The iconographic stylization persisted in Italy in some regions due in part to the fact the some parts of Italy remained under Byzantine rule until as late as the 11th century and the painting style continued, passed down by tradition.

From the Iconographic to the Gothic

The History of the Icon of the Transfiguration

Hold the Line! The Iconography and Workshops of George Kordis

George Kordis is offering classes in Athens and Crete this summer in English, see writingthelight.com. For those who don't have the resources and time to get to Greece, Kordis is now offering online courses at iconographytoday.com/en.

Hermits, Icons, and the Sacred

God First

Can You Paint a Holy Icon of Someone Not Yet Canonized? The Answer is Yes!

The painting of the image is part of the natural process of growing devotion that always occurs prior to canonization. This is the process by which we collectively and organically recognize the sanctity of someone. The official canonization comes after this and does not make someone a saint, it merely accepts what is already known.

Illuminations from the Macedonian Renaissance of the 9th Century

Here are some folios from the Paris Psalter. An anonymous reader brought these to my attention because he thought I might be interested in the similarity in style to the 6th-century Mesopotamian illumination I featured last week.

The Paris Psalter is not French! It was procured by the French ambassador to Constantinople around 1550. The city was in the hands of the Ottomans at this time. They date from a period of Greek art known as the Macedonian Renaissance in which there is a flourishing of a more naturalistic style of iconography which clearly draws on antique classical style. It is this style of iconography that inspired the Romanesque style in the West which is, as with these, an authentic iconographic tradition.

Many modern iconographers look to this period for inspiration, because it is felt that the naturalism would appeal the modern eye. The highly abstracted Russian style of the 15th century, for example, though well known can be too abstracted for some, it is felt.

Here, for example, is David composing the psalms.

David Composing the Psalms

David and Goliath

These are large - approximately 14' x 10'. Things that struck me about these, are that there is some naturalistic perspective here, even down to color perspective - see how the distant objects are blue. In this sense, they are reminiscent of the style of frescoes of 1st century Pompeii that I have seen.

Nevertheless, the handling of the perspective is still enough off-natural to be iconographic, it seems to me. The relative sizes of the figures do not change from foreground to distance, for example. I would love to know how Eastern Christians view these images. Do you consider these authentically iconographic or do you feel they push the envelope too far into naturalism?

Notice also how Roman the clothing looks also and the beautiful and intricate border patterns.

David Glorified by the Women of Isreal

The Healing of Hezekias

Isaias's Prayer

The Reproach of Nathan and the Penance of King David

Hannah's Prayer

Saint Lazarus the Painter, and the Artist in Heaven

Saint Lazarus Zographos (the painter) believed that we do not live for the here and now, we live for the future. We are not content with what is, but struggle to achieve what should be and what will be. As pilgrims on this earth we look to the future. The earth is not heaven, it is the path to heaven.

Contemporary Icons from Poland

Devotion, Design and Decoration - How Liturgical Art Influences the Wider Culture

We need art that is clearly derived from the liturgical forms but is distinct from it and directs us to purest form, so to speak, by being part of the wider culture of faith. This is the beginning of the process by which the liturgy, which is a source of its own culture, begins to push out into the wider culture and transform it into a Christian culture.

Wearing Your Heart on Your Lapel - A Novel Way to Bear Witness to Christ

I recently did a FB photopost on my icon lapel pin, and was surprised by the positive reaction, so I decided to write a little bit more about it!

In the West, we live in a time of steadily increasing hostility towards Christianity. Famously, the late and much missed Cardinal George of the Archdiocese of Chicago, who died of cancer in 2015, summed up the situation with the following statement made several years before his death:

I expect to die in my bed, my successor will die in prison and his successor will die a martyr in the public square.

This statement caught attention at the time, but it is not quite as pessimistic a statement as some have suggested. Clearly, there is an assumption here that his successors would be as orthodox in their faith as he was in his, and so merit attack from secular forces. Some might say that in itself was optimistic to the point of foolishness! But also, he went on to say in the same statement, that after the death of the martyr bishop:

His [the martyr's] successor will pick up the shards of a ruined society and slowly help rebuild civilization, as the church has done so often in human history.

In other words, we should not lose heart, for the Church will prevail regardless of the malice of men or the devil.

I thought about this recently when I heard a homily about the need to bear witness to the Faith today. The pastor made the point that while we are not at the point yet of being persecuted for our faith in this country, it might happen in the future and it is more likely to happen if we do not stand up for the Faith now. Countering prejudice at an early stage, he suggested, can help to stop it growing into open hatred and persecution in the future. He reminded us of how blessed we are in this country, still, compared with many who live in real fear for their lives for practising their faith, especially those in some predominantly Islamic countries.

I pray that if required, I might have the courage of the martyrs through the centuries who stood up to oppression whether it be from ISIS or the Emporer Diocletian.

In the meantime, the question is what can I do here and now to play my part? How do I bear witness in such as way that people know that I am Catholic and is likely to create a positive enough impression to draw people to the Faith?

The first thing, I think, is to acknowledge my need for God's grace to be able even to begin to live up to Christian ideals.

Second is let people know that I am a Christian. I live in the San Francisco Bay area and I often hear derogatory remarks about Christians and Christianity. Wherever possible I try to respond by casually and cheerily remarking that I am Christian. Usually, that has the simple effect of halting the conversation because no longer is 'the Christian' an abstraction in their imaginations, he is a real person. And I find that even here, most people shy away from offending flesh-and-blood people standing in front of them.

In his sermon, our pastor (at St Elias Melkite Catholic Church) suggested one simple way of discreetly but visibly making such a statement would be to wear a cross. He said that it would arouse curiosity and people would ask what it was. It would also, he suggested, give us the motivation to be better Christians because we are so clearly identifying ourselves with the Faith.

I have bought one and wear it, but I'll admit it sits under my shirt, only sometimes visible when I have an open-necked shirt. A necklace or medallion is not something that I would ordinarily wear and I don't feel absolutely comfortable with it. I decided to do something different that felt more natural to me. I found a company online that makes personalized lapel pins and so asked them to create some for me based on the Holy Face. I sent them a jpeg of the following icon:

When the batch came (I had to order 100) they looked like this:

Already, people have asked about it, and one even asked where I go to church, so I gave her a St Elias Melkite Catholic Church business card (which the pastor had printed up and encouraged us to have in our wallets, just in case!). I also see many people looking at it when I wear it although most do not say anything. Nevertheless, I am pleased about this because I feel that I have made a statement without saying anything in a way that I feel comfortable with.

I might be wrong, but I don't feel I am the sort whose natural gifts extend to being able to attract people to the Faith by standing on a soapbox and preaching on a street corner to passers-by; or by wearing a sandwich board that says: 'The End is Nigh' - as a man used to do for years in Liverpool city center when I was growing up in the 1960s and 70s.

Perhaps I am less courageous than this man. But a lapel pin is my way of being in-your-face with the Holy Face, while not looking as though that's what I'm trying to do. It was easy enough to do - you could easily create your own if you have a jpeg file of an image you like.

I am curious to hear from readers. Do you have any ways that tell people you are Christian without putting people off? I'd love to hear about what you do and the reactions you get. This is probably something that would appeal more to men than women, so what might women do alternatively?

Meanwhile, I am still waiting for someone to come up and incense my jacket...perhaps one day, you never know.

Radiant Truth - How the Thomism of Fr Norris Clarke Explains The Style of Holy Icons

'For with You is the fountain of life, and in Your Light, we shall see light.'

Many readers of this blog will be familiar, I'm sure, with the idea that there is a theology that is used to explain the stylistic elements of the iconographic liturgical art. However, I am not aware of a metaphysics or philosophical anthropology that has been or could be used to articulate a philosophy of icons.

That is, until recently.

A couple of years ago, on the recommendation of a Dominican friar here in Berkeley, I read two works of the late Jesuit philosopher, Fr Norris Clarke. These were Person and Being, and The One and the Many - A Contemporary Thomistic Metaphysics. You can see an interview with him shortly before his death in 2008, here, on YouTube in which he talks about his 'personalist' Thomism.

More recently, I sat in on a series of excellent lectures on the thought of Fr Clarke as part of a class on the philosophy of nature and philosophical anthropology, taught by Dr. Michel Accad for Pontifex University's Master of Sacred Arts program. Dr. Accad had invited me to attend so that I might participate by discussing with him why an understanding of philosophy is important for artists today.

There are, incidentally, a number of general reasons why such a class would be included in a sacred arts program - for example, the simple fact that an understanding of the human person and nature is always important for an artist who is seeking to reveal both invisible and visible truths about both through art. However, it occurred to me as I listened and reflected on the subject that Fr Clarke's Thomistic philosophy, in particular, might be the basis for a philosophy of icons. I offer my thoughts on this as some personal speculation for your interest.

We will start with a brief account of some of the ways in which theology has been used to explain the style of icons.

Take a look at this icon of the Transfiguration,

...we see Christ shining with light. This is understood to be a glimpse given to the Apostles of his heavenly glory. That glory, which is the radiance of his being, is the radiating of an uncreated 'light of being', the divine light of the burning bush, that shone without consuming the bush itself. Saints, who through baptism and lives of purity participate in the divine nature shine with this light too; and in their purity are able to see in ways that we can only grasp 'through a glass darkly'. This radiance is represented by the halo of light around their heads. Another indication that each figure is a source of light is indicated by the fact that none have cast shadows.

Even the apostles, who are not shown with halos (indicating that this event is prior to Pentecost when the fire of the Holy Spirit came to them) are nevertheless shown without cast shadows. This reflects the fact that in some way and at this moment, they must have been at least temporarily purified. For only the 'pure in heart' who are themselves participating in the divine nature can see the divine light. Even so, the power of such a vision to those who are unused to seeing it has knocked them back as we can see!

There are other stylistic elements that reflect truths about the objects portrayed that are not ordinarily visible. So there is a hierarchy of being in which Christ is greatest, mankind is next and inanimate beings come next. This is reflected visually by having Christ the most prominent figure amongst the six, through the design - and his size and brightness and the way in which his image relates to the other people in the composition. The mountain, on the other hand, is small relative to its natural size. In some icons, plants and mountains will be depicted actually bowing to Christ to communicate this point.

While the discussion so far relates to visible light, which is the only way that an artist working in a visual medium can portray such radiance, the light he is portraying is not in fact limited to visual light or even to electromagnetic radiation. This radiance is of a divine, uncreated supernatural 'light' that is visible to the purified 'spiritual eye', the place inside us where we see, so to speak, truth, and are connected to God. This is the 'spirit' of the Pauline anthropology (body, soul, spirit), which Stratford Caldecott, for example, equated with the intellectus of the Western medievals, and the nous of the Eastern Fathers, see here.

So how can philosophy account for this? First, it is worth describing the work of Fr Norris Clarke who is a philosopher in the true sense. He develops his own original thought, still working in the Thomistic tradition. Dr. Accad was kind enough to give me a summary of the salient points.

He wrote:

'I agree, that the work of Fr. Norris Clarke (which we cover at the end of the course, as a kind of summary and integration of everything we have learned) is likely to provide a helpful framework. Here are some of the points that Fr. Clarke distills from St. Thomas’ metaphysics (and to which he adds insights from modern “personalist” philosophy):

'The universe is an immense family of real beings, and all real beings—from the simplest drop of water to the human person—have something in common: They all exist! In technical terms, all real beings share in the act of existence. What’s more, we are all intimately connected with the source of our existence, God, who is existent in Himself (“I am who am”)

'Although all created beings share in the act of existence, each being is limited by an essence: A dog is a share of existence possessed—and limited by—the essence of “dogginess” and an oak tree is a share of existence possessed and limited by the essence of “oakiness”. God, of course, is unlimited, infinite being. According to St. Thomas, His essence is existence.

'Because created being are all finite and limited by essence, we each have something to receive from the rest of the family of beings, but we each also have something to contribute to other beings. All beings are constantly communicating of themselves to others and receiving from others to complete and perfect themselves.

'For example, even a simple pebble communicates its own existence to the rest of the world. Modern science acknowledges that: For one thing, by its existence, the pebble contributes materially to the gravitational field of the planet—even if in a most modest way. Without that gravitational field, we would all be floating about in the ether, getting evermore separated from one another!

'Because to be real is to be giving and to be receiving, we are all substances in relation. This is particularly true in the higher beings, like animals and humans who are constantly giving and receiving from one another, but it is even true at the lowest level. Water, for example, is molecular beings that are in relation with one another. Each molecule of H2O gives of itself to its neighbor and receives the actions of its neighboring molecules. The consequence this mutual interaction is a community of molecular beings that has the property of being clear, liquid, and life-sustaining for all living organisms!

'Clarke’s rendition of Thomistic metaphysics describes a wonderful community of beings, each of which, in its own way, reflects, refracts, and radiates the light of the Creator to all other beings.'

Man, of course, occupies a special place in the universe. Being at once a spirit united to a material body, he is an “amphibian” straddling the world of angels and that of earthly creatures. Because he possesses and intellectual nature that allows him to form civilizations, he leads creation on its journey back to the Creator. And, as spirit, man is also person: individually distinct and self-possessing and capable of living in self-conscious and self-determining community with others, in the image of the community of Divine Persons.

I do not know if Fr Clarke himself ever connected his ideas to the theology of the icon, but the parallels seem clear. He is describing this radiance of being in ways that are compatible with the uncreated light of being referred to by the theologians of the past, and which is manifested visually in the icon.

As I read Fr Clarke's books, this picture of being as an activity, a static dynamism in which each is giving and receiving of itself superabundantly (that is without depletion) reminds me of the dynamic of love described by Benedict XVI is his encyclicals. Benedict talks of love as simultaneous actions of self-gift and ordered reception of persons in relation, terming them agape, and eros respectively. I have written about this here.

Also, Clarke's philosophy helps me to understand something about the nature of beauty itself, which is sometimes defined as the 'radiance of being'. Beauty is an objective quality, that is, it is as an aspect of the thing considered beautiful; and in the full perception of its existence we, the subjects observing it, delight in it. But beauty has, nevertheless, a subjective component, for different subjects will have differing abilities to 'see', that is to apprehend, the incident 'light' of being emanating from the object.

I finish with an affirmation from the greatest school of theology and of life and all, that is, the liturgy. Light and life are connected in the hymn in the Eastern Rite called the Great Doxology. It opens with the proclamation, 'Glory to You, O Giver of light!' This is the divine light which we all participate in through our existence, which as human beings incorporates life, and which we possess in the fullness of our capabilities by partaking of the divine nature as baptized Christians. The connection is made explicitly later in this same hymn with the words: 'For with You is the fountain of life, and in Your Light, we shall see light.'

The fountain of life!

What is this if not the self-effusive activity of being made all the more resplendent with the supernatural gift of life by which we relate to each other and with God in love in, at its consummation, the liturgy?

As an aside: in the Mandylion above, which I painted, I was told that the rounded brow that sits in the V between the eyebrows can be thought of as the 'spirit' or the 'spiritual eye' of the person that 'sees Light'.

Pontifex University is an online university offering a Master’s Degree in Sacred Arts. For more information visit the website at www.pontifex.university

Florentine Street Shrines - Can We Do This Today? Will Today's Della Robbia Please Step Forward?

When I was studying portrait painting in Florence, several years ago, I was struck by the charm of the old street shrines that can be seen built into the walls of the buildings that line the narrow streets. Many date back to the time of the building itself.

Not all are still obviously the focus for prayer, many seemed to unnoticed in a city in which Renaissance art abounds and much of the population has fallen away from the Faith.

Since then I have wondered, from time to time, if this is something we could do today, in a time and in places where Catholicism is not the dominant faith and the driving force the culture?

My feeling is we might, in many instances, struggle to persuade local government to go along with such a thing. However, perhaps if done tastefully and discretely on private property that is visible from the public street it might be possible.

I suggest that if what is done is truly beautiful, even non-believers would want it and it would, to a large degree, disarm potential critics by removing their desire to be offended by outward signs of the Faith. I have a friend who runs a menswear shop in the UK and he always places a small icon of the face of Christ, a Mandylion, which is just 6' x 4' in size, low down on the wall behind the counter. While it is not an obviously bold statement of faith, he deliberately places in such a position that when people pay for their clothes, they will see it on the wall behind the till in such a way that it gives the impression that they are peeking into his personal space and seeing an image that is their for his private devotion. He says that nobody ever objected, and many asked about it.

Non-Christians (and for that matter many Christians too) are much more likely to be irritated if the art is ugly or sentimental. I have often wondered, for example, if the militant secularists are in fact doing us a favor by objecting to the kitsch shopping mall nativity scenes that seem to be standard issue for retailers nowadays. Perhaps they are the unwitting agents of the Holy Spirit? Before my conversion in my early thirties, piped carol music and brightly-colored plastic McChristmasses gave me the impression that Christianity was for saddoes who didn't even know that they ought to be embarrassed by being associated with this stuff. This did far more to put me off the Church than tales of Popes fathering illegitimate children or the brutality of the Teutonic Knights in the Baltic and the Middle East!

If we did decide to do this, what form should it take?

Well, here's an idea. I recently posted a photo of my first stab at creating an outdoor icon corner in a balcony garden.

I am hoping that as the plants grow through spring and summer that the hard edges will soften and overgrow, slightly the images. The paintings are prints that I obtained from a website selling them on rustic wooden planks, which I have varnished and screwed to the stool, which came from a consignment store.

A reader saw the photos and got in touch with me, suggesting that someone might like to start producing ceramic tiles with the standard core images of the icon corner - Our Lady on the left, the crucifixion in the center and the Risen Christ on the right which could then be set into the wall.

I do not know the economics of tile production but wouldn't it be wonderful if we could have beautiful triple sets of tiles? I imagine they might be something like the Della Robbia ceramics, except stylistically gothic or iconographic (just to suit my personal taste) and polychrome. Maybe in the form of a Jonathan Pageau relief carving!

Here is an original Della Robbia:

I once wrote a feature on my blog, thewayofbeauty.org, on how houses in southern Spain have tiles containing geometric patterns set into the walls of their houses - a Christianization of the Islamic cultural inheritance, here: Geometric Tile Patterns in Andalusia.

Perhaps we could have a combination of the two ideas in which we start to have simple icon-corner triple sets set into such patterns? If done well, it could the house prices up - even if you are selling to an atheist, I suggest!

Just a thought.

Iconostasis, Rood Screen, Communion Rail, or Shag-Pile Carpetted Step

Are we creating a holy place, or fitting out the living room?

The nature of the dividing line between sanctuary and nave in a church has been a hot topic over the years. I raise the subject today not to spill yet more ink in complaining about the removal of altar rails in churches over the last 50 years or so, although it is something I do feel strongly about. Rather, I am interested in trying to establish how, with due regard for tradition, we might encourage in the Roman Rite a renewed engagement with art in the liturgy, in the such a way that it deepens our participation, rather than distracts from it.

Are we creating a holy place, or fitting out the living room?

The nature of the dividing line between sanctuary and nave in a church has been a hot topic over the years. I raise the subject today not to spill yet more ink in complaining about the removal of altar rails in churches over the last 50 years or so, although it is something I do feel strongly about. Rather, I am interested in trying to establish how, with due regard for tradition, we might encourage in the Roman Rite a renewed engagement with art in the liturgy, in the such a way that it deepens our participation, rather than distracts from it.

One thing that always strikes me when I go to an Eastern Rite Catholic Church, (recently I have been attending St Elias Melkite Church in Los Gatos, California,) is how much more naturally priest, deacon, cantor and congregation engage with the icons during the liturgy. In contrast, in the Roman Rite, even in traditional congregations, apart from perhaps the crucifix and altarpiece, the choice of art seems to be governed more by the priest’s personal devotion than liturgical considerations, and there appears to be very little engagement with it during the liturgy itself. At best, sacred art provides a decorative backdrop that helps set an appropriate mood for the worship of God with direct engagement in the liturgy itself, which is largely a hands-clasped and eyes-closed activity.

First a quick presentation of different options available to us.

According to my research, the original division in both East and West was more like today’s altar rail, with gaps or doors for processing. The typical “transenna” might have looked as this one at Sant’ Apollinarre in Ravenna, which I understand was restored in the 20th century.

Another example from the 12th century, at San Clemente in Rome, which seems to follow the early traditional style......

To read the rest of this article, go to blog.pontifex.university

Do We Need A New Christian Symbolism in Art - Aren't Pelicans and Peacocks Redundant?

Should we resurrect the old Christian symbolism? Or are pelicans and peacocks just nonesense, like cabbages and kings.

Should we resurrect the old Christian symbolism? Or are pelicans and peacocks just nonesense, like cabbages and kings.

Is there a danger that trying to reestablish traditional Christian symbols in art would sow confusion rather that clarity? Lots of talks and articles about traditional Christian art I see discuss the symbolism of the iconographic content; for example, the meaning of the acacia bush (the immortality of the soul) or the peacock (again, immortality). This is useful if we have a printed (or perhaps for a few of you an original) Old Master in church or a prayer corner as it will enhance our prayer life when contemplating the image. But is this something that we ought to be aiming to reinstate the same symbolism in what we produce today? Should we seek to educate artists to include this symbolic language in their art?  If symbols are meant to communicate and clarify, they should be readily understood by those who see them. This might have been the case when they were introduced – very likely they reflected aspects of the culture at the time – and afterwards when the tradition was still living and so knowledge of this was handed on. But for most it isn’t true now. How many would recognize the characteristics of an acacia bush, never mind what it symbolizes? If you ask someone today who has not been educated in traditional Christian symbolism in art what the peacock means, my guess is that they are more likely to suggest pride, referring to the expression, ‘as proud as peacock’. So the use of the peacock would not clarify, in fact it would do worse than mystify, it might actually mislead. (The reason for the use of the peacock as a symbol of immortality, as I understand it, is the ancient belief that its flesh was incorruptible). So to reestablish this sign language would be a huge task. We would not only have to educate the artists, but also educate everyone for whom the art was intended to read the symbolism. If this is the case, why bother at all, it doesn’t seem to helping very much, and in the end it will always exclude those who are not part of the cognoscenti . This is exactly the opposite of what is desired: for the greater number, it would not draw them into contemplation of the Truth, but push them out. I think that the answer is that some symbols are worth persevering with, and some should be abandoned. First, it is part of our nature to ‘read’ invisible truths through what is visible. This does not only apply to painting. The whole of Creation is made by God as an outward ‘sign’ that points to something beyond itself to Him, the Creator. Blessed John Henry Newman put it in his sermon Nature and Supernature as follows: "The visible world is the instrument, yet the veil, of the world invisible – the veil, yet still partially the symbol and index; so that all that exists or happens visibly, conceals and yet suggests, and above all subserves, a system of persons, facts, and events beyond itself.” It is important to both to make use of this faculty that exists in us for just this purpose; and to develop it, increasing our instincts for reading the book of nature and in turn, our faith.

If symbols are meant to communicate and clarify, they should be readily understood by those who see them. This might have been the case when they were introduced – very likely they reflected aspects of the culture at the time – and afterwards when the tradition was still living and so knowledge of this was handed on. But for most it isn’t true now. How many would recognize the characteristics of an acacia bush, never mind what it symbolizes? If you ask someone today who has not been educated in traditional Christian symbolism in art what the peacock means, my guess is that they are more likely to suggest pride, referring to the expression, ‘as proud as peacock’. So the use of the peacock would not clarify, in fact it would do worse than mystify, it might actually mislead. (The reason for the use of the peacock as a symbol of immortality, as I understand it, is the ancient belief that its flesh was incorruptible). So to reestablish this sign language would be a huge task. We would not only have to educate the artists, but also educate everyone for whom the art was intended to read the symbolism. If this is the case, why bother at all, it doesn’t seem to helping very much, and in the end it will always exclude those who are not part of the cognoscenti . This is exactly the opposite of what is desired: for the greater number, it would not draw them into contemplation of the Truth, but push them out. I think that the answer is that some symbols are worth persevering with, and some should be abandoned. First, it is part of our nature to ‘read’ invisible truths through what is visible. This does not only apply to painting. The whole of Creation is made by God as an outward ‘sign’ that points to something beyond itself to Him, the Creator. Blessed John Henry Newman put it in his sermon Nature and Supernature as follows: "The visible world is the instrument, yet the veil, of the world invisible – the veil, yet still partially the symbol and index; so that all that exists or happens visibly, conceals and yet suggests, and above all subserves, a system of persons, facts, and events beyond itself.” It is important to both to make use of this faculty that exists in us for just this purpose; and to develop it, increasing our instincts for reading the book of nature and in turn, our faith.  However, coming back to the context of art again, some discernment should be used, I suggest. I would not be in favour of creating an arbitrarily self-consistent symbolism. The symbol must be rooted in truth. The symbolism in the iconographic tradition is very good at following this principle. This is best illustrated by considering the example of the halo. This is very well known as the symbol of sanctity in sacred art. There are very good reasons for this. The golden disc is a stylized representation of a glow of uncreated, divine light, shining out of the person. Even if this were not already a widely known symbol, it would be worth educating people about the meaning of it, because in doing so something more is revealed. When however, the representation of a halo develops into a disc floating above the head of the saint, as in Cosme Tura’s St Jerome, or even a hoop, as in Annibale Caracci’s Dead Christ Mourned, (both shown) then it seems to me that the symbol has become detached from its root. Neither could be seen as a representation of uncreated light. These latter two forms, therefore, should be discouraged.

However, coming back to the context of art again, some discernment should be used, I suggest. I would not be in favour of creating an arbitrarily self-consistent symbolism. The symbol must be rooted in truth. The symbolism in the iconographic tradition is very good at following this principle. This is best illustrated by considering the example of the halo. This is very well known as the symbol of sanctity in sacred art. There are very good reasons for this. The golden disc is a stylized representation of a glow of uncreated, divine light, shining out of the person. Even if this were not already a widely known symbol, it would be worth educating people about the meaning of it, because in doing so something more is revealed. When however, the representation of a halo develops into a disc floating above the head of the saint, as in Cosme Tura’s St Jerome, or even a hoop, as in Annibale Caracci’s Dead Christ Mourned, (both shown) then it seems to me that the symbol has become detached from its root. Neither could be seen as a representation of uncreated light. These latter two forms, therefore, should be discouraged.

Similarly, those symbols that are rooted in the gospels or in the actual lives of the saints should be encouraged and the effort should be made, I think, to preserve or, if necessary, reestablish them. The tongs and coal of the prophet Isaias relate to the biblical accounts of his life. The inclusion of these, will generate a healthy curiosity in those who don’t know it, and so might direct them to investigate scripture. The picture shown, is one of my own icons.

In contrast consider the peacock and the pelican. The peacock, as already mentioned, does not, we now know, have incorruptible flesh. The pelican is a symbol of the Eucharist based upon the erroneous belief in former times that pelicans feed their young with their own flesh. My first though is that these symbols should not be used should not be used, because the reason for their symbolism in invalid, given that we no longer believe it to be true. However, I will admit that I am torn by the fact that both of these are beautiful and striking images, even if based in myth. Also, it might be argued, and this is particularly true for the pelican, that to use it is not resurrecting an obscure medieval symbol. It is an ancient symbol certainly - and St Thomas Aquinas's hymn to the Eucharist, Adore te devote called Christ the 'pelican of mercy'. But it lasted well beyond that. It was very widely understood even 50 years ago. Awareness of it is still common nowadays amongst those who are interested in liturgy and sacred art. Perhaps an argument could be made that even when the reason for the use of symbol is based in myth, if that is known and understood, and when that symbol recognition is still widespread enough to be considered part of the tradition, it should be retained. We should also remember that modern science is not infallible, and we moderns could be those who are mistaken about the pelican! My Googling research (admittedly even less reliable than modern science) revealed that the coat of arms of Cardinal George Pell has the image of the pelican. If this is so, I imagine he would have something to say about the issue also!

Our Lady of the Mount, Anjara, Jordan - a church and a story that reveals more of charism IVE

A mission parish of Argentinian order, Institute of the Incarnate Word (IVE), it commissioned four large new panel icons of the Mysteries of the Rosary; and is the place where in 2010, a statue of Our Lady wept tears of blood.

It is funny how one story leads to another, or perhaps I should say two others. I posted a recent article about my visit to the seminary of the Argentinian order Institute of the Incarnate Word (IVE) in Washington DC. First, I was contacted by English icon painter, Ian Knowles, who told me that this is the order that had commissioned him to paint icons of the Mysteries of the Rosary for a church run by them in Jordan. It is the Shrine of Our Lady of the Mount.

This was further evidence that the order is committed to the creation of beauty to evangelize the culture, as the description of their charism says, see here, item 5. I wanted to know more about the church and started to dig around. then I found out that it is also that it is the site of a miracle validated by the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, in which a statue of Our Lady wept tears of blood in 2010. The statue is old, perhaps 150-200 years old, and was purchased by the church shortly before the miracle occurred. In 2014, fellow Argentinian, Pope Francis visited the site of the Baptism of Our Lord in the Jordan and the occasion was marked by a gift from IVE of an image of Our Lady of Anjara.

Culture, beauty, prayer and devotion to Our Lady, all aspects of the charism of the order and somehow all of this is entwined in a dynamic mix for the mission of the Church in this one shrine in the Middle East.

For the icons, there are some photos below at the bottom of the blog post. Immediately below is artist Ian with one of the panels in progress (who incidentally I met several years ago when we both attended a class taught by Aidan Hart!) .

I am so heartened to hear of IVE wanting to encourage 'eyes-open prayer' through the commission of these icons. It shows, in my opinion, a true understanding of the New Evangelization as, regardless of the miracle, the simple beauty of each in the church, will encourage a deeper prayer that engages the whole person. This will facilitate a supernatural transformation of the person in Christ and lead, in turn, to the transformation of the culture as each person contributes to it, gracefully and beautifully by simply going about their daily business.

The same can be said of the statue. For all the headlines in connection with the miracle (which I very happy to accept occurred), it is the supernatural transformation of mankind in Christ - partaking of the divine nature - that is the truly astounding fact of the Christian faith; and this is an extraordinary privilege that is open to every single human person and leads to a life of such joy. Sometimes it needs the exceptional, headlining events such as miracles, to inspire the prayer that will engender what I think are the greater, yet so often neglected and misunderstood truths of the Faith.

The account of the miracle is on the National Catholic Register, here. The account of the Pope's visit is on the IVE site, here. The order is devoted to Our Lady with a special devotion to the Immaculate Conception and Our Lady of Lujan, a South American holy image. What struck me in the account is how Argentinian priest of the order Fr Nammat says quite matter-of-factly that he doesn't know why the miracle should have occurred, except to remark that the 'Arab spring', which began the persecution of so many Christians (and Muslims) in the region began shortly afterwards, and perhaps there is a connection.

Below: Ian's Sorrowful Mysteries, with detail below that.

..and the Joyful Mysteries:

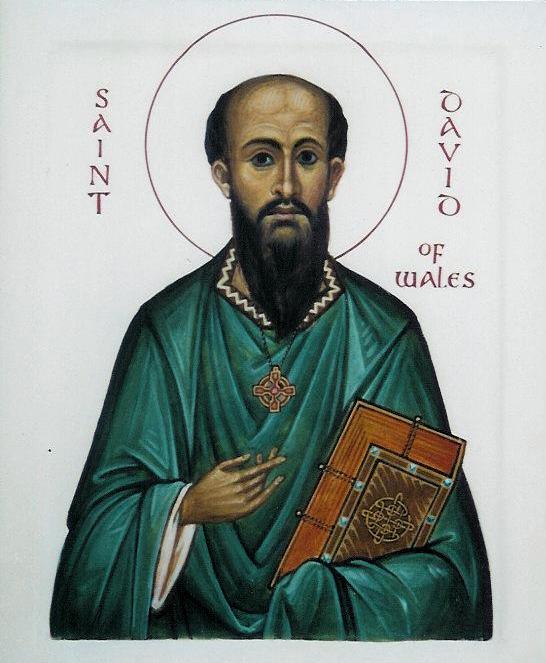

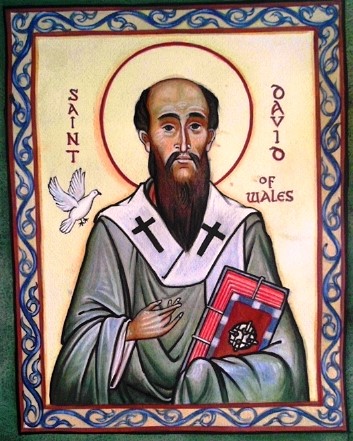

New icon, St David of Wales

This is painted in egg tempera on watercolour paper. I have based it, on another of Aidan Hart's icons of early British saints. He has done a series of similar ones to this, but I don't know if this is his own prototype or if he drew inspiration from another source. Regardless, I love his work and very often look to his corpus first when considering how to approach a subject.

This is in my icon corner at home and I noticed this morning that his right eyelid, the left as you look at it, is drooping slightly. I'll have to modify it.

This is one of the drawbacks of painting for you own prayer, you can be distracted by your own errors! Here is Aidan's:

New icon: St Edna, Abbess of Whitby

This recently painted icon is St Edna, who succeeded St Hilda as the Abbess of Whitby in the 7th century. I based this icon a series painted by Aidan Hart of early British saints, including one of St Hilda herself. These seem to me, in turn, to be inspired by an icon of St Theodora from Mt Sinai in Egypt. This is for my domestic church.

How do we paint disfigurement and bodily imperfections in saints?

Blessed Margaret of Castello is the patron saint of unwanted and disabled children. Born in 14th century Italy, she was disfigured and neglected from birth by her wealthy parents. She was taken in by Dominican nuns when she was sixteen and became a third order Dominican. Her story is both harrowing and inspiring: harrowing because of the suffering and cruelty she experienced; and inspiring because of her joy in life, which arose from her faith and transcended that suffering. Here is an account of her life from the website of the Dominican sisters at Nashville. As I read this story it occured to me that if this had been today and her parents had had access sonogram prior to her birth she would surely have become another abortion statistic.

A friend of mine, Gina Switzer, told me that she had been commissioned to paint her and we were discussing how artists might represent human disfigurement in saints so that they retain the dignity of the human person. So this week, I thought I'd write about this - for those who are looking for the continuation of the series, we'll come back to the series of architecture videos next week.

The first point is that it is not immediately clear that human imperfections should be portrayed in holy images. One might assume that these are absent in heaven and so to the degree that we show the redeemed person, argue that they should not be there at all. I was reminded that Denis McNamara told me recently that when they were designing the stained glass windows for the new John Paul II chapel at Mundelein, they thought about this and deliberately left out St Maximilian Kolbe's spectacles for just this reason.

The counter to this is that in order to make an image worthy of veneration, according to the theology of holy images established by St Theodore the Studite in the 9th century, two things need to be present: first the name should be written on the image; and second it should portray the essential visual characteristics of the saint. This last criterion refers to those aspects of the saint that together give the person his unique identity. This can include a physical likeness, although a rigid application of physical likeness is not appropriate - a holy image is not a portrait. We are thinking here of those things that characterize the person and his story, for example, St Paul's baldness, the tongs containing hot coal for Isaias. With this in mind, to use the example of the JPII chapel again, Denis told me that for Blessed Teresa of Calcutta they did want to show her deformed feet because it symbolized her charity - this disfigurment arose because she always chose the worst shoes for herself from those donated to the order. We thought that for St Margaret, in this age of the culture of death, the portrayal of her joyful but with her physical imperfections would be particularly important.

One ideas was to look for inspiration at the dwarfs painted by Velazquez from the court of Philip IV of Spain, who have great dignity and bearing. This idea was rejected, firstly because they can also have an imappropriate haughtiness about them which would have to be changed. And second, because to incorporate all of these considerations into a naturalistic style and be able to pull it off would be very difficult indeed - it might almost require a Velazquez to do it. Even in naturalistic styles there should always be a degree of symbilism (or idealism) and this is notoriously difficult for contemporary Catholic artists to get right even for easier subjects. (Below you see his portrait of Sebastien de Morro.)

In the light of all these considerations I thought that I would probably paint an image in a gothic or iconographic style in which her natural physical characteristics were shown, retained but nevertheless redeemed in some way. The first thing I always do is, as I was taught, look first at existing images and if I can find one that is appropriate, just copy it. The aim to change as little as possible. If there is no perfect image to copy then I look at other images from which I can use the particular characteristics that appear to be missing from my desired image and patch them together into a single image. Only if I can find nothing that has already been painted do I attempt something original. I create drawings made from observation of nature and onto those I impose the stylistic form of the tradition that I am working in.

I found this picture of this sculpture of St Margaret.

I thought that a painting in egg tempera based upon this would work. A change I would make, I though, would be to change the face to one that is more joyful. I like the ones that I see in a series of Aidan Hart's icons, such as St Winifride or St Hilda of Whitby or St Melangell, which look to me as though they are based on an ancient icon of St Theodosia which is at Mt Sinai. You can see images of each below. One thing that I would do is close her eyes to indicate St Margaret's blindness: