This is the second of two posts featuring meditations on frescoes painted by Fra Angelico on the walls of the cells at San Marco monastery in Fiesole, near Florence, by Br John Paul Puschautz, a Dominican of the Western Province in the US. Last time, we featured his meditation on the Annunciation. This week it is the Mocking of Christ

A Meditation on Fra Angelico's Annunciation by Brother John Paul Puschautz O.P.

Mystical Mary: The Enduring Mystique of the Mother of God

A Classic Book on Art and Beauty to Be Republished: The Beauty of Holiness and the Holiness of Beauty

The Red Cross as a Symbol of the Resurrection

As we move into the second week of Easter, here is a symbolic image of the Resurrection. It has been embroidered onto a chalice pall, recently commissioned by a priest.

In the words of the patron to the artist when he commissioned the pall:

It depicts the Blood the Lamb, but not into a chalice — which I think would be good for a pall. No reason to have an image of a chalice atop a chalice - that’s the sort of “multiplication of images” that detracts from the Sacred Liturgy. I like this image of the Lamb, the Blood, but no chalice.

The image of the shell and the water (of Baptism) at the top is very meaningful. “From the Savior’s side flowed blood and water, the fountain of the sacramental life of the Church.” We often forget the saving waters. And both wine and water are poured into the chalice. Good imagery for a pall.

The lamb is the sacrificial victim, 'standing as if slain' from Chapter 5 of the Book of the Apocalypse, and the Resurrection is symbolized by the banner with a red cross on a white background. I am not clear as to precisely how the red cross became the symbol of the Resurrection. From what I can gather, the symbol of the cross, in various colors became popular in northern Italian cities from about 1000AD and they would carry these banners with them on the crusades to the Holy Land that took place in the following centuries. It became associated with St George in the late middle ages, as St George became a patron of the crusader knights. It was linked particularly with the Resurrection in the West around this time too.

Since the time of Constantine, who ordered an image of the Christian cross to be put on the Roman Standard as he went into battle and was victorious, the Holy Cross has been a symbol of both spiritual and temporal battles against those who wish to destroy the Church in both East and West. An ancient hymn sung to commemorate the Feast of the Holy Cross in the Eastern Churches runs as follows:

Oh Lord save Your people and bless Your inheritance, grant victory to our country over its enemies and preserve your community by the power of your Cross.

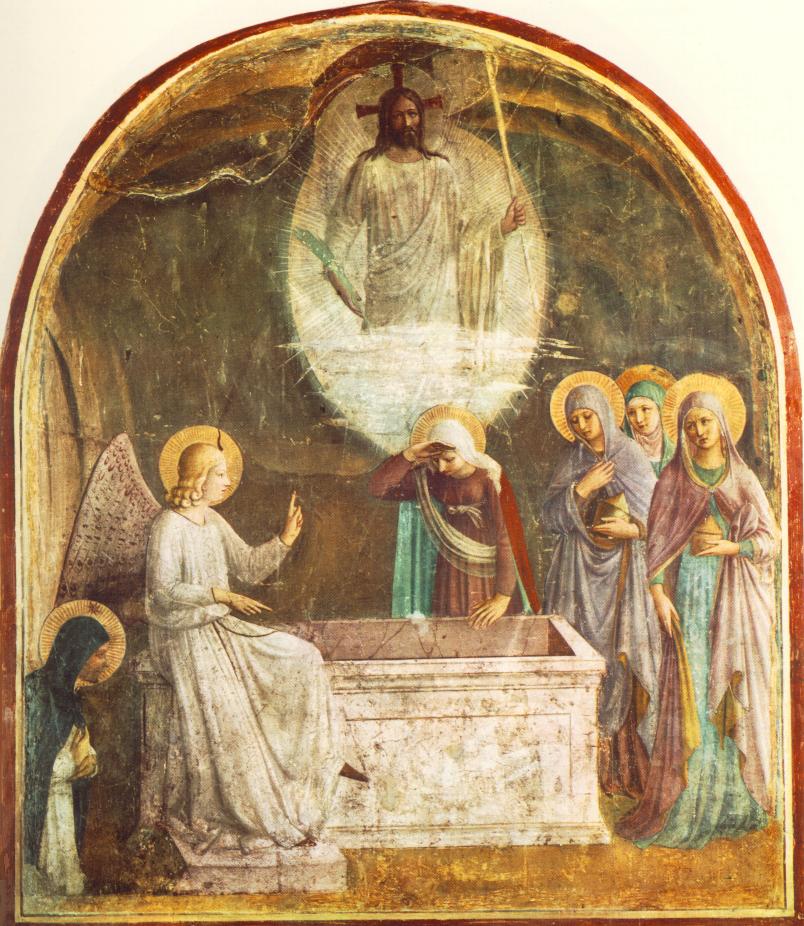

When I was looking for other images of this symbol, I remembered that Fra Angelico used it in his portrayal of the Resurrection:

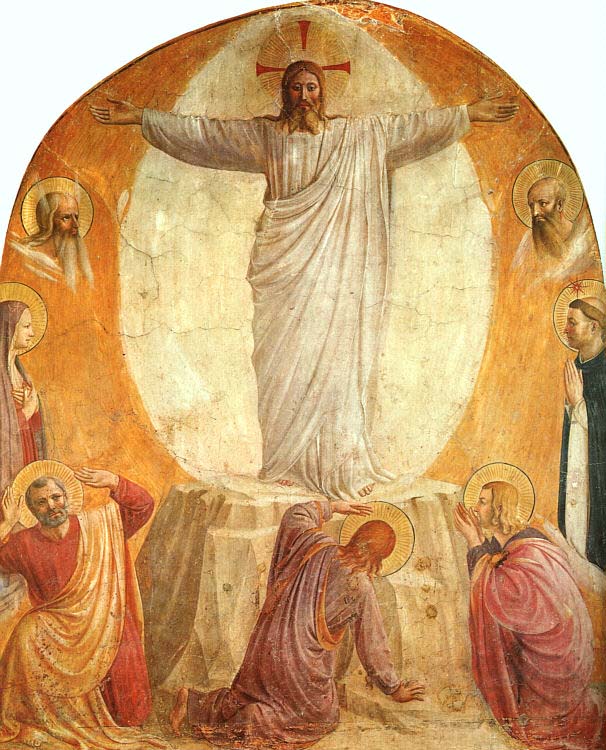

I was reminded in looking at both of the images the halo of Christ contains a red cross too. There is no consistently used color for the cross of the halo in Christian symbolism. The color red is used by Fra Angelico frequently, however, and so I am guessing that in each case the artist deliberately placed these two symbolic representations close to each other so that we would see the connection. Here is Fra Angelico's Transfiguration.

The artist who created the pall, incidentally is Kathryn Laffrey, kl-artstudio.com, who is based in Michigan and is currently a student on the Master of Sacred Arts program at Pontifex University.

A Question for Way of Beauty Readers

Recently a reader contacted me with a question about Fra Angelico's fresco of the Last Supper. Is there a particular reason why some of the figures are kneeling and others not? And who is the female figure present? In answer to the first, I assumed that he was emphasising that the Last Supper is the Mass I don't know if there is any tradition that governs who knelt and who sat. (I find it interesting that Judas, with the black halo is kneeling in line.) I guessed that the lady present is Our Lady (or perhaps Mary Magdalene) but didn't really know. Ordinarily the names would be present (in accordance with the theology of Theodore the Studite from the 9th century). So this is an additional question: does anybody know who she is and also, do you know if Fra Angelico put the names of those portrayed somewhere as part of this painting? If not I would be interested to know why not as names are necessary to make an image worthy of veneration.

I posed these questions on the New Liturgical Movement blog also, so I am curious to see how the answers of the two readerships varies!

Recently a reader contacted me with a question about Fra Angelico's fresco of the Last Supper. Is there a particular reason why some of the figures are kneeling and others not? And who is the female figure present? In answer to the first, I assumed that he was emphasising that the Last Supper is the Mass I don't know if there is any tradition that governs who knelt and who sat. (I find it interesting that Judas, with the black halo is kneeling in line.) I guessed that the lady present is Our Lady (or perhaps Mary Magdalene) but didn't really know. Ordinarily the names would be present (in accordance with the theology of Theodore the Studite from the 9th century). So this is an additional question: does anybody know who she is and also, do you know if Fra Angelico put the names of those portrayed somewhere as part of this painting? If not I would be interested to know why not as names are necessary to make an image worthy of veneration.

I posed these questions on the New Liturgical Movement blog also, so I am curious to see how the answers of the two readerships varies!

I found two other Last Supper images by Fra Angelico. One has keeling figures. The Latin inscription gives the connection with the wording of the Mass (I'm at my limits on Latin here, so please correct/translate anyone who is inclined!). Neither has a female figure.

What Does It Look Like When We Participate In Christ's Glory through the Liturgy?

The Transfiguration as a symbol of the liturgy and our participation in the glory of Christ

As I have written before, I recently read Jean Corbon's book The Wellspring of the Worship. In it Fr Corbon describes how an ordered participation in the liturgy opens our hearts in such a way that we accept God's love and enter into the mystery of the Trinity; in which we worship the Father, through the Son in the Spirit. This renews and transforms us so that we are rendered fruitful for God by participating in the glory of Christ. Some who read this might wonder what this glory as manifested in the people of the Church looks like. Can we really see people shining with light? I have not seen one person shining with light that I am aware of, so does that mean that none of my Christian friends are properly participating in the liturgy?

The Transfiguration as a symbol of the liturgy and our participation in the glory of Christ

As I have written before, I recently read Jean Corbon's book The Wellspring of the Worship. In it Fr Corbon describes how an ordered participation in the liturgy opens our hearts in such a way that we accept God's love and enter into the mystery of the Trinity; in which we worship the Father, through the Son in the Spirit. This renews and transforms us so that we are rendered fruitful for God by participating in the glory of Christ. Some who read this might wonder what this glory as manifested in the people of the Church looks like. Can we really see people shining with light? I have not seen one person shining with light that I am aware of, so does that mean that none of my Christian friends are properly participating in the liturgy?

The answer to this might come through consideration of Corbon's description of the symbolism of the icon of the Transfiguration. It is an icon of the liturgy.

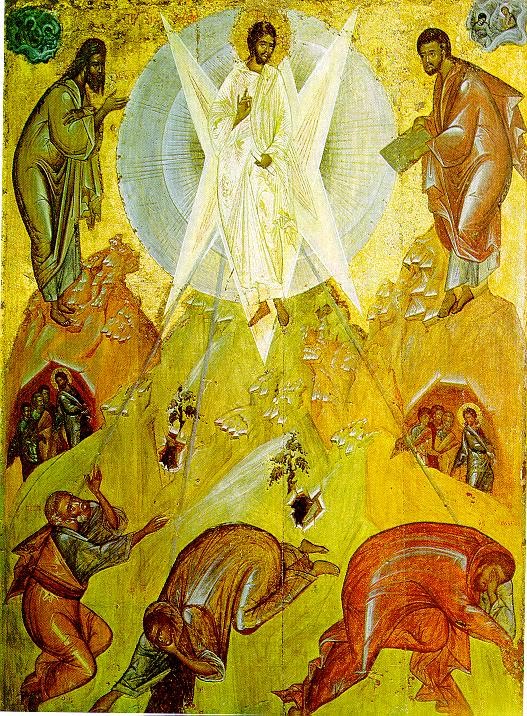

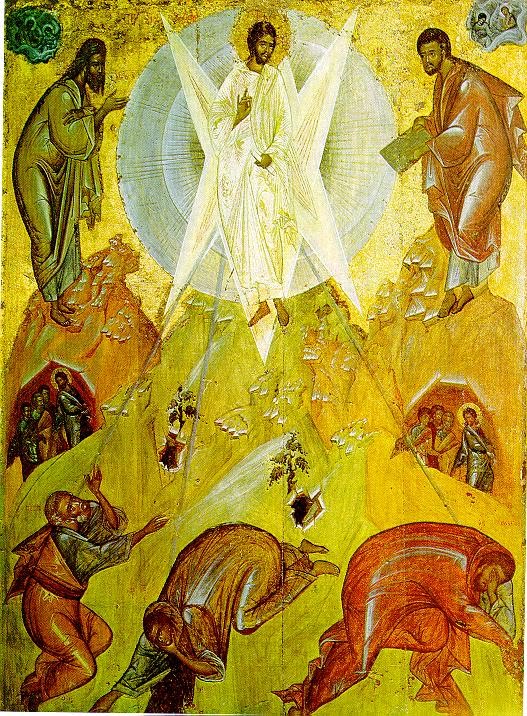

At one level the icon of the Transfiguration portrays, of course, the events as they happened in the bible. The composition of the icon shown above, by Theophanes the Greek, is ordered to Christ. He is flanked by the prophets Moses and Elijah who bow reverently. His appearance changes so that he and his clothing shine with uncreated light. Peter on the left is shown talking to Christ, he and the others all looking disoriented by what they are seeing and hearing. Three rays extend to the ears of the apostles as they hear the voice of the Father.

The biblical description of the Transfiguration, says Corbon, point not only to Christ's transfiguration but also to our own through participation in the liturgy. Through the liturgy, he says, the Church becomes the 'sacrament of communion between God and man' and as members of the mystical body of Christ we we partake of the divine nature becoming 'God as much as God becomes man' (quoting Maximus the Confessor). We participate in this glory. The disciples see Christ because they are raised up also in purity, symbolised by their going up the mountain. This enables them to see and to hear the divine light and voice. In this life we too by degrees, through our participation in the liturgy and participate in this glory and ascend the holy mountain. The complete transformation does not take place until the next life.

For Corbon, there is a threefold manifestation taking place here. First the revealing of Christ, second the purification of the hearts that enable us to see and grasp the truth; third and finally 'if we are given the gift of "believing in his name" and if we have received "power to become sons of God" (Jn 1:12), it is in order that he may send us into the world as he himself was sent by his Father. His Spirit gives us a new birth in order that his glory may be manifested to others through us and that they in turn may be transformed into the body of the Lord. This final extension of the life giving light is intended to communicate the reality that is the body of Christ and introduce into communion with it the scattered children of God.

For Corbon, there is a threefold manifestation taking place here. First the revealing of Christ, second the purification of the hearts that enable us to see and grasp the truth; third and finally 'if we are given the gift of "believing in his name" and if we have received "power to become sons of God" (Jn 1:12), it is in order that he may send us into the world as he himself was sent by his Father. His Spirit gives us a new birth in order that his glory may be manifested to others through us and that they in turn may be transformed into the body of the Lord. This final extension of the life giving light is intended to communicate the reality that is the body of Christ and introduce into communion with it the scattered children of God.

This tells us how that in order to be agents of evangelisation, we must shine with the light of glory and it is through our ordered and active participation in the liturgy. 'If we consent in prayer to be flooded by the river of life, our entire being will be transformed: we will become trees of life and be increasingly able to produce the fruit of the Spirit : we will love with the very Love that is our God...This process is the drama of divinisation in which the mystery of the lived liturgy is brought to completion in each Christian'.

So do we really shine with light? I have never seen anyone shining like Christ as portrayed in these examples of the Transfiguration. If what Corbon says is true, one might at least expect to see a few halos or feint light of partial divinisation occasionally, if not full-blown transfiguration. I fact, I feel I probably have seen saintly people without knowing it. The fact that I do not see the light of glory in them is as much a reflection on me as the people I have met.

When I was learning to paint icons, my teacher who was an Orthodox monk told me a story that explains this. I cannot remember the detail but the essence of it was this: two saints met and as they spoke to each other, each saw the other shining with halos of uncreated light. They were both amazed and later described what they had seen to a third party. On hearing the tale from each one, the third party realised what was happening, that each was a holy man, shining with the uncreated light but unaware of it. Because of their holiness and purity they were able to see the uncreated light of the other. The third person, who knew both, could not see the light in either.

If this is the extent of it, then it doesn't help us much, for only the holy, the already converted, are open to being conversion because they are the only ones who can see the light of glory. However, through God's grace there are other ways that we grasp with our inner eye of faith the glory that shines out of those we meet. In my own conversion there are a number of things that brought me to the Church. One was the beautiful liturgy of the Brompton Oratory. But it was also the examples of the people that I met who had an effect on me: their conduct, the glint in their eye, the sense of peace, the dignity and calm with which they went about their business. Although they didn't speak of their Catholicism much - just the occasional reference to it - I somehow knew that these qualities in them. This drew me to them and because I wanted these things too, to the Church which was the source. Christ's glory was shining through them. It was one of these people who, in a matter-of-fact way suggested that I might like to visit a church in South Kensignton one Sunday 'but make sure you go to the eleven o'clock,' he said. I didn't know it, but he was directing me to Solemn Mass at the Oratory.

Corbon is telling me how I can be one of these people who is an agent of transformation in the lives of others. Because society is the vector sum of personal relationships, this is the answer to the transformation of society as well. In the final slim but powerful chapter of the book he describes how this is the answer to the transformation of every aspect of the culture, including even economics and injustice in the workplace (I was amazed by this and wrote about it in my blog here).

The second painting is by Fra Angelico. Interestingly in this St John is the one shown looking directly at Christ. One wonders if perhaps Fra Angelico is indicating that John has that purity of heart that enables him to look directly at the Lord. St Augustine tells us (cf Office of Readings, Saturday after Ascension) that the Church knows two lives: one is through faith, the other through vision; one is passed on pilgrimage in time, the other in our eternal home; one is life of action, the other of contemplation. The apostle Peter personifies the first life, John the second. Maybe this is what Fra Angelico is trying to communicate to us.

A Recommended Book for Young Children

Here is a book introducing young children both to an aspect of the Faith and to the artistic traditions of the Church. It is not an unusual idea - there are other books for children making use of the works of Old Masters. However, this one caught my eye because it uses exclusively the art of one artist, Fra Angelico, which gives the project greater cohesion than many. Also, I love Fra Angelico, so anything that introduces his art to children is worth looking at in my opinion.

Bethlehem Books, the publisher, says that this is 'a first board book in a set on the Blessed Trinity. The aim of The Saving Name of God the Son is to help guide the child listener and adult reader into the mystery of the Son of God, Jesus Christ'

Here is a book introducing young children both to an aspect of the Faith and to the artistic traditions of the Church. It is not an unusual idea - there are other books for children making use of the works of Old Masters. However, this one caught my eye because it uses exclusively the art of one artist, Fra Angelico, which gives the project greater cohesion than many. Also, I love Fra Angelico, so anything that introduces his art to children is worth looking at in my opinion.

Bethlehem Books, the publisher, says that this is 'a first board book in a set on the Blessed Trinity. The aim of The Saving Name of God the Son is to help guide the child listener and adult reader into the mystery of the Son of God, Jesus Christ'

There are ten described events, including The Resurrection, below, and with the front cover this makes 11 reproductions. There are very few words, perhaps two or three short sentences per picture, but they are taken from Scripture or the Catechism and it has been put together so that it runs smoothly, simply and understandably. Given the source of the text and the quality of the reproductions, I can imagine that it is likely to give the grown-ups doing the reading a resource for some pictorial lectio. At the back are comprehensive details about each picture (name, location of original etc) and the sources for the accompanying text, plus scriptural readings and sections of the Catechism that reinforce the theological point being made.

To get more information or order The Saving Name of God the Son, go to Bethlehem Books website, here. Bethlehem Book publish this as part of their Holy Child teaching curriculum and present many ideas about how to use this book with different age groups to maximise the enjoyment and the quality of the educational experience, here.

There is an additional exercise that I would encourage. If parents encourage their older children to copy these beautiful images as best they can then it will impress the style of this wonderful artist upon their souls in some way and, who knows, it might stimulate a future Fra Angelico to realise his or her vocation!

The Symbolism in the Content of Fra Angelico's Frescoes

The Sermon on the Mount Rather than talking about form, my usual interest in painting, I thought that this time I would focus on the symbolism of the content contained in an example of gothic art by focusing on a fresco of the Sermon on the Mount, once again by Fra Angelico (1395-1455). It is in cell 32 in the north wing of San Marco in Florence and was painted between 1440 and 1450. I should mention that I am indebted to a lecture given by Dr Lionel Gracey who was my colleague when I was teaching at the wonderful Maryvale Institute in Birmingham, England for much of the detailed information here.

First of all there is the symbolism of the colours of Jesus’s clothes. The red under garment or tunic is red, which is a symbol of blood and a sign of his humanity; while the blue outer garment or cloak symbolizes his divinity. I was told that originally in this fresco the blue of the cloak matched precisely the heavenly blue of the sky. Fra Angelico often uses this colour symbolism for Christ and it is seen in all three liturgical traditions (although it is certainly not true to say that depiction of Christ is limited to these colours). Shown below is the Last Supper of an earlier gothic master, Duccio; a modern icon of Christ by Gregory Kroug, the 20th century Russian émigré; and The Kiss of Judas by Caravaggio from the early 17th century. All have the same colour scheme for Christ's robes. Judas is depicted in Fra Angelico’s painting as well, indicated by the black halo – an aura of darkness representing evil.

The Sermon on the Mount Rather than talking about form, my usual interest in painting, I thought that this time I would focus on the symbolism of the content contained in an example of gothic art by focusing on a fresco of the Sermon on the Mount, once again by Fra Angelico (1395-1455). It is in cell 32 in the north wing of San Marco in Florence and was painted between 1440 and 1450. I should mention that I am indebted to a lecture given by Dr Lionel Gracey who was my colleague when I was teaching at the wonderful Maryvale Institute in Birmingham, England for much of the detailed information here.

First of all there is the symbolism of the colours of Jesus’s clothes. The red under garment or tunic is red, which is a symbol of blood and a sign of his humanity; while the blue outer garment or cloak symbolizes his divinity. I was told that originally in this fresco the blue of the cloak matched precisely the heavenly blue of the sky. Fra Angelico often uses this colour symbolism for Christ and it is seen in all three liturgical traditions (although it is certainly not true to say that depiction of Christ is limited to these colours). Shown below is the Last Supper of an earlier gothic master, Duccio; a modern icon of Christ by Gregory Kroug, the 20th century Russian émigré; and The Kiss of Judas by Caravaggio from the early 17th century. All have the same colour scheme for Christ's robes. Judas is depicted in Fra Angelico’s painting as well, indicated by the black halo – an aura of darkness representing evil.

Dr Gracey pointed out how unusually shod Jesus is, in a slipper of some sort rather than sandal or barefoot. He speculates that this is an allusion to the Eucharist because during Passover the Isrealites were required to be shod.

What strikes me about the composition of this fresco is the vertical dynamic in colour, light and composition that sweeps the eye up and down the painting through the geometric centre, which is somewhere around his knees. Our eyes sweep continually from earth to heaven and back, so to speak.

The colour dynamic comes in the match (when still bearing the original colours) between the blue shawl on Christ to the blue of the sky above. This causes our eyes to sweep upwards. Also, Christ’s hand points directly upwards. At this point commentaries often say that he is telling us figuratively that his kingdom is ‘not of this world’ (John 18:36). The light takes us down in the other direction. As described last week, the upper part of Christ is dark and the lower portion is light. The eye is taken from here to the brightly lit rock plateau beneath him.

A link is often made between the Sermon on the Mount and the 10 Commandments. Christ resumed these Commandments in the double precept of charity -- love of God and of the neighbour; He proclaimed them as binding in the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5). The mount upon which Jesus is preaching echoes Mt Sinai on which Moses was given the commandments. This parallel is emphasised by the bright illumination of the rock. Also Peter, whom Christ appears to be addressing, to his right, is ‘the rock’ upon whom He would build His Church.

Given Fra Angelico’s masterful manipulation of light (as I described last week, here) Dr Gracey suggested to me that this was the perfect painting for contemplation of the third Mystery of the Light in the Rosary, the Proclamation of the Gospel.

This is the third short article about Fra Angelico and the gothic that have been written for the New Liturgical Movement. The second was last week, already referred to and the first is archived here.

Fra Angelico's Theology of Light

I thought I would do a short series (I intend three at this stage) of articles focussing on paintings by the gothic artists, looking at two of my favourites Fra Angelico and Duccio. Fra Angelico, the 15th century Florentine artist is normally considered late gothic in style. Duccio, from Siena, worked earlier, in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. Duccio's work represents the more iconographic based style and Fra Angelic the more naturalistic. Looking at these two exemplars of early and late gothic art gives us a good sense of what characterises this tradition.

This is not just for the purpose of an art history discussion. I think that there is much to benefit from artists today who are trying to spark the ‘new epiphany of beauty’ by looking at the gothic tradition. First, it is one of the three authentic Catholic liturgical traditions cited by Pope Benedict XVI in The Spirit of the Liturgy. Also, I often find in conversation that his work appeals to people who have a similar understanding of the Faith, the liturgy and Catholic culture as I do. It seems that for many, Fra Angelico in particular has the balance of naturalism and idealism that nourishes the prayer of modern man. John Paul II gave him a special mention in his Letter to Artists. I think therefore that perhaps this could be a good starting point for artists to study and from which a distinctive art of Vatican II could develop in the future (just as the baroque, which developed from the base of the stylistic developments of the High Renaissance, might be considered the art of the counter-Reformation and of the Council of Trent). Only time will tell if I am right in this regard, of course.

I thought I would do a short series (I intend three at this stage) of articles focussing on paintings by the gothic artists, looking at two of my favourites Fra Angelico and Duccio. Fra Angelico, the 15th century Florentine artist is normally considered late gothic in style. Duccio, from Siena, worked earlier, in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. Duccio's work represents the more iconographic based style and Fra Angelic the more naturalistic. Looking at these two exemplars of early and late gothic art gives us a good sense of what characterises this tradition.

This is not just for the purpose of an art history discussion. I think that there is much to benefit from artists today who are trying to spark the ‘new epiphany of beauty’ by looking at the gothic tradition. First, it is one of the three authentic Catholic liturgical traditions cited by Pope Benedict XVI in The Spirit of the Liturgy. Also, I often find in conversation that his work appeals to people who have a similar understanding of the Faith, the liturgy and Catholic culture as I do. It seems that for many, Fra Angelico in particular has the balance of naturalism and idealism that nourishes the prayer of modern man. John Paul II gave him a special mention in his Letter to Artists. I think therefore that perhaps this could be a good starting point for artists to study and from which a distinctive art of Vatican II could develop in the future (just as the baroque, which developed from the base of the stylistic developments of the High Renaissance, might be considered the art of the counter-Reformation and of the Council of Trent). Only time will tell if I am right in this regard, of course.

The gothic style arose from a different understanding of man's perception of the natural world through his senses. The ideas that drove it developed from about 1000AD onwards with the rediscovery of the philosophy of Aritotle and the subsequent incorporation of his ideas into Christian thinking by figures such as St Thomas. The love of nature of Franciscan spirituality was also influential in popularizing the ideas. I have written more about this here.

As I wrote in a commentary on his Annunciation, Fra Angelico working late in the period is very interesting to study for his selective use of the features of the well observed naturalism such as perspective, shadow and figures in profile; and his retention at other times of those features of iconographic art.

If we look his Resurrection a fresco from one of the cells in the monastery of San Marco in Florence, we see Christ rising in an almond shaped mandorla, the traditional symbol of His glory, carrying the red and white Resurrection penant. The background is shadowy and dark and we see the tomb drawn with naturalistic perspective. The angel is in profile, which would never be seen in an iconographic painting, though shining with uncreated light which one would expect in iconographic art.

There is one stylistic feature that Fra Angelico uses that interests me greatly. This is his habit of putting the face of Christ in shadow. On first sight this is strange, since he shows the rest of the person of Christ shining with light and the face of the angel, a great, but nevertheless lesser being is totally in light. When I first noticed this I wondered why? A Dominican friar in England told me his interpretation of this: Fra Angelico is showing a light that is brighter still. In fact it is so bright that it blinds us - it is too much for us, fallen human beings who are observing Him, to bear. I find this explanation convincing, especially because we see in in other paintings by Fra Angelico, for example the Transfiguration and the Sermon on the Mount have the same feature.

Fra Angelico and the Gothic

When I first decided that I’d like to try to paint in the service of the Church I decided I wanted to paint like Fra Angelic (or perhaps Duccio). I suppose you might as well aim high! Fra Angelico, who worked in the 15th century, had the balance of naturalism and idealism that appealed to me. It seemed just right for prayer. It’s just an anecdotal observation, but when I meet people who have the same outlook in regard to the liturgy and orthodoxy in the Church, it seems that invariably they feel the same about him; and John Paul II described him in his Letter to Artists as one whose painting is ‘an eloquent example of aesthetic contemplation sublimated in faith’.

Unfortunately, the late-gothic style of Fra Angelico is not a living tradition and I couldn’t find anyone who painted that way who could teach me. I decided that as it appeared to sit stylistically between the Romanesque (which is an iconographic form) and the baroque and these were forms that are taught today, to some degree, I would learn both and try to work out how to combine the two. I am still working on that now!

When I first decided that I’d like to try to paint in the service of the Church I decided I wanted to paint like Fra Angelic (or perhaps Duccio). I suppose you might as well aim high! Fra Angelico, who worked in the 15th century, had the balance of naturalism and idealism that appealed to me. It seemed just right for prayer. It’s just an anecdotal observation, but when I meet people who have the same outlook in regard to the liturgy and orthodoxy in the Church, it seems that invariably they feel the same about him; and John Paul II described him in his Letter to Artists as one whose painting is ‘an eloquent example of aesthetic contemplation sublimated in faith’.

Unfortunately, the late-gothic style of Fra Angelico is not a living tradition and I couldn’t find anyone who painted that way who could teach me. I decided that as it appeared to sit stylistically between the Romanesque (which is an iconographic form) and the baroque and these were forms that are taught today, to some degree, I would learn both and try to work out how to combine the two. I am still working on that now!

What is it that characterizes gothic figurative art? We start to see a change in figurative art around 1200AD. The departure from the iconographic prototype occurred due to a different sense of the reliability of human experience. Information received through the senses was seen much more as a possible means of the grasping of truth. Tied in with this is the belief that the world we live in, although fallen and imperfect, is nevertheless good, ordered and beautiful. So there may be evil and suffering in the world, and it may not be as good and beautiful as it ought to be, but it is nevertheless God’s creation and still good and beautiful.

This change caused both the rise of naturalism in art and the development of science fostered by the Church. I have read of two main reasons for this. One is the incorporation of the philosophy of re-discovered works of Aristotle (who trusted the senses more than his teacher, Plato) into Christian thinking, by figures such as Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas. This provided the intellectual basis for the development. Second is the spirituality of St Francis of Assisi. He loved nature as the work of God and as Franciscan ideas spread so did an enthusiasm for, and curiosity about, nature.

This change caused both the rise of naturalism in art and the development of science fostered by the Church. I have read of two main reasons for this. One is the incorporation of the philosophy of re-discovered works of Aristotle (who trusted the senses more than his teacher, Plato) into Christian thinking, by figures such as Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas. This provided the intellectual basis for the development. Second is the spirituality of St Francis of Assisi. He loved nature as the work of God and as Franciscan ideas spread so did an enthusiasm for, and curiosity about, nature.

Let’s look at a very famous fresco by Fra Angelico of the Annunciation on the walls of a cell at San Marco in Florence. He consciously employs some of the developments of the new naturalism: there is cast shadow, there is single-point perspective creating a sense of depth in the covered cloister; the archangel is in profile. But there are also stylistic aspects that we are accustomed to seeing in iconography: the figures are painted in the middle distance, the edges of each shape are all sharply defined and the colour is evenly applied (unlike the baroque which has selectively blurred or sharp edges and selective use of colour or monochrome, usually sepia, rendering).

If we examine the further, we can see that the light source that is casting shadow is from the left. If cast light were the only source, the face of the Archangel would be dark, yet it is bright. Fra Angelico is showing the face of the Archangel glowing with the uncreated light of holiness, which is what we are used to seeing in the Byzantine iconographic form.

I was giving a lecture once about this painting and a student asked me about the shadow. He pointed out that Our Lady is a saint, he could see that her face wasn’t in shadow and there was strong halo, representing he uncreated light coming from her. But also pointed out that there is a strong cast shadow on the wall behind her. Wouldn’t you expect her radiance to obliterate that, he asked? I agreed with him, you would. But I couldn’t say why Fra Anglelico had painted it like this. I speculated that perhaps it was due to the fact that there were two light sources from the left – the natural light and the uncreated light from the angel and that the combined intensity of light would cause the shadow against the wall. I had to admit even as I said it that my answer sounded contrived. Nevertheless, it did seem deliberate. Another Annunciation, shown below, has the same shadows.

He suggested an answer: Fra Angelico was a Dominican, and not a Franciscan. At this time the question of her Immaculate Conception had not been decided and the Dominicans did not accept the Immaculate Conception and were in dispute with the Franciscans over the issue. Perhaps Fra Angelico was making a theological point to the Franciscans, he suggested by dimming her light ever-so slightly. This was an ingenious suggestion, and I couldn’t say that it wasn’t what Fra Angelico had in mind. I certainly preferred it to my answer!

Later, someone in another class, a priest, gave the most convincing reason so far. Luke 1 tells us that the words of the angel Gabriel were:, “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you.”