and aesthetic sensitivity perceive that an inspired tradition has indeed developed over the course of the centuries – including aspects such as architecture, visual arts, and music - which has fulfilled this task in a marvelous way.

In the West, this inspired musical tradition has as its foundation a vast repertoire commonly known as Gregorian Chant. Any composer who wishes to approach the task of composing music for the Roman Catholic Liturgy in a serious way, should thus be thoroughly versed in the study and performance of this repertoire, realizing the littleness of his own efforts in relation to the greatness of the tradition. The composer should also seek to understand and apply those musical principles of Gregorian Chant that have allowed it to serve its purpose so aptly. As expressed by the authors of the post-conciliar Church document, Musicam Sacram:

Musicians will enter on this new work with the desire to continue that tradition which has furnished the Church, in her divine worship, with a truly abundant heritage. Let them examine the works of the past, their types and characteristics, … so that “new forms may in some way grow organically from forms that already exist,” and the new work will form a new part in the musical heritage of the Church, not unworthy of its past.[1]

And furthermore:

Let them produce compositions which have the qualities proper to genuine sacred music, not confining themselves to works which can be sung only by large choirs, but providing also for the needs of small choirs and for the active participation of the entire assembly of the faithful.[2]

Along these same lines Pope Benedict XVI recently pointed out:

It is possible to modernize holy music, but this cannot happen outside the great traditional path of the past, of Gregorian chants and sacred polyphonic choral music… [3]

What are the “qualities proper to genuine sacred music” that need to be followed attentively in the composition and performance of new works? This is in fact a crucial question which requires much more space than the scope of this introduction would allow, in order to be answered adequately. However, a few first principles can be briefly articulated here:

- The human voice is always the primary instrument, and often the only instrument. Being an integral part of man, rather than his exterior creation, the voice has a unique capacity for intimate expression of the depth and breadth of human feeling and experience. It is equally accessible to all people and all cultures. When the organ or other instruments are used, it is for the purpose of supporting or enhancing, rather than dominating or supplanting, the voice.

- The rhythm of the music is united with the natural rhythm of the given sacred text, either through assuming the textual rhythm as its own, or by engaging in a gentle interplay with it. Any strong metrical or rhythmic effects that might overshadow the meaning of the text are avoided. With a few exceptions, Gregorian chant is characterized by a non-metered rhythm that allows great freedom in respecting the meaning and flow of the Word.

- Melodic lines and harmonies are carefully chosen to evoke dispositions and emotions that are appropriate to liturgical worship and interiority, and which steer clear of secular associations. This distinction is not meant in any way to demean the multifarious beauty that belongs to secular life and art, or to deny its transcendent dimension, but rather is meant to facilitate the flourishing of each - the sacred and the profane[4], divine worship and social intercourse - in its own proper time and place.

Authentic Artistry

It does not do justice to the nature of the Liturgy for its music to be merely correct, even according to the above-mentioned principles. In order for sacred music to reach its full stature, composers and musicians need to exercise true artistry, in which knowledge, inspiration, and skill all play a vital role.

Many may object here, saying that liturgical music is meant for “prayer rather than performance,” implying that prayer, being a humble, intimate communication with God, excludes or minimizes the need for artistry, which by its nature demands a focus on the externals of music-making. There is an element of truth in this, namely, that the relational dimension of the Liturgy is of immeasurably more importance than the artistic dimension. However, it is this very relational dimension which should motivate and empower composers and musicians as they devote all of their skill to create something as beautiful as possible for God, the Beloved. In addition, a certain level of artistry in composition and choral performance provides a foundation from which the other participants in the Liturgy can more fully interiorize the meaning of the words and more prayerfully join in the singing of their parts.

In the context of sacred music, compositional artistry will be manifested in gracefulness and dignity of melodic line, harmony, and dynamics, rather than in striking effects or grandiosity. The artistic performance of this music by cantors and choirs requires, among other things, diligent attention to precision of pitch and rhythm, natural resonance, lively and sensitive dynamics, appropriate tone quality, and clear diction. Qualities such as interiority and unity of sound among voices should preclude any harsh effects or displays of virtuosity, however appropriate these latter might be in other contexts.

Composers and performers of all kinds of music bear witness to the fact that the phenomenon of inspiration is a mysterious but important element in their creative process. How much more should the composer of sacred music, conscious of the dignity of the Liturgy, prayerfully seek that inspiration which will give his music a living, joyful, peaceful identity, beyond the mere notes on the musical score? When this gift is skillfully cultivated, choirs and congregations can in their turn participate in an experience of inspired beauty, which is directed toward the praise and glory of God.

Noble Accessibility

One of the clearest messages from the Second Vatican Council to composers of sacred music, was the need to create music that would facilitate the “full, conscious, and active” participation of the faithful:

In the restoration and promotion of the sacred liturgy, this full and active participation by all the people is the aim to be considered before all else, for it is the primary and indispensable source from which the faithful are to derive the true Christian spirit…[5]

How can music help to achieve this goal, while faithfully maintaining the other foundational qualities listed above? On the one hand, unceasing and genial efforts should be made to help priests and lay people to re-discover the great traditions of sacred music that are in fact their rightful patrimony. Too often this heritage has been ignored or rejected on the false premise that it is no longer relevant to modern man. On the other hand, the legitimate development of culture, as well as the authorized use of the vernacular in the Liturgy, beg for the conception of worthy new music to accompany both Latin and translated Liturgical texts. And in order for this music to fulfill its purpose, it needs to be imbued with a noble accessibility that allows it to be not only admired, but also deeply welcomed by “ordinary” people so as to become a fitting and authentic expression of their faith.

When this quest for full participation has been separated from the need for true sacred character and authentic artistry in liturgical music, as has often been the case over the decades since Vatican II, the results have been deeply disturbing for those sensitive to the musical, psychological and spiritual dimensions of the Mass. As world-renowned maestro Riccardo Muti recently observed:

The history of great music was determined by what the Church did. When I go to church and I hear four strums of a guitar or choruses of senseless, insipid words, I think it's an insult… I can't work out how come once upon a time there were Mozart and Bach and now we have little sing-songs. This is a lack of respect for people's intelligence. [6]

This interview, in which Muti praised the efforts of Pope Benedict to promote a renewal of sacred music, was a tremendous encouragement to me in my composition of the Mass of St. Philip Neri. He speaks authoritatively on behalf of all great musicians and all devout Catholics when he pleads for the renewal of sacred music in the Church’s Liturgy. At the same time he understands the need for accessibility:

Rather than obsess over creating masterpieces, contemporary composers should “prepare the future for a new language in the world of music - not one but several languages - that are more closely connected to the needs of people.” [7]

In searching for compositional models that do integrate sacred character, authentic artistry, and noble accessibility, I have in fact found two wonderful sources of inspiration. The first is the harmonized liturgical chant of the Russian Orthodox Church, developed by composers such as Smolensky, Chesnokov, and Rachmaninoff. The second is the music of Jacques Berthier written for the ecumenical Taizé Community in France, which has brought an elegant simplicity and power to the singing of sacred texts by very large groups of people. In each of these cases, composers with highly sophisticated skills have deliberately set aside the kind of harmonic and rhythmic complexity appropriate to the concert hall, in order to bring intense depth and beauty to simpler forms that thus become nobly accessible to “common” people from a wide variety of backgrounds. Both of these sources have been my constant companions in the composition of this musical setting of the Mass.

St. Philip Neri

I have chosen to name this work in honor of Philip Neri, because his life and apostolate, which effected such a great spiritual and cultural renewal in 16th century Rome, have also been an ongoing inspiration to me and the choirs that I have had the privilege of directing. Through his Oratory movement, which combined prayer, study, works of mercy, joyful fellowship, and the cultivation of the arts, he became a patron to great composers such as Palestrina and Animuccia. Influenced by the contagious holiness and joy of St. Philip, they were able to create a magnificent new repertoire of sacred polyphony, rooted in the ancient tradition of Gregorian chant, but also responding to the new needs and inspirations of their day. My hope and prayer is that the Mass of St. Philip Neri might be one small flame in a similarly authentic renewal of sacred music, faith and culture that is so needed in the Catholic Church today!

Paul Jernberg Clinton, Massachusetts February 24, 2012

You shall sprinkle me, listen here

[1] Musicam Sacram, Art. 59; quote from Sacrosanctum Concilium, Art. 23

[2] Sacrosanctum Concilium, Art. 121

[3] Comments by Pope Benedict during a concert conducted by Dominico Bartolucci, June 24, 2006.

[4] The word ‘profane’ here is used in its first meaning, which is ‘outside the temple’ (Gr. pro - fanus).

[5] Sacrosanctum Concilium, Art. 14

[6] Riccardo Muti interview with ANSA.IT, May 27, 2011

[7] John von Rhein interview with Muti in the Chicago Tribune, January 29, 2012