Should We Paint God the Father?

One of the most famous pieces of sacred art that exists is Michelangelo’s fresco, in the Sistine Chapel, of God giving the spark of life to Adam. Despite its popularity and familiarity, I had often wondered about the validity of representing God the Father.

My own instincts run against the idea of portraying God the Father in a painting at all, even when I was a child (I always thought that the white-whiskered God looked more like God the Grandfather, than God the Father). Later on in life, this was reinforced by the fact that my icon painting training led me to believe that it was wrong. I was pretty sure, but not certain, that it was not part of the tradition. Certainly, I have never painted an icon of God the Father. Furthermore, the theology of Theodore the Studite in regard to sacred imagery, which is accepted by both Eastern and Western Churches, bases the argument for the creation of any figurative art upon the fact that we can portray the person of Christ as man. The person of God the Father is a spiritual being and most certainly not man. This would seem to suggest that we should not portray the Father as man either.

One of the most famous pieces of sacred art that exists is Michelangelo’s fresco, in the Sistine Chapel, of God giving the spark of life to Adam. Despite its popularity and familiarity, I had often wondered about the validity of representing God the Father.

My own instincts run against the idea of portraying God the Father in a painting at all, even when I was a child (I always thought that the white-whiskered God looked more like God the Grandfather, than God the Father). Later on in life, this was reinforced by the fact that my icon painting training led me to believe that it was wrong. I was pretty sure, but not certain, that it was not part of the tradition. Certainly, I have never painted an icon of God the Father. Furthermore, the theology of Theodore the Studite in regard to sacred imagery, which is accepted by both Eastern and Western Churches, bases the argument for the creation of any figurative art upon the fact that we can portray the person of Christ as man. The person of God the Father is a spiritual being and most certainly not man. This would seem to suggest that we should not portray the Father as man either.

I quietly suspected that the white-bearded God of Michelangelo or William Blake or even my favourite baroque artist Velazquez were all in error, his Crowning of the Virgin by the Trinity is to the right. I wasn't too worried about Blake, an eccentric non-Catholic, but Michelangelo and Velazquez?

I quietly suspected that the white-bearded God of Michelangelo or William Blake or even my favourite baroque artist Velazquez were all in error, his Crowning of the Virgin by the Trinity is to the right. I wasn't too worried about Blake, an eccentric non-Catholic, but Michelangelo and Velazquez?

I was approached recently to do a commission that involves the portrayal of the Father. Rather than reject it out of hand, I thought I had better find out where the Church stands on this.

Here’s what my first investigations have revealed. For the first thousand years or so of Christianity, East and West, there was little portrayal of the Father figuratively. Then images started to appear in both the Eastern and Western traditions, though it was more common in the West.

There are two simple arguments that I have found for the representation of the Father: the first is that Christ said in John 14:9 that whoever has seen me has seen the Father. This would seem to open up to a representation of the Father as the Son. So, one could say, seeing an image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus is also seeing one of the Sacred Heart of the Father, with the heart of the Father understood as a symbol of His love.

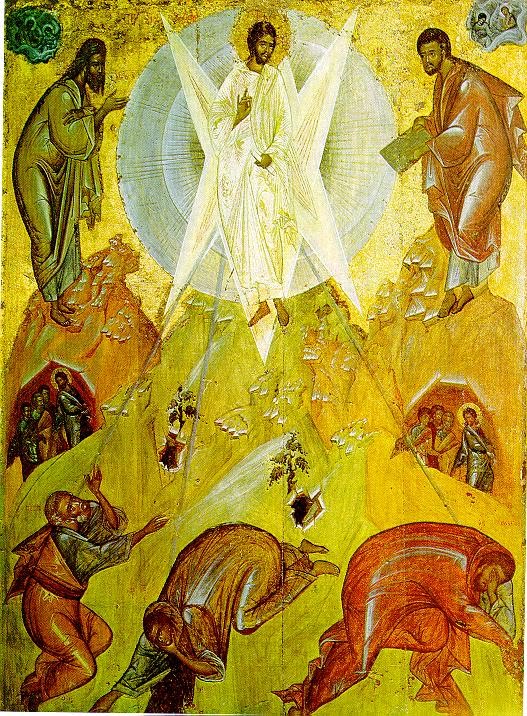

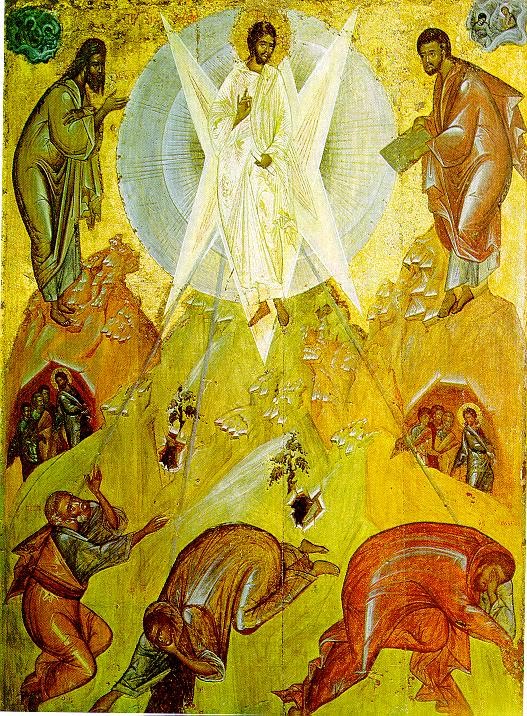

![]() The second is that the white-bearded figure, which we are all familiar with is the Ancient of Days in the book of Daniel (7:9, 13, 22). This is the source of so many familiar portrayals of the Father. In the East there is a tradition known as the New Testament Trinity. This title would distinguish it from the Hospitality of Abraham (in which three angelic strangers represent the three persons of the Trinity). Right is a Greek Orthodox New Testament Trinity from the ceiling of the entrance Vatopedion Monastery at Agion Oros (Mount Athos), Greece. The Catholic Church, allows for the interpretation of the Ancient of Days as the Father, which justifies the portrayal of the Father. (I have been told that Pope Benedict XIV [fourteenth, not sixteenth!] in 1745 pronounced this, though beyond a Wikipedia reference I have not been able to validate this). It also allows for the interpretation of the Ancient of Days as Christ. The Russian Orthodox Church, since the synod of Moscow in 1667 has forbidden the portrayal of God the Father as a man. Consistent with this it interprets the Ancient of Days strictly as the Son. It is this decision of the pronouncement by the Russian church that gave me the idea, wrongly, that it had never been part of the Eastern tradition and that the whole present Eastern Church forbids it.

The second is that the white-bearded figure, which we are all familiar with is the Ancient of Days in the book of Daniel (7:9, 13, 22). This is the source of so many familiar portrayals of the Father. In the East there is a tradition known as the New Testament Trinity. This title would distinguish it from the Hospitality of Abraham (in which three angelic strangers represent the three persons of the Trinity). Right is a Greek Orthodox New Testament Trinity from the ceiling of the entrance Vatopedion Monastery at Agion Oros (Mount Athos), Greece. The Catholic Church, allows for the interpretation of the Ancient of Days as the Father, which justifies the portrayal of the Father. (I have been told that Pope Benedict XIV [fourteenth, not sixteenth!] in 1745 pronounced this, though beyond a Wikipedia reference I have not been able to validate this). It also allows for the interpretation of the Ancient of Days as Christ. The Russian Orthodox Church, since the synod of Moscow in 1667 has forbidden the portrayal of God the Father as a man. Consistent with this it interprets the Ancient of Days strictly as the Son. It is this decision of the pronouncement by the Russian church that gave me the idea, wrongly, that it had never been part of the Eastern tradition and that the whole present Eastern Church forbids it.

There is a Western tradition of portrayal of the trinity in a type known as the Throne of Mercy, in which the Father sits on his throne and presents his crucified son to the viewer while a dove rests on the cross or hovers just above it. It was this that was explicitly mentioned by Benedict XIV. A 16th century German version is shown left. This tradition goes right back the Medieval times in the Western Church and we have this continued even into the 20th century with Eric Gill in England doing woodcut of this image in a modern gothic style.

There is a Western tradition of portrayal of the trinity in a type known as the Throne of Mercy, in which the Father sits on his throne and presents his crucified son to the viewer while a dove rests on the cross or hovers just above it. It was this that was explicitly mentioned by Benedict XIV. A 16th century German version is shown left. This tradition goes right back the Medieval times in the Western Church and we have this continued even into the 20th century with Eric Gill in England doing woodcut of this image in a modern gothic style.

So where do I stand on this now? Clearly the portrayal of the Father as a grey-haired man is permitted. I would feel on safest ground following the traditional presentations, such as the Mercy Throne image. Outside that, I would be consider images, but would be cautious, unwilling to promote, as Caroline Farey of the School of the Annunciation put it to me, ‘any trend of anthropomorphizing God the Father in case the transcendence of God is further compromised in people's imaginations.’

It is worth pointing out also, that when God is portrayed as a single person in the form of the Ancient of Days, we cannot be sure that it is the Father who is portrayed. The artist might, quite justifiably, have the intention of representing the Son. I have not, for example, been able to find an authoritative text that tells us precisely which person of the Trinity either Michelangelo or Blake intended us to be looking at (I would welcome comments from readers on this point).

Below: an early gothic Mercy Throne; a 20th century version by the Englishman, Eric Gill; an early gothic pieta in which God the Father supports the son; a baroque Mercy Throne by Ribera, 17th century; and William Blake's Ancient of Days.

Thanks to reader Walter who gave me a link through to an article in the

Thanks to reader Walter who gave me a link through to an article in the

There have been a number of articles published recently, following a show in Moscow, of carved icons of a Russian couple

There have been a number of articles published recently, following a show in Moscow, of carved icons of a Russian couple

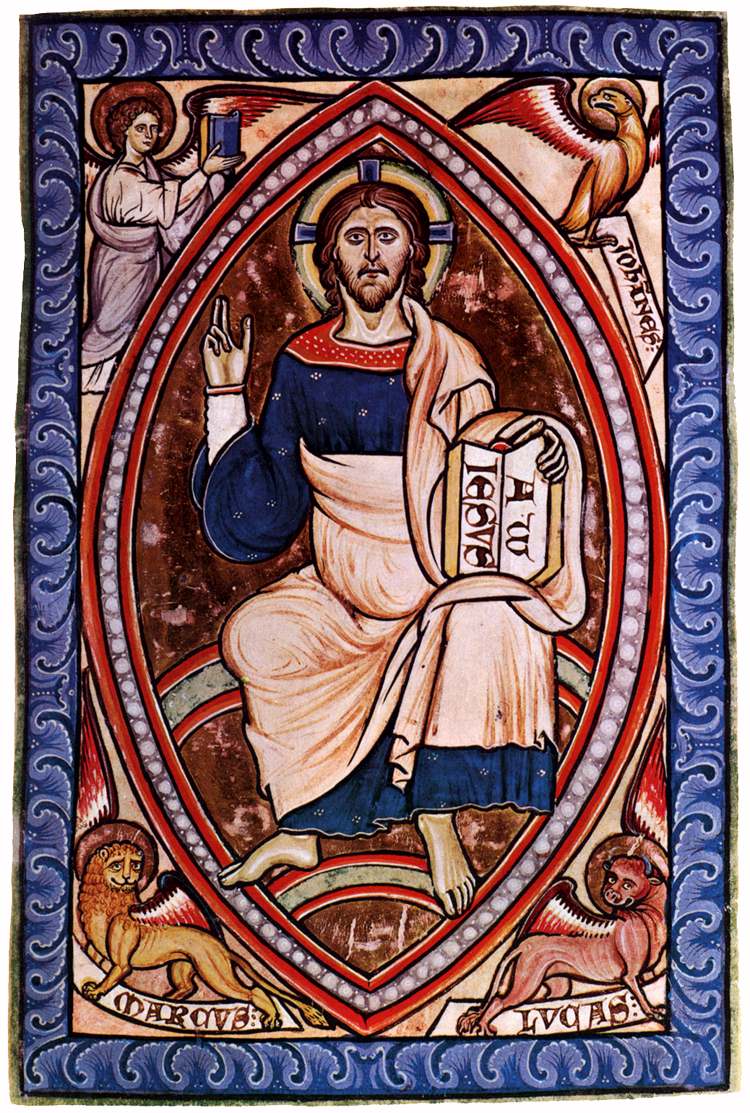

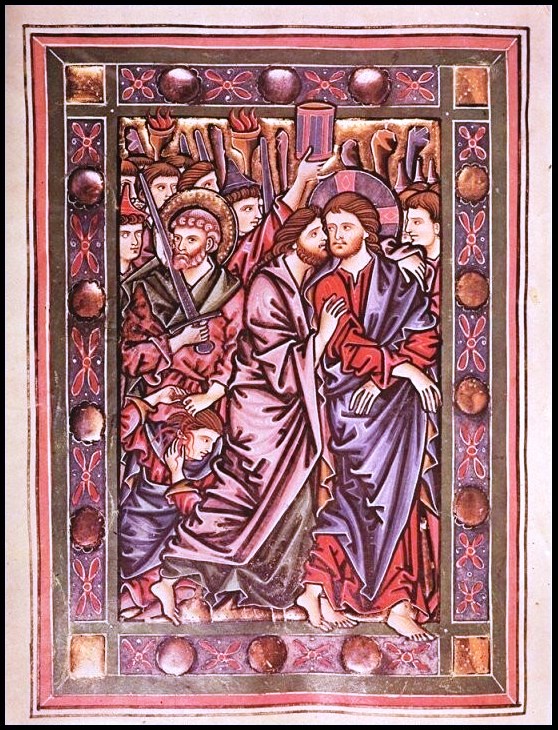

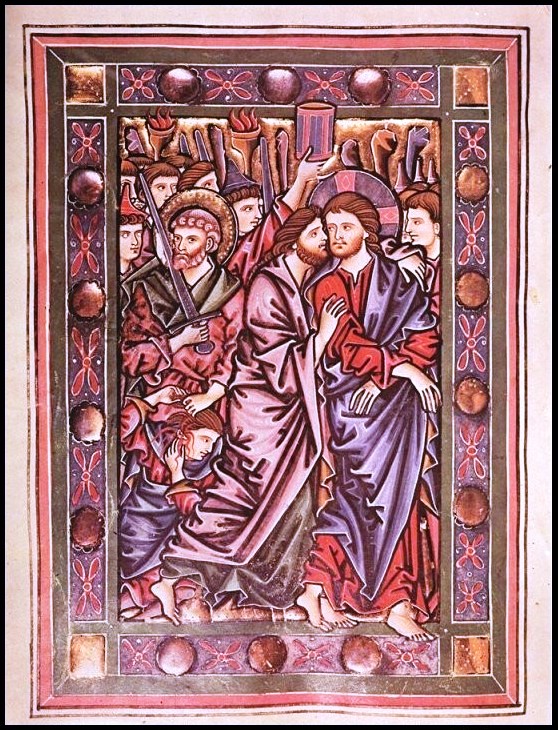

Here's some more work from the summer painting course I taught in Kansas City, Kansas at the Savior Pastoral Center Kansas. It was sponsored by the Diocese of Kansas City, Kansas which runs the center. I thought I would show some of the work done by students. This is unusual in that we focussed on 13th century gothic illuminated manuscripts from the School of St Albans. The original is shown top left and the work of the class below. Apologies to those whose work isn't featured - I really haven't deliberately cut anyone out. For some reason I didn't arrive home with photographs of everybody's work.

We have already booked up to do two more courses next summer, so those who are interested might even contact the center now. This year the places went quickly and we could have filled the class more than twice over. The center website is

Here's some more work from the summer painting course I taught in Kansas City, Kansas at the Savior Pastoral Center Kansas. It was sponsored by the Diocese of Kansas City, Kansas which runs the center. I thought I would show some of the work done by students. This is unusual in that we focussed on 13th century gothic illuminated manuscripts from the School of St Albans. The original is shown top left and the work of the class below. Apologies to those whose work isn't featured - I really haven't deliberately cut anyone out. For some reason I didn't arrive home with photographs of everybody's work.

We have already booked up to do two more courses next summer, so those who are interested might even contact the center now. This year the places went quickly and we could have filled the class more than twice over. The center website is

I was contacted recently by a reader, a priest who had concelebrated a Station Mass at San Marco di Campidoglio in Rome.

I was contacted recently by a reader, a priest who had concelebrated a Station Mass at San Marco di Campidoglio in Rome.