In-your-face with the Holy Face! Bearing witness to the Faith through a lapel pin with an icon of Christ!

The Christian Mission to Evangelize American Culture

An Organization to Watch - The St Louis IX Art Society in Southern Louisiana

They have a vision of a liturgically oriented focus on sacred art, that encourages experimentation outside the church and a conservative approach within it. They have a long view. Nobody involved thinks they are the finished product. All are looking to develop and improve and teach the next generation. They have a 50 year time frame.

Does it really matter what Pixar do? Lighten up, it's just a children's movie...

Thanks to Rick, whoever you are for your comment on the review of Inside Out, posted on August 17th. I responded to it in the comments page, but I think his simple remarks highlight some good discussion points that are worthy of wider consideration. Is the film industry important? Am I just over analyzing an innocent children's film?

Thanks to Rick, whoever you are for your comment on the review of Inside Out, posted on August 17th. I responded to it in the comments page, but I think his simple remarks highlight some good discussion points that are worthy of wider consideration. Is the film industry important? Am I just over analyzing an innocent children's film?

Here is Rick's comment, he first pulls a quote out of my blogpost:

Here is Rick's comment, he first pulls a quote out of my blogpost:

' "No wonder Riley was struggling with life, she was living in miserable isolation! May the Lord be with your spirit." Just a thought, you might want to know that Riley is not real. It's just a movie mate, take it easy. There are bigger battles to fight.'

And here is my reaction. First the quick reply to this is: '...And this is just a movie review Rick, and that line you quoted was a joke! Lighten up and take it easy yourself…mate .'

But there is a serious point here and in this I am not joking. In what was an entertaining film (although by Pixar’s high standards I would say only moderately entertaining) is the propagation of a false worldview. How important you think this is depends on how influential you think that such film will be. As a general point I would say that clearly certain parts of the film industry take it very seriously because they go to great lengths to engage the mass population with films that reinforce a false worldview in so many aspects – faith, morals, and attitude to the environment, for example. I would say that they have doing this very very successfully over the last 50 years particularly. This can be done sometimes subtly – as with this film – and sometimes more stridently.

For good or ill, popular culture both reflects and propagates a worldview as powerfully as any essay in an academic journal. If we do not like the wider culture, we cannot disengage from the culture, even if we wanted to. Even the most cloistered monk is product of the greater society of which he is part. The question is not whether or not to engage, therefore, but how do we engage? Are we going to do it well, or badly? How can we transform it so that it becomes one of truth and beauty?

For good or ill, popular culture both reflects and propagates a worldview as powerfully as any essay in an academic journal. If we do not like the wider culture, we cannot disengage from the culture, even if we wanted to. Even the most cloistered monk is product of the greater society of which he is part. The question is not whether or not to engage, therefore, but how do we engage? Are we going to do it well, or badly? How can we transform it so that it becomes one of truth and beauty?

Speaking generally, without having any particular film in mind, the degree of misery and death that results from the propagation of a false psychology, or false morality, or a false environmentalism, or falsity of any form, is immeasurable (I do not exaggerate on this, see my posting on environmentalism next week), and that is what I care about. I am not suggesting that every film is a cynical attempt to manipulate. Very often it is an innocent and well meaning effort to entertain and make money (not bad things in themselves), by appealing to and reflecting the attitudes that it believes its market already has. When the seemingly innocuous presentations are taken to their logical conclusion, however, regardless of motives, the end result is the same in both cases.

The evangelization of the culture is the battle we must engage in and I would say that there are fewer battles that are more important or bigger.

The evangelization of the culture is the battle we must engage in and I would say that there are fewer battles that are more important or bigger.

Believe it or not, in the 1930s Pius XI praised Hollywood for the influence of the its films on society. However well or badly I am doing it, my motivation in doing a review like this is to try to encourage Christian filmmakers to be involved again and start propagating a worldview that will actually promote the general happiness and harmony in society and ultimately, the salvation of souls. I want to see them engaging as skillfully, as subtly and as engagingly as the secular materialists have been doing in film, music and all aspects of the popular culture. I am not thinking of in-your-face accounts of the gospel, so much as films like Inside Out, which are so engaging that they draw in and influence people without resistance.

Family films and films for children, incidentally, are an important battleground in this context for two reasons: first, as the Jesuits used to say, give the child and I'll give you the man. Children are the most easily influenced at will grow up to make future society reflect what they believe. Second, few children watch these movies on their own. There are usually adults with them. One of the ways of making these films so popular is to make them appeal simultaneously at different levels. They are designed to engage the adults too. If the parents are entertained also, then they are more likely to want to take their children to the film. This need to build in a dual appeal means that the genre automatically engages the creators philosophically - they have to be able to think about concepts at different levels; and it is what makes children's entertainment simultaneously some of the most sophisticated, engaging and powerful there is. At the root of every story are some assumed facts, premises about the nature of reality that govern the logic of the progression of the story and make it either convincing or not as the case may be. This is inescapable. If we ignore this then we risk inadvertently promoting falsity. If we use it, we can create a beautiful, wonderful, entertaining and stimulating culture that influences for the good.

Family films and films for children, incidentally, are an important battleground in this context for two reasons: first, as the Jesuits used to say, give the child and I'll give you the man. Children are the most easily influenced at will grow up to make future society reflect what they believe. Second, few children watch these movies on their own. There are usually adults with them. One of the ways of making these films so popular is to make them appeal simultaneously at different levels. They are designed to engage the adults too. If the parents are entertained also, then they are more likely to want to take their children to the film. This need to build in a dual appeal means that the genre automatically engages the creators philosophically - they have to be able to think about concepts at different levels; and it is what makes children's entertainment simultaneously some of the most sophisticated, engaging and powerful there is. At the root of every story are some assumed facts, premises about the nature of reality that govern the logic of the progression of the story and make it either convincing or not as the case may be. This is inescapable. If we ignore this then we risk inadvertently promoting falsity. If we use it, we can create a beautiful, wonderful, entertaining and stimulating culture that influences for the good.

Just to redress the balance, here is a Pixar movie I loved (and, I'm going to admit it, I saw it on my own, as an adult and went to see it twice!).

— ♦—

My book the Way of Beauty is available from Angelico Press and Amazon.

—JAY W. RICHARDS, Editor of the Stream and Lecturer at the Business School fo the Catholic University of America said about it: “In The Way of Beauty, David Clayton offers us a mini-liberal arts education. The book is a counter-offensive against a culture that so often seems to have capitulated to a ‘will to ugliness.’ He shows us the power in beauty not just where we might expect it — in the visual arts and music — but in domains as diverse as math, theology, morality, physics, astronomy, cosmology, and liturgy. But more than that, his study of beauty makes clear the connection between liturgy, culture, and evangelization, and offers a way to reinvigorate our commitment to the Good, the True, and the Beautiful in the twenty-first century. I am grateful for this book and hope many will take its lessons to heart.”

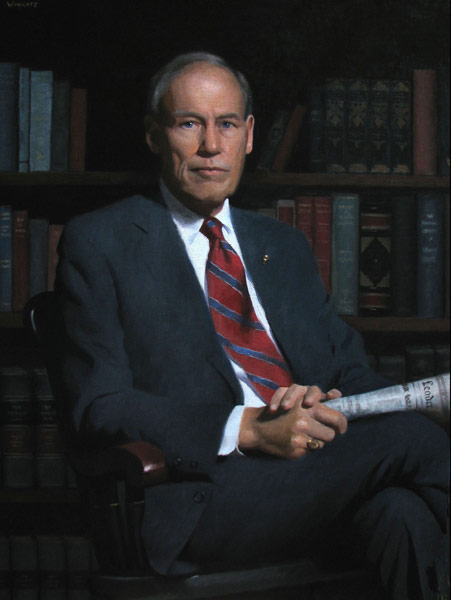

Some More about Henry Wingate, his work and the traditional style he paints in

Continuing in the tradition of the Boston School of portraitists, and the baroque.

Following on from the last post, I thought that readers might be interested to see some more work of artist Henry Wingate, and to know more about the academic method that he uses to such great effect. I like his portraits especially and he is one of relatively few artists around today who is making a real contribution to a re-establishment of traditional principles by teaching as well as painting (motivated by a desire to serve the Church).

Continuing in the tradition of the Boston School of portraitists, and the baroque.

Following on from the last post, I thought that readers might be interested to see some more work of artist Henry Wingate, and to know more about the academic method that he uses to such great effect. I like his portraits especially and he is one of relatively few artists around today who is making a real contribution to a re-establishment of traditional principles by teaching as well as painting (motivated by a desire to serve the Church).

Based in rural Virginia, Wingate studied with Paul Ingbretson in New England and with Charles Cecil, in Florence, Italy. Both Ingbretson and Cecil studied under R H Ives Gammell, the teacher, writer, and painter who perhaps more than anyone else kept the traditional atelier method of painting instruction alive.

The academic method was first developed in Renaissance Italy and was the basis of transmission of the baroque style (described by Pope Benedict XVI as one of three authentically Catholic liturgical artistic traditions, along with the gothic and the iconographic). The method is named after the art academies of the seventeenth century. The most famous early Academy was opened by the Carracci brothers, Annibali, Agostino, and Ludivico, in Bologna in 1600. Their method became the standard for art education and nearly every great Western artist for the next 300 years received, in essence, an academic training.

Under the influence of the Impressionists the method almost died out. They consciously broke with tradition and refused to pass it on to their pupils. This is strange given that all the well known Impressionists were themselves academically trained, used the skills they learned in their art and in fact could not have produced the paintings they did without it. By 1900 the grand academies of Europe had closed. The fact that it survives at all is largely the legacy of the Boston group of figurative artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most prominent among them John Singer Sargent (who was trained in Paris, but knew them and mixed with them). Other names are Joseph de Camp, Edmund Tarbell and Emil Grundmann. The US was slower to adopt the destructive ideas of Europe and the traditional schools survived there a little longer. Ives Gammell received his training at Boston Museum of Fine Arts in the years just before the First World War. The most well know ateliers that exist today in the US and Italy, were opened by artists who trained under Gammell in the 1970s (when he was in his 80s). Most of people painting and teaching in this style today, that I know of, come out of this line.

Under the influence of the Impressionists the method almost died out. They consciously broke with tradition and refused to pass it on to their pupils. This is strange given that all the well known Impressionists were themselves academically trained, used the skills they learned in their art and in fact could not have produced the paintings they did without it. By 1900 the grand academies of Europe had closed. The fact that it survives at all is largely the legacy of the Boston group of figurative artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most prominent among them John Singer Sargent (who was trained in Paris, but knew them and mixed with them). Other names are Joseph de Camp, Edmund Tarbell and Emil Grundmann. The US was slower to adopt the destructive ideas of Europe and the traditional schools survived there a little longer. Ives Gammell received his training at Boston Museum of Fine Arts in the years just before the First World War. The most well know ateliers that exist today in the US and Italy, were opened by artists who trained under Gammell in the 1970s (when he was in his 80s). Most of people painting and teaching in this style today, that I know of, come out of this line.

The ateliers of the 19th century had become detached from their Christian ethos and the sacred art of the period was inferior to that of the period 200 years before. However, portraiture, and especially that of the Sargent and the Boston School retained the principles of the balance of sharpness and focus, the variation in colour intensity and the contrast in light and dark that characterized the baroque. Today, even portraiture has declined (Wingate and his ilk being exceptions to this) because very often it is based upon photographic images rather than observation from nature. Photographs reflect the distortion of the lens of the camera, which is different from that of the eye; they have too many sharp edges and everywhere is both highly detailed and highly coloured. Consider, for example, how Wingate has handled the drapery in the portrait at the top, left. He has not supplied a fully detailed rendering, yet there is not a sense of a lack of detail because when we look at the figure, which is what Wingate wants us to look at, the detail supplied is sufficient for our peripheral vision.

The ateliers of the 19th century had become detached from their Christian ethos and the sacred art of the period was inferior to that of the period 200 years before. However, portraiture, and especially that of the Sargent and the Boston School retained the principles of the balance of sharpness and focus, the variation in colour intensity and the contrast in light and dark that characterized the baroque. Today, even portraiture has declined (Wingate and his ilk being exceptions to this) because very often it is based upon photographic images rather than observation from nature. Photographs reflect the distortion of the lens of the camera, which is different from that of the eye; they have too many sharp edges and everywhere is both highly detailed and highly coloured. Consider, for example, how Wingate has handled the drapery in the portrait at the top, left. He has not supplied a fully detailed rendering, yet there is not a sense of a lack of detail because when we look at the figure, which is what Wingate wants us to look at, the detail supplied is sufficient for our peripheral vision.

If you go somewhere where you can see a series of portraits painted over long period (perhaps those of the principals hanging in the dining hall of a long-established school or college - I recently went to a dinner at the Roxbury Latin School in Boston - founded in the 17th century), you can see this difference between the traditional and the modern portraits very easily.

those of the principals hanging in the dining hall of a long-established school or college - I recently went to a dinner at the Roxbury Latin School in Boston - founded in the 17th century), you can see this difference between the traditional and the modern portraits very easily.

I am not against photographic portraits by the way, far from it. The point is that it is a different medium to painting, to which we respond differently. These Christian considerations can be communicated through photography, in my opinion, but they have to be done differently. (And if there are any photographers out there, I think that relating the art of photography to the Christian tradition of visual imagery is an area that has not yet been properly developed.) The point here is that paintings made from photographs rarely work unless the artist is conscious of these stylistic considerations and has the skill and experience to adapt what the photographic information.

The retention of these principles in 19th-century portrait painting was not due to a Christian motivation, to my knowledge. If a portrait painter is to make a living then he cannot indulge in the free expression that one might see in other forms. The portrait painter, Christian or not, must seek to balance two things. First, he must produce a painting that is attractive to those who are going to see it, usually the individual and those who know him or her. The usual approach to this is to bring out the best human characteristics of the person. He is ennobling - idealizing - the individual. However, he cannot take this too far and go beyond the bounds of truth. He must also capture the likeness of the individual otherwise it will not be recognized as a portrait. My teacher in Florence, Charles Cecil, taught us not to be bound by an absolute standard of visual accuracy, but to modify what we saw, slightly. We were told to stray ‘towards virtue rather vice’: strengthen the chin slightly, for example. This approach is consistent with the Christian artist’s portrayal of a person, which is as much about revealing what a person can be, as what he is. The idea that the crucial aspect by which the artist reveals the person is by capturing the likeness goes back to St Theodore the Studite, the Church Father whose theology settled the iconoclastic controversy in the 9th century.

For the work of Henry Wingate, see www.henrywingate.com.

A Model for A Cultural Center for the New Evangelization

Going Local for Global Change.

How About a Chant Cafe with Real Coffee ..and Real Chant?

Going Local for Global Change.

How About a Chant Cafe with Real Coffee ..and Real Chant?

There is a British comedienne who in her routine adopted an onstage persona of a lady who couldn't get a boyfriend and was very bitter about it (although in fact as she became a TV personality beyond the comedy routines, she revealed herself as a naturally engaging and warm character who was in fact happily married with a child). Jo Brand is her name and she used to tell a joke in which she said: 'I'm told that a way to a man's heart is through his stomach. I know that's nonsense - guys will take all the food you give them but it doesn't make them love you. In fact I'll tell you the only certain way to man's heart...through the rib cage with a bread knife.' Well wry humour aside, I think that in fact there is more truth to the old adage than Jo Brand would have acknowledged (on stage at least). Perhaps we can touch people's hearts in the best way through food and drink, and in particular coffee.

There is a coffee shop in Nashua NH where I live called Bonhoeffer's. It is the perfect place for conversation. They have designed it so that people like to sit and hang out - pleasing decor, free wifi, and different sitting arrangements, from pairs of cozy arm chairs to highbacked chairs around tables. The staff are personable and it is roomy enough that they can place clusters of chairs and sofas that are far enough apart so that you don't feel that you are eavesdropping on your neighbors' conversation; and close enough together that you feel part of a general buzz of conversation around you. There is not an extensive food menu but what they have is good and goes nicely with the image it conveys of coffee and relaxed conversation - pastries, a slice of quiche or crepes for example. It has successfully made itself a meeting place in the town because of this.

This is all very well and good, if not particularly remarkable. But, you wouldn't know unless you recognized the face of the German protestant theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer in the cafe logo and started to ask questions, or noticed and took the time to read the display close the door as you are on your way out, that it is run by the protestant church next door, Grace Fellowship Church. Furthermore a proportion of turnover goes towards supporting locally based charities around the world - they list as examples projects in the Ukraine, Myanmar, Ethiopia, Haiti and Jamaica on their website. Talks and events linked to their faith are organised and there are pleasant well equipped meeting rooms available for hire. I include the logo and website to illustrate my points, but also in the hope that if Bonhoeffer's see this they might push an occasional free coffee in my direction...come on guys!

Well, it was worth a try. Anyway, back to more serious things...the presentation of their mission does not even dominate the cafe website which talks more about things such as the beans they use in their coffee, prices and opening times and the food menu. The most eye-catching aspect when I was nosing around is the announcement of the new crepes menu! There is one tab that has the heading Hope and Life Kids and when you click it it takes you through to a dedicated website of that name, here , which talks about the charity work that is done.

I went into Bonhoeffer's recently with Dr William Fahey, the President of Thomas More College, just for cup of coffee and a chat, of course, and he remarked to me as we sat down that this is the sort of the thing that protestants seem to be able to organize; and how we wished he saw more Catholics doing the same thing.

I agree. What the people behind this little cafe had done was to create a hub for the local community that has an international reach. It is at once global and personal. I would like to see exactly what they have done replicated by Catholics. But, crucially, good though it is I would add to it, and make it distinctly Catholic so that it attracts even more coffee drinkers and then can become a subtle interface with the Faith, a focus for the New Evangelization in the neighborhood.

I agree. What the people behind this little cafe had done was to create a hub for the local community that has an international reach. It is at once global and personal. I would like to see exactly what they have done replicated by Catholics. But, crucially, good though it is I would add to it, and make it distinctly Catholic so that it attracts even more coffee drinkers and then can become a subtle interface with the Faith, a focus for the New Evangelization in the neighborhood.

I don't know how to run coffee shops, so I would be happy with a first step that copied precisely theirs - the establishment of coffee shop that competes with all others in doing what coffee shops are meant to do, sell coffee. Then I would offer through this interface talks and classes that transmit the Way of Beauty, many of which are likely to have an appeal to many more than Catholics (especially those with a 'new-age spiritual' bent). There are a number that come to mind that attract non-Christians and can be presented without compromising on truth - icon painting classes; or 'Cosmic Beauty' a course in traditional proportion in harmony based upon the observation of the cosmos; or praying with the cosmos - a chant class that teaches people to chant the psalms and explains how the traditional pattern of prayer conforms to cosmic beauty.

A yoga class that has the word yoga but is simply a adoption of the physical aspects would attract people who are open to spirituality. Yoga is very successful in turning people with no previous inclination to the spiritual to Eastern spirituality - so why not offer Christian mediation/contemplative prayer and incorporate this into the instruction. I once had discussions with a Dominican about the known prayer postures of St Dominic. He showed me some stick figure diagrams he had drawn to represent them. He thought that these could be the basis for a Christian yoga that engages people spiritually through a focus on the physical. I don't know if he was right, but something on these lines would be good.

Another way of engaging people who are then going to be open to mediation, chant and retreats is to have 12-step fellowship groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous meeting closeby. I am aware of several priests who go to AA and also many converts to Catholicism who were first given a faith in God through such groups. The 12 steps are a systematic application of Christian principles (without reference to the Church). The non-demoninational character of the groups does mean that people can be misdirected towards other faiths in their search, but if we were present to provide an attractive picture of the Faith, it would attract interest I am sure.

Another class that might engage people is a practical philosophy class that directs people towards the metaphysical and emphasizes the need of all people to lead a good life and to worship God in order to be happy and feel fulfilled. This latter part is vital for it is the practice of worship that draws people up from a lived philosophy into a lived theology and ultimately to the Faith. For it is only once experienced that people become convinced and want more. This works. When I was living in London I used to see advertisements in the Tube for a course in practical philosophy. These were offered by a group that had a modern 'universalist' approach to religion in which they saw each great 'spiritual tradition' as different cultural expressions of a single truth that were equally valid. The adverts however, did not mention religion at all but talked about the love and pursuit of universal wisdom that looked like a new agey mix of Eastern mysticism and Plato. The content of the classes, they said, was derived from the common experience of many if not all people and from it one could hope to lead a happy useful life. They had great success in attracting educated un-churched professionals not only to attend the class, but also to go in to attend more classes and ultimately to commit their lives to their recommended way of living. They were also prepared to donate generously - this is a rich organisation. Their secret was the emphasis on living the life that reason lead you to and not require, initially at least a commitment to formal religion. Most became religious in time, which ultimately lead some to convert to Christianity - although many, because of the flaws in the opening premises and the conclusion this lead to, were lead astray too. It was by meeting some of these converts that I first heard about it. There is room, I think, for a properly worked out Catholic version of this.

Another class that might engage people is a practical philosophy class that directs people towards the metaphysical and emphasizes the need of all people to lead a good life and to worship God in order to be happy and feel fulfilled. This latter part is vital for it is the practice of worship that draws people up from a lived philosophy into a lived theology and ultimately to the Faith. For it is only once experienced that people become convinced and want more. This works. When I was living in London I used to see advertisements in the Tube for a course in practical philosophy. These were offered by a group that had a modern 'universalist' approach to religion in which they saw each great 'spiritual tradition' as different cultural expressions of a single truth that were equally valid. The adverts however, did not mention religion at all but talked about the love and pursuit of universal wisdom that looked like a new agey mix of Eastern mysticism and Plato. The content of the classes, they said, was derived from the common experience of many if not all people and from it one could hope to lead a happy useful life. They had great success in attracting educated un-churched professionals not only to attend the class, but also to go in to attend more classes and ultimately to commit their lives to their recommended way of living. They were also prepared to donate generously - this is a rich organisation. Their secret was the emphasis on living the life that reason lead you to and not require, initially at least a commitment to formal religion. Most became religious in time, which ultimately lead some to convert to Christianity - although many, because of the flaws in the opening premises and the conclusion this lead to, were lead astray too. It was by meeting some of these converts that I first heard about it. There is room, I think, for a properly worked out Catholic version of this.

Along a similar line are classes that help people to discern their personal vocation, again using traditional Catholic methods. Once we discover this then we truly flourish. God made us to desire Him and to desire the means by which we find Him. While the means by which we find Him is the same in principle for each of us, we are all meant to travel a unique path that is personal to us. To the degree that we travel this path, the journey of life, as well as its end, is an experience of transformation and joy.

Along a similar line are classes that help people to discern their personal vocation, again using traditional Catholic methods. Once we discover this then we truly flourish. God made us to desire Him and to desire the means by which we find Him. While the means by which we find Him is the same in principle for each of us, we are all meant to travel a unique path that is personal to us. To the degree that we travel this path, the journey of life, as well as its end, is an experience of transformation and joy.

Drawing on people from the local Catholic parishes I would hope to start groups that meet for the singing of an Office - Vespers and or Compline or Choral Evensong and fellowship on a week night; and have talks on the prayer in the home and parish as described by the The Little Oratory. This book was intended as a manual for the spiritual life of the New Evangelization and would ideally be one that supports the transmission of practices that are best communicated by seeing, listening and doing. These weekly 'TLO meetings' would be the ideal foundation for learning and transmitting the practices. They would be very likely a first point of commitment for Catholics who might then be interested in getting involved in other ways. It would enable them also to go back to their families and parishes teach any others there who might be interested to learn.

Drawing on people from the local Catholic parishes I would hope to start groups that meet for the singing of an Office - Vespers and or Compline or Choral Evensong and fellowship on a week night; and have talks on the prayer in the home and parish as described by the The Little Oratory. This book was intended as a manual for the spiritual life of the New Evangelization and would ideally be one that supports the transmission of practices that are best communicated by seeing, listening and doing. These weekly 'TLO meetings' would be the ideal foundation for learning and transmitting the practices. They would be very likely a first point of commitment for Catholics who might then be interested in getting involved in other ways. It would enable them also to go back to their families and parishes teach any others there who might be interested to learn.

We could perhaps sell art by making it visible on the walls or have a permanent, small gallery space adjacent to the sitting area (provided it was good enough of course - better nothing at all than mediocre art!). All would available in print form online as well of course, just as talks could be made available much more widely and broadcasted out across the net if there was interest. This is how the local becomes global.

What I am doing here is taking the business model of the cafe and combining it with the business model of the Institute of Catholic Culture which is based in Arlington Diocese in Virginia. I wrote about the great work of Deacon Sabatino and his team at the ICC in Virginia in an article here called An Organisational Model for the New Evangelization - How To Make it At Once Personal and Local, and have International Recognition. His work is focussed on Catholic audiences, and is aimed predominently at forming the evangelists, rather than reaching those who have not faith (although I imagine some will come along to their talks). By having an excellent program and by taking care to ensure that his volunteers feel involved and are appreciated and part of a community (even organising special picnics for them) Deacon Sabatino has managed to get hundreds volunteering regularly.

Another group that does this just well is the Fra Angelico Institute for Sacred Arts in Rhode Island run by Deacon Paul Iacono. I have written about his great work here. The addition of a coffee shop give it a permanent base and interface with non-Catholics and even the non-churched.

I would start in a city neighborhood in an area with a high population and ideally with several Catholic parishes close by that would provide the people interested in attending and be volunteers and donors helping the non-coffee programs. It always strikes me that the Bay Area of San Francisco, especially Berkeley, is made for such a project. There is sufficiently high concentration of Catholics to make it happen, a well established cafe culture; and the population is now so far past 'post-Christian' that there is an powerful but undirected yearning for all things spiritual that directs them to a partial answer in meditation centers, wellness groups, spiritual growth and transformation classes, talks on reaching for your 'higher self' and so on. Many are admittedly hostile to Christianity, but they seek all the things that traditional, orthodox Christianity offers in its fullness although they don't know it. Provided that they can presented with these things in such a way that it doesn't arouse prejudice, they will respond because these things meet the deepest desire of every person.

I would start in a city neighborhood in an area with a high population and ideally with several Catholic parishes close by that would provide the people interested in attending and be volunteers and donors helping the non-coffee programs. It always strikes me that the Bay Area of San Francisco, especially Berkeley, is made for such a project. There is sufficiently high concentration of Catholics to make it happen, a well established cafe culture; and the population is now so far past 'post-Christian' that there is an powerful but undirected yearning for all things spiritual that directs them to a partial answer in meditation centers, wellness groups, spiritual growth and transformation classes, talks on reaching for your 'higher self' and so on. Many are admittedly hostile to Christianity, but they seek all the things that traditional, orthodox Christianity offers in its fullness although they don't know it. Provided that they can presented with these things in such a way that it doesn't arouse prejudice, they will respond because these things meet the deepest desire of every person.

Here's the additional element that holds it all together. As well as the workshops or classes I have mentioned I would have the Liturgy of the Hours prayed in a small but beautiful chapel adjacent to and accessible from the cafe on a regular basis, ideally with the full Office sung. The idea is for people in the cafe to be aware that this is happening, but not to feel bound to go or guilty for not doing so. I thought perhaps a bell and announcement: 'Lauds will be chanted beginning in five minutes in the chapel for any who are interested.' Those who wish to could go to the chapel and pray, either listening or chanting with them. The prayer would not be audible in the cafe. So those who were not interested might pause momentarily and then resume their conversations.

From the people who attend the TLO meetings I would recruit a team of volunteers might volunteer to sing in one or more extra Offices during the week if they could. If you have two people together, meeting in the name of Jesus, they can sing an Office for all. The aim is to have the Office sung on the premises give good and worthy praise to God for the benefit of the customers, the neighbourhood, society and the families and groups that each participates in aside from this and for the Church.

When the point is reached that the Office is oversubscribed, we might encourage groups to pray on behalf of others also in different locations by, for example singing Vespers regularly in local hospitals or nursing homes. I describe the practice of doing this in an appendix in The Little Oratory and in a blog post here: Send Out the L-Team, Making a Sacrifice of Praise for American Veterans.

As this grows, the temptation would be to create a larger and larger organization. This would be a great error I think. The preservation of a local community as a driving force is crucial to giving this its appeal as people walk through the door. There is a limit to how big you can get and still feel like a community. Like Oxford colleges, when it gets to big, you don't grow into a giant single institution, but limit the growth and found a new college. So each neighborhood could have its own chant cafe independently run. There might be, perhaps a central organization that offers franchises in The Way of Beauty Cafes so that the materials and knowledge needed to make it a success in your neighborhood are available to others if they want it.

I have made the point before that eating and drinking are quasi-liturgical activities by which we echo the consuming of Christ Himself in the Eucharist (it is not the other way around - the Eucharist comes first in the hierarchy). So it should be no surprise to us that food and drink offered with loving care and attention open up the possibilities of directing people to the love of God. If the layout and decor are made appropriate to that of a beautiful coffee shop and subtly and incorporating traditional ideas of harmony and proportion, and colour harmony then it will be another aspect of the wider culture that will stimulate the liturgical instincts of those who attend. (I have described how that can be done in the context of a retail outlet in an appendix of The Little Oratory.) We should bare in mind Pope Benedict's words from Sacramentum Caritatis (71):

'Christianity's new worship includes and transfigures every aspect of life: "Whether you eat or drink, or whatever you do, do all to the glory of God." (1Cor 10:13) Here the instrinsically eucharistic nature of Christian life begins to take shape. The Eucharist, since it embraces the concrete, everyday existence of the believer, makes possible, day by day, the progressive transfiguration of all those called by grace to reflect the image of the Son of God (cf Rom 8:29ff). There is nothing authentically human - our thoughts and affections, our words and deeds - that does not find in the sacrament of the Eucharist the form it needs to be lived in the full.'

So Jo Brand, we'll put away the bread knife and offer the bread instead!

Step one seems to be...first get your coffee shop. Anyone who thinks they can help us here please get in touch and we'll make it happen!

Creating the New Culture of Beauty - a little parish in Jasper, Georgia shows us the way

The artistic and musical creativity of a parish shows us why liturgical and, hence, cultural renewal is likely to be a grass-roots, bottom-up process. If you want to know how your parish can do it, read this. Who is going to patronize, ie pay for, the new works that will the Catholic culture? Will it be committees created by the Vatican? Unlikely, given the evidence of the past 50 years or so. Will it be those who fund the grand cathedrals in our large cities? Possibly, but again the evidence of the recent past is not too encouraging there (although not altogether hopeless). How about the ordinary parish church? I think probably the latter. The sheer statistics point to it. There is no reason to believe that a parish priest or parish community is going to be any less (or more) aware of Catholic cultural traditions than those of cathedrals. But given that there are more parishes than cathedrals, says it is more likely that the first green shoots of cultural recovery are going to happen at the local level.

The obvious objection to this is money - where will parishes get the money to patronise the liturgical arts? Don't you need the sort of money that those who build cathedrals have to pay the artists well? I would say no. First, I do believe that artists ought to be paid at least the hourly rate we would pay any other artisan for his work (think of how much a plumber charges) which would ensure a decent price for a picture. But I say also that if the will is there it can pay for art. If a church can afford to keep the plumbing and its roof in good order; it can afford to pay reasonable prices for art and music.

I have two heartening stories about ordinary parish churches having the interest to do great work. The first is the subject of this week's story and is in Jasper, Georgia. The second is a little church in Wyoming that has decided to install a full cosmati pavement in its floor, to replace the carpeting that was there previously. I will give more detail about the second on another occasion. But today Our Lady of the Mountains, Jasper, Georgia, set, as the name suggest up in the hills, the blueridge North Georgia mountains.

I have just been contacted by Fr Charles Byrd the paster who informed me that the church had commissioned and original piece of music for their Good Friday liturgy. I'll let him tell you some detail:

'On Good Friday, 18 April 2014, at the close of Communion, the St. Gregory Choir of Our Lady of the Mountains Catholic Church in Jasper, Georgia, with soloist, Mr. Joseph McBrayer, and organist, Mr. Joseph D’Amico, under the direction of Mrs. Bridget Scott, performed for the first time ever The Song of Rood. Our relic of the True Cross, which the congregation had just venerated, was enthroned upon the altar. This recording documents that first performance. The parish had commissioned this music from Mr. Dallas Gambrell with the text loosely based upon a portion of Saint Caedmon’s epic poem, The Dream of the Rood, one of the oldest, if not the oldest, Christian texts written in English. St. Caedmon was a 7th / 8th century herdsman, lay brother, and poet, and is considered the Father of English Sacred Song. The section we used for the anthem is that part of his longer poem that had been carved in runes on the Ruthwell Cross (or rood), a standing preaching cross, in what is today southwest Scotland.'

It was sung after the Reproaches and Communion and Fr Charles tells me, may be used for the Exaltation of the Cross. You can read more about this and hear the recording of the piece (which I like very much) on their website here.

This is the same parish that contacted me and was looking to commission four icons (they commissioned two from me in the end and I referred them to another iconographer for the other two). What was noticeable to me in undertaking these is how knowledgeable and helpful he was as a patron. He had a firm idea of what he wanted, had done all the background reading on the appearances of the two saints - Ambrose and Gregory - and was clear in his mind why he wanted new images. He was open to suggestions from me as to how we might conform to his idea. As this discussion was taking place I was reminded of John Paul II's call, in his Letter to Artists, of a 'renewed dialogue' between artists and the Church. How did JPII imagine this dialogue would play out, one wonders. I can't answer that, but my own part, I don't think this is something that is going to happen at an institutional level or at grand conferences in Rome. Rather, it will right at the grassroots, where priest and congregation talk to artist and between them they produce something that will be used regularly by those who are commissioning. The great thing about the modern age is that technology, such as the internet (with media such as this blog!), ensure that remoteness does not mean isolation. Georgia and Wyoming can speak to world as easily as Rome or Washington.

Here we have someone with a great sense of the culture and the liturgy and this is what makes it. As a general rule, for a parish to be able to achieve this is needs a consensus on what is good, artistically and musically; or at least a well placed trust on the part of those who do not know, in those who do. That is the difficult part. If priest and congregation are at odds with each other it will reduce the chances of anything being done. Choosing art or music by committee which has to reconcile widely differing views by compromise, often leads to the worst of all both worlds, not the best.

Coming back to this commission: here is the description of their adaptation of the text for modern congregations: 'Our text, a modern adaptation, takes some liberties with Caedmon’s text. We augmented the text with some verses from the Vercelli Book to give this abridged poem more clarity. The original Anglo-Saxon text would be hard for us to understand today, but one phrase in that original tongue remains in our anthem — “Krist waes on rodi,” which means “Christ was on the cross.” There are two voices in the poem, the voice of the dreamer who narrates his vision, and the voice of the Holy Rood, who recalls the heroic struggle of the Crucifixion of the Lord. We can almost think of this song as a dramatic play. The chorus speaks for Caedmon and a soloist speaks the soliloquy of the Rood.

Chorus:

Hear now a vision long foretold of greatest hero from of old.

Naked He embraced the rood;

He was stripped upon the wood.

So the blessed Cross did say of Him who died for us that day.

Krist waes on rodi, Krist waes on rodi, Krist waes on rodi. Gloria.

Krist waes on rodi, Krist waes on rodi, Krist waes on rodi. Gloria.'

I give you images of the paintings commissioned from me which were delivered last Christmas as well as the recording of the music commissioned. I can't comment on the pictures (being mine) and I think the music is has the qualities of goodness of form, holiness and universality that are needed in liturgical music. Regardless, here is the point: even if you don't like what Our Lady of the Mountains has done, we can see from this example that this really can be a bottom up cultural transformation. It starts with inculturation in families and parishes who demand beautiful forms in unity with the liturgy, and beautiful worship. I don't know what the liturgy at Our Lady of the Mountains is like, but I'm guessing from the images and the music I have heard, that it is not dominated by guitars and tambourines.

From the fact that the number of parish churches is much greater

How to Make an Icon Corner

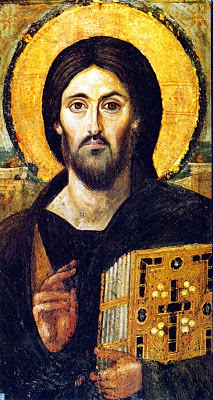

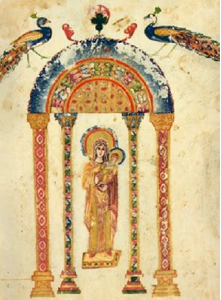

Beauty calls us to itself and then beyond, to the source of all beauty, God. God's creation is beautiful, and God made us to apprehend it so that we might see Him through it. The choice of images for our prayer, therefore, is important. Beautiful sacred imagery not only aids the process of prayer, but what we pray with influences profoundly our taste: praying with beautiful sacred art is the most powerful education in beauty that there is. In the end this is how we shape our culture, especially so when this is rooted in family prayer. The icon corner will help us to do that. I am using icon here in the broadest sense of the term, referring to a sacred image that depicts the likeness of the person portrayed. So one could as easily choose Byzantine, gothic or even baroque styles.

The contemplation of sacred imagery is rooted in man’s nature. This was made clear by the 7th Ecumenical Council, at Nicea. Through the veneration icons, our imagination takes us to the person depicted. The veneration of icons, therefore, is an aid to prayer first and it serves to stimulate and purify the imagination. This is discussed in the writings of Theodore the Studite (759-826AD), who was one of the main theologians who contributed to the resolution of the iconoclastic controversy.

Beauty calls us to itself and then beyond, to the source of all beauty, God. God's creation is beautiful, and God made us to apprehend it so that we might see Him through it. The choice of images for our prayer, therefore, is important. Beautiful sacred imagery not only aids the process of prayer, but what we pray with influences profoundly our taste: praying with beautiful sacred art is the most powerful education in beauty that there is. In the end this is how we shape our culture, especially so when this is rooted in family prayer. The icon corner will help us to do that. I am using icon here in the broadest sense of the term, referring to a sacred image that depicts the likeness of the person portrayed. So one could as easily choose Byzantine, gothic or even baroque styles.

The contemplation of sacred imagery is rooted in man’s nature. This was made clear by the 7th Ecumenical Council, at Nicea. Through the veneration icons, our imagination takes us to the person depicted. The veneration of icons, therefore, is an aid to prayer first and it serves to stimulate and purify the imagination. This is discussed in the writings of Theodore the Studite (759-826AD), who was one of the main theologians who contributed to the resolution of the iconoclastic controversy.

In emphasising the importance of praying with sacred images Theodore said: “Imprint Christ…onto your heart, where he [already] dwells; whether you read a book about him, or behold him in an image, may he inspire your thoughts, as you come to know him twofold through the twofold experience of your senses. Thus you will see with your eyes what you have learned through the words you have heard. He who in this way hears and sees will fill his entire being with the praise of God.” [quoted by Cardinal Schonborn, p232, God’s Human Face, pub. Ignatius.]

It is good, therefore for us to develop the habit of praying with visual imagery and this can start at home. The tradition is to have a corner in which images are placed. This image or icon corner is the place to which we turn, when we pray. When this is done at home it will help bind the family in common prayer.

![]() Accordingly, the Catechism of the Catholic Church recommends that we consider appropriate places for personal prayer: ‘For personal prayer this can be a prayer corner with the sacred scriptures and icons, in order to be there, in secret, before our Father. In a Christian family kind of little oratory fosters prayer in common.’(CCC, 2691)

Accordingly, the Catechism of the Catholic Church recommends that we consider appropriate places for personal prayer: ‘For personal prayer this can be a prayer corner with the sacred scriptures and icons, in order to be there, in secret, before our Father. In a Christian family kind of little oratory fosters prayer in common.’(CCC, 2691)

I would go further and suggest that if the father leads the prayer, acting as head of the domestic church, as Christ is head of the Church, which is His mystical body, it will help to re-establish a true sense of fatherhood and masculinity. It might also, I suggest, encourage also vocations to the priesthood.

The placement should be so that the person praying is facing east. The sun rises in the east. Our praying towards the east symbolizes our expectation of the coming of the Son, symbolized by the rising sun. This is why churches are traditionally ‘oriented’ towards the orient, the east. To reinforce this symbolism, it is appropriate to light candles at times of prayer. The tradition is to mark this direction with a cross. It is important that the cross is not empty, but that Christ is on it. in the corner there should be representation of both the suffering Christ and Christ in glory.

‘At the core of the icon corner are the images of the Christ suffering on the cross, Christ in glory and the Mother of God. An excellent example of an image of Christ in glory which is in the Western tradition and appropriate to the family is the Sacred Heart (the one from Thomas More College's chapel, in New Hampshire, is shown). From this core imagery, there can be additions that change to reflect the seasons and feast days. This way it becomes a timepiece that reflects the cycles of sacred time. The “instruments” of daily prayer should be available: the Sacred Scriptures, the Psalter, or other prayer books that one might need, a rosary for example.

This harmony of prayer, love and beauty is bound up in the family. And the link between family (the basic building block upon which our society is built) and the culture is similarly profound. Just as beautiful sacred art nourishes the prayer that binds families together in love, to each other and to God; so the families that pray well will naturally seek or even create art (and by extension all aspects of the culture) that is in accord with that prayer. The family is the basis of culture.

Confucius said: ‘If there is harmony in the heart, there will be harmony in the family. If there is harmony in the family, there will be harmony in the nation. If there is harmony in the nation, there will be harmony in the world.’ What Confucius did not know is that the basis of that harmony is prayer modelled on Christ, who is perfect beauty and perfect love. That prayer is the liturgical prayer of the Church.

A 19th century painting of a Russian icon corner

Creativity and Fun with Substance

Dudley Moore parodying Beethoven piano sonato and Schuber lieder ('Die Flabberghast') I saw the first video below on Damien Thompson's blog on The Daily Telegraph website. It is Dudley Moore playing his own composition, a parody of a Beethoven piano sonato based on the melody of Colonel Bogey (or if you prefer the tune from the Bridge Over the River Kwai). It is recorded in the Sixties. I have spoken about how important creativity within a tradition is for keeping it alive and opening the door that leads to the timeless principles that are at its core for modern audiences. In the context of sacred music, I described this a need for composers whose work has the quality of noble accessibility, see here.

This is not sacred music, but it is just the sort of creativity that will open the door to the real thing, drawing people in through more than just he music. I find it brilliantly funny.

Moore was organ scholar at Magdalen College, Oxford. After university he achieved national prominence as jazz pianist and then as part of the Beyond the Fringe comedy quartet with Alan Bennet, Jonathan Miller and Peter Cook. Jonathan Miller, who went on to become a famous opera director (among other things) is the figure opening the piano lid for him before he performs. Alan Bennet and Peter Cook especially also became household names in Britain. Bennet is a playwright and Cook a comedian with whom Moore eventually formed a famous duo.

All were at Oxford University. This creativity is encouraged by the form of education that exists at Oxford and in form (if not so much in substance any more) is based upon the medieval university. I am always amazed that more educational institutions do not copy this given the success of the two universities, Oxford and Cambridge, that bear the mark of the medieval university today. All those in continental Europe were destroyed by Napoleon and re founded on a different organisational model. American universities and colleges, even the Catholic ones, are almost all based upon this later, German model. I have written about this here.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GazlqD4mLvw

Here is another video, this time Moore's parody of a Schubert Lieder 'Die Flabberghast'

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=idBZPteNJxs&feature=related

Wild Flowers in Spain (and Possible Implications for Population Control and the Culture of Death)

During my visit to friends and family in Europe, I spent a a few days in Spain (during the last week of May). My parents have retired there (along with another million Brits). I was lucky in that the time of my visit was just the time when wild flowers are in bloom. I am no plant expert, but I did recognise a lot from my memories of my parents' garden in England when I was growing up. So I asked them if they would help me identify some of the plants and we set off to high meadows to photograph and identify them.

Also, I am trying to plant an English style perrenial garden in the farm that will be the new Thomas More College campus in Groton, Massachusetts. (I say 'will be' because we have to raise the money to build. This is not easy in the current economic climate, so please if anyone feels like donating, don't hesitate to contact us!) We have been following the planting scheme of the English garden designer Gertrude Jeckyll. From my first spring of planting here in the US, I recognised that many of the Spanish plants are in American gardens too. The photo above is of a thistle called echinops. We bought three to plant and they look pretty lonely at the moment while we wait for them to flourish and multiply. Here in Spain, there is a whole field of them next to my parents' house just growing wild.

During my visit to friends and family in Europe, I spent a a few days in Spain (during the last week of May). My parents have retired there (along with another million Brits). I was lucky in that the time of my visit was just the time when wild flowers are in bloom. I am no plant expert, but I did recognise a lot from my memories of my parents' garden in England when I was growing up. So I asked them if they would help me identify some of the plants and we set off to high meadows to photograph and identify them.

Also, I am trying to plant an English style perrenial garden in the farm that will be the new Thomas More College campus in Groton, Massachusetts. (I say 'will be' because we have to raise the money to build. This is not easy in the current economic climate, so please if anyone feels like donating, don't hesitate to contact us!) We have been following the planting scheme of the English garden designer Gertrude Jeckyll. From my first spring of planting here in the US, I recognised that many of the Spanish plants are in American gardens too. The photo above is of a thistle called echinops. We bought three to plant and they look pretty lonely at the moment while we wait for them to flourish and multiply. Here in Spain, there is a whole field of them next to my parents' house just growing wild.

The terrain in this area around Spain is man made. Even the areas where the flowers grow and seem uncultivated would be completely tree covered if they had not been cleared by man. It is dry, shrub filled landscape common in Mediterranean areas called 'maquis'. Very often the flowers flourish most on road or field edges in the areas where the soil has been turned over by human activity but it has not been paved over or planted with crops. A common plant in the maquis terrain is the broom. There are two common varieties here: Spanish broom and genista (French broom) which has smaller flowers, both are bright yellow. The photo below shows some genista growing on the edge of a cultivated olive grove. In the distance you see a ridge of mountains with pass, appearing as a notch cut into it. For our flower hunting expedition we headed for that pass. There is a footpath there on a disused railway line which allowed for great views and a great variety of species.

The fact that the whole terrain is formed by man raises a question in my mind. What is the natural environment for wild flowers? Would these flowers be here at all if it weren't for man? If there were no man affected areas, would there be any terrain for them to grow in? Certainly, the ones I saw don't grow in the areas that are wooded, only on the edges made by man. Perhaps there are some plant experts out there who can answer these points definitively. What I can say is that these flowers are flourishing in those areas affected by man. If this man-affected terrain is the natural environment for wild flowers, and wild flowers are considered part of the natural world (along with the insect life engendered), then we would have to consider man's activity natural too.

The fact that the whole terrain is formed by man raises a question in my mind. What is the natural environment for wild flowers? Would these flowers be here at all if it weren't for man? If there were no man affected areas, would there be any terrain for them to grow in? Certainly, the ones I saw don't grow in the areas that are wooded, only on the edges made by man. Perhaps there are some plant experts out there who can answer these points definitively. What I can say is that these flowers are flourishing in those areas affected by man. If this man-affected terrain is the natural environment for wild flowers, and wild flowers are considered part of the natural world (along with the insect life engendered), then we would have to consider man's activity natural too.

Some extreme environmentalists that I have come across tend to assume that man's activity is unnatural and always detrimental to the ecosystem. I'm guessing that there others who object to the activities of modern man, but would consider a pre-industrial revolution, agrarian society (which would still create the landscape for wild flowers) as the natural form of activity for man. The first group would like to see man's effect on the world eliminated altogether, the second vastly reduced.

The reason that this is important to consider is that the degree to which we consider mankind's activity natural or unnatural affects whether or not we consider the the growing human population of the world a good thing or a bad thing. In both the cases cited above, that is if either we consider man's activity necessarily unnatural; or, taking the less extreme position, we consider the work of modern man unnatural and only that of primitive man's activity natural, it makes sense to advocate population reduction in the world. The few examples of modern man there are, the less unnatural behaviour there will be. The next step is to push for population control via the use of contraception and abortion.

The traditional Christian view is different. For the Christian man is the crowning glory of creation and his activity is not only natural but, potentially, the greatest of all life on earth. In fact, to the degree that his work is inspired, man can actually raise the natural world up to something higher, creating something closer to what it ought to be and to what it would have been prior to the Fall. This is not deny that man's activity can be highly destructive also. It depends on how wisely he makes use of his God-given freedom to cultivate the land.

When we have the Christian outlook, the way to deal with polution and mismanagement of the environment, is not to reduce the amount of human activity (by reducing the population), but to seek to transform human activity into something that is in harmony with creation. This is possible (at least partially in this life) only through the Church and this takes us again to the question of cultural transformation and liturical reform. Two connected themes I have spoken about often in this forum.

Anyway, we have now reached the high meadow and start to walk along the path through the notch:

We surveyed the scene, book in hand:

We surveyed the scene, book in hand:

And then we started to look more closely. You can see the red poppies and yellow daisies in the meadow. But as you look at the limestone rock outcrops there are more to be seen, for example wild tyme:

Orchids and wild irises:

Here is another iris amongst a cluster of flowers of helianthemum, the rock rose, a common plant in the the garden.

In our day out, we did take time step back and enjoy the view of rural Spain from this elevated position.

Where irrigated, the ground is extremely fertile. This part of Andalusia exports fruit and vegetables. The view below is of the area beyond that notch in the ridge. There is a high fertile plain hidden away. The old railway track that we were walking on was built to carry the produce down to the coastline (near Malaga) for distribution. Now the transportation is by road you see trucks driving down the winding road all day during harvest time.

The examples of the flowers shown are as bright and beautiful as the garden varieties. There were many more that I could show, and will perhaps keep for another occasion. Many of these while beautiful in the wild, are not precisely what you would see in the garden, which would be hybrids. This again raises the question of what is more natural, a hybrid developed by man or a wild variety? Anyway, that's one for a future blog post.

How Do We Develop the Cultural Sensibilities of Children?

I am regularly asked by parents how they can teach an appreciation of good traditional art to their children. One father recently went further than that and asked me if there was anything I could do to unculturate them in such a way that their sensibilities are in tune with a catholic culture in its broadest sense. These are the ideas that I offered to him.

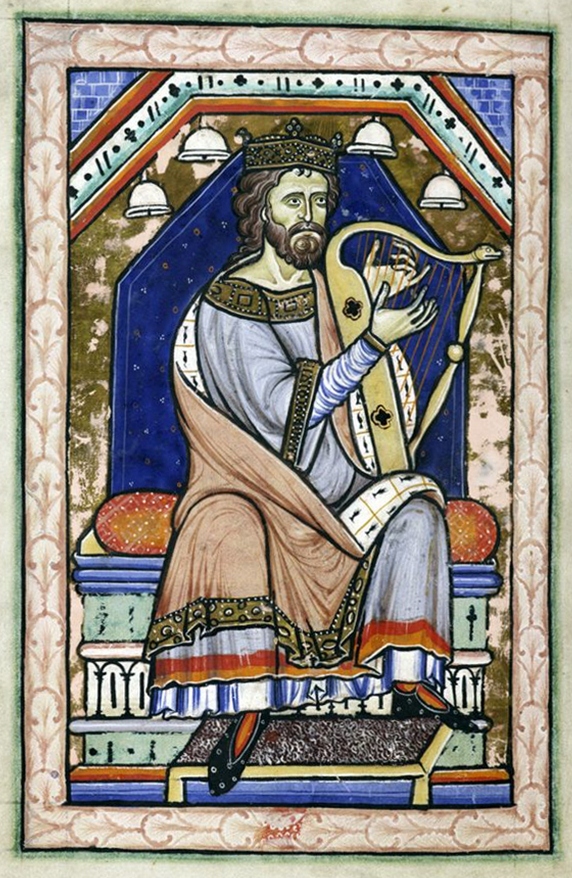

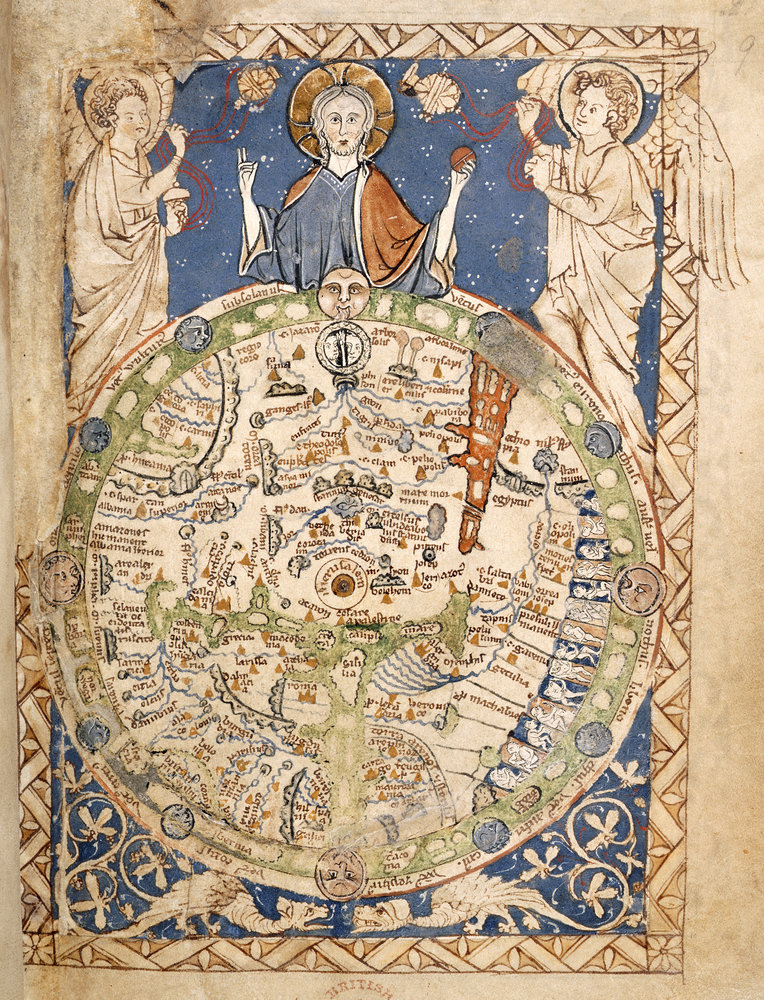

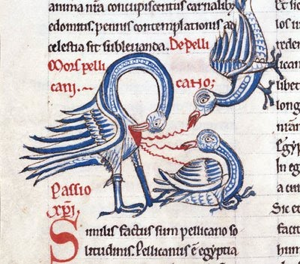

1. All traditional training in art involves drawing by copying from nature and then copying the works of Old Masters. Ideally children would do both but precisely what they try to draw depends on how old they are. Very young children could colour in line drawings based upon traditional forms - I illustrated a couple of books with this in mind, for example see Sacred Heart of Jesus Coloring Book. The more sophisticated might be able to try some tonal work on a copy of a baroque painting. A great start for anybody would be gothic or Romanesque illuminated manuscripts. These are line drawings with limited modelling. They are great fun to draw and my experience is that Catholics relate to these Western icons more readily than to Eastern iconographic forms. If you to get hold of examples type 'psalter' into the Google Images search engine. You don't need to feel bound to sacred imagery. The psalters of this period contained pictures of the everyday life at the time. All the examples shown here are from the Westminster Psalter.

I am regularly asked by parents how they can teach an appreciation of good traditional art to their children. One father recently went further than that and asked me if there was anything I could do to unculturate them in such a way that their sensibilities are in tune with a catholic culture in its broadest sense. These are the ideas that I offered to him.

1. All traditional training in art involves drawing by copying from nature and then copying the works of Old Masters. Ideally children would do both but precisely what they try to draw depends on how old they are. Very young children could colour in line drawings based upon traditional forms - I illustrated a couple of books with this in mind, for example see Sacred Heart of Jesus Coloring Book. The more sophisticated might be able to try some tonal work on a copy of a baroque painting. A great start for anybody would be gothic or Romanesque illuminated manuscripts. These are line drawings with limited modelling. They are great fun to draw and my experience is that Catholics relate to these Western icons more readily than to Eastern iconographic forms. If you to get hold of examples type 'psalter' into the Google Images search engine. You don't need to feel bound to sacred imagery. The psalters of this period contained pictures of the everyday life at the time. All the examples shown here are from the Westminster Psalter.

Drawing from nature, even for the most simple subject is more difficult. When the child is prepared to give it a go start with simple but interesting forms that don't require the child to summarise. So drawing a tree is very difficult, because it presents the problem of how to deal with thousands of leaves, but drawing a single daffodil is a bit easier; and a smooth ball or a cup easier still.

2. Pray the Liturgy of the Hours in the family. This is perhaps the single most important item. Where possible the father, as head of the family, should lead the prayer and it should be sung. Wherever possible the psalms should be sung and the prayer should be oriented towards sacred image or images. Interestingly, I made some suggestions to this person who asked my about how he might sing compline with his children. I sang some very simple tones which he recorded on his laptop so that he could learn them (they were from the selection I developed myself with instructional videos, here). Then I showed him how to point any psalm so that any of these tones could be applied to them. He told me later that his children loved to sing the psalms and were competing for turns to sing on their own.

2. Pray the Liturgy of the Hours in the family. This is perhaps the single most important item. Where possible the father, as head of the family, should lead the prayer and it should be sung. Wherever possible the psalms should be sung and the prayer should be oriented towards sacred image or images. Interestingly, I made some suggestions to this person who asked my about how he might sing compline with his children. I sang some very simple tones which he recorded on his laptop so that he could learn them (they were from the selection I developed myself with instructional videos, here). Then I showed him how to point any psalm so that any of these tones could be applied to them. He told me later that his children loved to sing the psalms and were competing for turns to sing on their own.

3. As soon as possible learn to chant. Even if it is the simplest form of chant, and introduction to the eight modes will benefit the child more than conventional music, I believe. The intervals and harmonious relationship that are traced out in music impress upon the soul the essential patterns that comprise the beauty of the cosmos and which ultimately point, to use the phrase of Cardinal Ratzinger in the Spirit of the Liturgy, to the 'mind of the Creator'. Conventional music contains only two of the modes and so if the child is only exposed to the major and minor keys, no matter how beautiful the music, they will have a limited educational benefit.

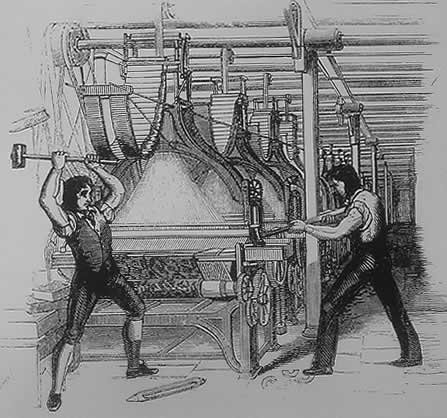

What is Culture?

When I teach my class at Thomas More College I use a definition I heard in a talk from Fr Rob Johannson of the Diocese of Kalimazoo in Michigan about the Evangelisation of the Culture. He described it as that activity of man that reflects and in turn nurtures the core beliefs, values and priorities of the society. It is derived from the Latin word for field because traditionally it was always seen as something that has to be nurtured in order to preserve those core values, and hence preserve the society.

When we ponder on this, we can see that all activity of man constitutes the culture. It is not just high art, it is the most mundane activities - how we pick up a knife and fork when eating, how do we design our road signs...even how do we drive. And here's another critical point: given that free will is involved, how we do these things can potentially be destructive to society, as well as constructive. I have never held the view, for example, that we must return to an agrarian society. Industrialisation, as high-tech as you like, can be a beautiful thing if it is the product of a truly Christian society. The reason that we tend to assume that it is intrinsically desctructive is that the industrialisation of the West has taken place in post Enlightenment society and so reflects that worldview - the result is ugliness and suffering. But it need not be so. The goal, I believe, is to transform what we have for the better, not to wipe the slate clean an try to go back in time. It is interesting to note, that modern agriculture bears the characteristics of factory more than the idyllic agrarian scene that we associate with the ancient and carefully preserved farmland of Europe that was given it's characteristic look long before the modern age.

When I teach my class at Thomas More College I use a definition I heard in a talk from Fr Rob Johannson of the Diocese of Kalimazoo in Michigan about the Evangelisation of the Culture. He described it as that activity of man that reflects and in turn nurtures the core beliefs, values and priorities of the society. It is derived from the Latin word for field because traditionally it was always seen as something that has to be nurtured in order to preserve those core values, and hence preserve the society.

When we ponder on this, we can see that all activity of man constitutes the culture. It is not just high art, it is the most mundane activities - how we pick up a knife and fork when eating, how do we design our road signs...even how do we drive. And here's another critical point: given that free will is involved, how we do these things can potentially be destructive to society, as well as constructive. I have never held the view, for example, that we must return to an agrarian society. Industrialisation, as high-tech as you like, can be a beautiful thing if it is the product of a truly Christian society. The reason that we tend to assume that it is intrinsically desctructive is that the industrialisation of the West has taken place in post Enlightenment society and so reflects that worldview - the result is ugliness and suffering. But it need not be so. The goal, I believe, is to transform what we have for the better, not to wipe the slate clean an try to go back in time. It is interesting to note, that modern agriculture bears the characteristics of factory more than the idyllic agrarian scene that we associate with the ancient and carefully preserved farmland of Europe that was given it's characteristic look long before the modern age.

Here is a passage that I read in the Office of Readings on May 1st, the Feast of St Joseph the Worker. It is from the pastoral constitution on the Church in the modern world of the Second Vatican Council and has the subtitle 'The worldwide activity of man'. This describes the idea of all activities of man giving glory to God, just as the cosmos - the rest of His creation - does through its beauty and grace. Furthermore, that the cosmos is made better by this activity. It stresses the need for a connection between the faith and the wider culture. This goes back to liturgical reform, so that our participation in the liturgy, which I feel must include the liturgy of the hours, engages the whole person and then the Divine Beauty is impressed upon our souls and inclines us to order all our activities to it.

Here is a passage that I read in the Office of Readings on May 1st, the Feast of St Joseph the Worker. It is from the pastoral constitution on the Church in the modern world of the Second Vatican Council and has the subtitle 'The worldwide activity of man'. This describes the idea of all activities of man giving glory to God, just as the cosmos - the rest of His creation - does through its beauty and grace. Furthermore, that the cosmos is made better by this activity. It stresses the need for a connection between the faith and the wider culture. This goes back to liturgical reform, so that our participation in the liturgy, which I feel must include the liturgy of the hours, engages the whole person and then the Divine Beauty is impressed upon our souls and inclines us to order all our activities to it.

Here is the passage:

"Man, created in God’s image, has been commissioned to master the earth and all it contains, and so rule the world in justice and holiness. He is to acknowledge God as the creator of all, and to see himself and the whole universe in relation to God, in order that all things may be subject to man, and God’s name be an object of wonder and praise over all the earth.

The Psalms and the Evangelisation of the Culture

I recently read The Liturgical Altar by Geoffrey Webb. Originally written in 1936 and republished just last year, this has been referred to a number of times by New Liturgical Movement writers. I was reading it, as one might expect, to try to find out more about the design of altars, but a short section at the end where he discusses general principles caught my eye.

I recently read The Liturgical Altar by Geoffrey Webb. Originally written in 1936 and republished just last year, this has been referred to a number of times by New Liturgical Movement writers. I was reading it, as one might expect, to try to find out more about the design of altars, but a short section at the end where he discusses general principles caught my eye.He wrote: ‘Anyone familiar with what remains of the forms of liturgical art in England before the break in religion in the sixteenth century must be impressed with one characteristic feature in it. Its beauty appears to share with the wild flowers, and with all the natural order, that absence of toil and effort to which Our Lord Himself drew attention in the lilies of the field. Beauty is an essential attribute of God; and some visible reflection of it would seem to be an inevitable accompaniment of any true worship of God, whenever the spirit of the Liturgy is allowed to give a form to the arts. At certain periods in the Church’s history this visible beauty overflows into all the arts of everyday life. This is the case when the Church can so permeate a whole civilization that she is free to distribute other benefits over and above the one essential blessing of Faith. At such times, education, in the sense of formation of good taste and sound judgment, becomes the common property of the whole community; and the common things of daily use seem to share in the unself-conscious beauty of nature…Beauty, unless ruled by the Cross, generates the seeds of its own destruction.’