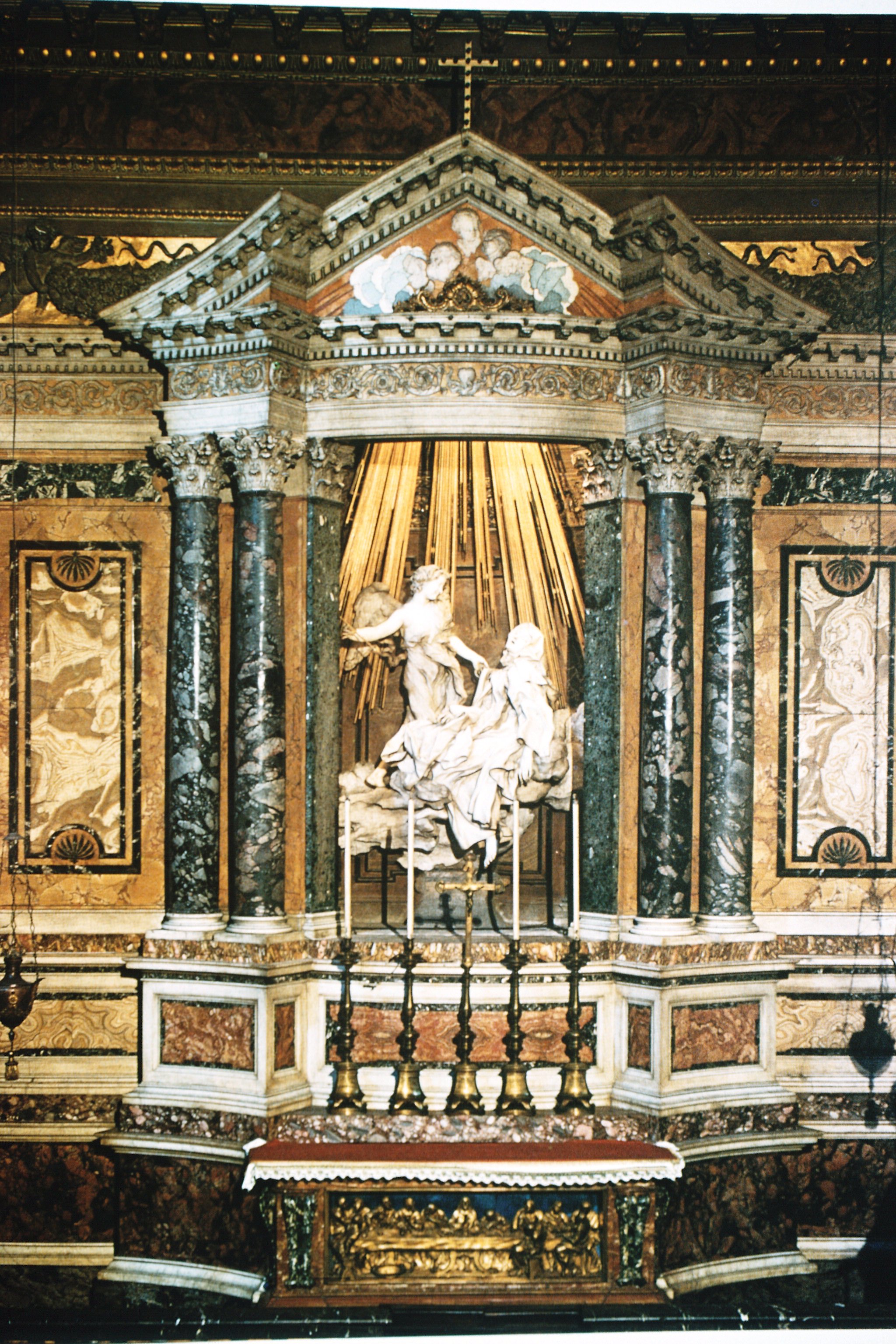

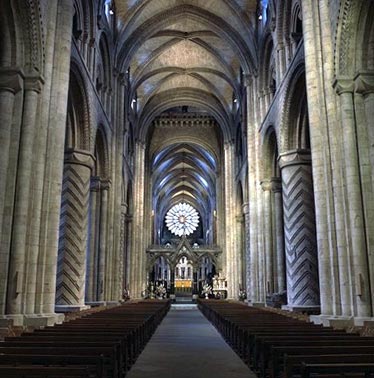

The first name that comes to mind when thinking of great sculptors is Bernini. When we look at his sculptures there are parallels to the baroque approach to painting. Although he is creating form in three dimensions, he still ‘paints’ in light and dark so that the baroque symbolism of the Light overcoming the darkness is there. He is quoted as having deliberately cut the lines in his statues deeper to accentuate his shadow, especially, as he said, that he did not have coloured paint to work with, only contrast of light and dark. This is why he took such care to consider that placement of his works relative to the source of light. Some artists, such as Alonso Cano and the other Spanish workers in wood of the baroque period did paint their work (hence the name ‘polychrome’ – many coloured). Unless the sculptor intends to follow Cano and paint his work then he must consider how the interplay of light and shadow in his work will affect the ability of the viewer to see what is intended.

One of the great problems that we see in modern attempts to create beautiful art is that it lacks power. The visual vocabulary of modern art has been developed to communicate what is bad. It cannot communicate goodness and truth well (ie beautifully) and retain its power, so if we try the result always seems to be sentimentality. We are all a product of our times, and will be influenced by the culture of the day whether we wish to be or not. This means the Christian artist must be especially aware of this tendency to sentimentality in his work.

The first name that comes to mind when thinking of great sculptors is Bernini. When we look at his sculptures there are parallels to the baroque approach to painting. Although he is creating form in three dimensions, he still ‘paints’ in light and dark so that the baroque symbolism of the Light overcoming the darkness is there. He is quoted as having deliberately cut the lines in his statues deeper to accentuate his shadow, especially, as he said, that he did not have coloured paint to work with, only contrast of light and dark. This is why he took such care to consider that placement of his works relative to the source of light. Some artists, such as Alonso Cano and the other Spanish workers in wood of the baroque period did paint their work (hence the name ‘polychrome’ – many coloured). Unless the sculptor intends to follow Cano and paint his work then he must consider how the interplay of light and shadow in his work will affect the ability of the viewer to see what is intended.

One of the great problems that we see in modern attempts to create beautiful art is that it lacks power. The visual vocabulary of modern art has been developed to communicate what is bad. It cannot communicate goodness and truth well (ie beautifully) and retain its power, so if we try the result always seems to be sentimentality. We are all a product of our times, and will be influenced by the culture of the day whether we wish to be or not. This means the Christian artist must be especially aware of this tendency to sentimentality in his work.

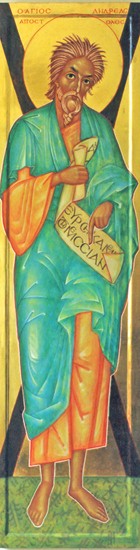

When I was learning to paint icons, my teacher Aidan Hart, told me to break curves up into a series of straight lines in order as a way of avoiding sentimentality and giving the painting rhythm and power. Later, when I was studying Western naturalism in Florence, part of my study involved drawing casts of Bernini statues. I saw that he had done something similar. The lines of drapery are usually represented not as curves, but as a series of intersecting lines (or perhaps more accurately, as series of broader arcs). It might be surprising to some that there are such parallels between iconography and the baroque, but I discovered a number which I recognised because of my exposure to both traditions. This common ground helped to reinforce the common threads of Christian art and to distinguish the naturalism of the 19th century from the baroque of the 17th century. It is why I would always say that even those artists who wish to specialize in the baroque style would benefit from learning iconography to a foundational level as well; or at the least from a study so that those stylistic features are better understood. We live in a different atmosphere from the 17th century and a clearer, more conscious recognition of what consitutes Christian culture is probably more important now than it was then, when just to be alive would have enabled people to soak up the essence of Christian culture without even thinking about it.

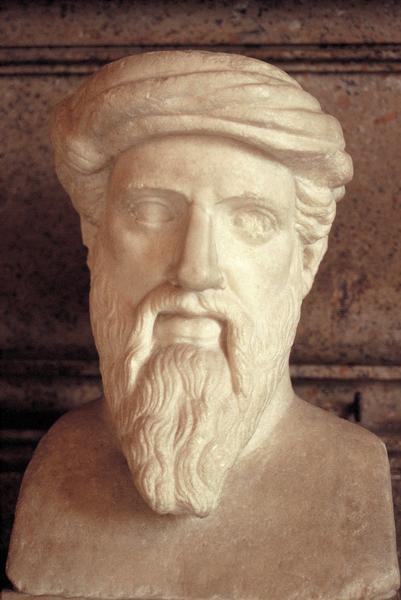

The other thing that is of interest is in connection with the training and working methods of artists at that time. Bernini is known today for his dazzling technique, but at the time, his genius was considered to be the ideas and vision that he had rather than in the skill in realizing it. There were other great sculptors whose style was similar and had great skill, for example Algardi and Finelli (in fact it is his sculpture of Cardinal Scipione Borghese shown above and not Bernini's, which is right).

The other thing that is of interest is in connection with the training and working methods of artists at that time. Bernini is known today for his dazzling technique, but at the time, his genius was considered to be the ideas and vision that he had rather than in the skill in realizing it. There were other great sculptors whose style was similar and had great skill, for example Algardi and Finelli (in fact it is his sculpture of Cardinal Scipione Borghese shown above and not Bernini's, which is right).

One of my teachers in Florence, and American called Matt Collins who still lives in Italy, wrote to me about this recently. I thought I would pass on part of the correspondence, which I found interesting and surprising. He described how Bernini ran a workshop and that for a while Bernini was not the greatest technician even in his own bodega.

'Today we appreciate Bernini for his fantastic technique. However he was not the most virtuoso marble sculptor of his time. Giuliano Finelli was. Bernini employed highly skilled assistants to help realize his ideas. His 'Genius' or 'Divine gift' as it was referred to in his time was his artistic sensibility and vision. The production of art in the 17th century was a collaborative process, not the misunderstood individual against society of today. Students of the of the past were not studying but working. Art education was in fact 'on the job' training. All the assistants received the same technical training. Art evolved from it constant practice. There was always work for a competent artist, so he could risk and push himself.

'Finelli's first biographer was a man called Giambattista Passeri. He may have known personally the sculptor. Finelli was born in Carrara in 1601. The first documentation about him is from 1616 about his relation to a Michelangelo Naccherino, a sculptor based in Naples. Naccherino moved around a lot, working in Rome and even Florence. Eventually, Finelli moved to Rome around 1620 and worked in Bernini's workshop. One of the most shocking revelations is that Finelli completed a lot of the detail work on Bernini's marbles. The virtuoso leaves on Bernini's Apollo and Daphne were most likely done by Finelli. Today, we attach 'Genius' to technique. Recent revelations about 17th century art production show that virtuoso technique was only a component of great art, not the sole determiner of 'Genius.' In fact, if you look at Finelli's independent work it is not very impressive outside of the technical realm.

'Passeri is quoted as saying: "vedendo la diligenza di Giuliano si valse di lui nelle due statue di Dafne, e di Apollo, che sono nella Villa Borghese a Porta Pinciana, nelle quali oltre il buon gusto, e disegno si vede un maneggio di marmo che pare impossible, che sia opera umana, e da essa Gian Lorenzo guadagno un nome immortale."

'It is roughly translated as: "recognizing Giuliano's capability, he(Bernini) utilized him in the production of the statues Apollo and Dafne that are in the Villa Borghese at Porta Pinciana. Apart from the good taste and competent design, one sees a treatment of marble that seems impossible, let alone a work by human hands. And it is from this that Gian Lorenzo(Bernini) name became immortal."After collaborating on many projects with little compensation Finelli left Bernini's workshop in 1629.'

Matt knows more than anyone else I know about the training methods and technique of the baroque and the High Renaissance and he has taught me a great deal over the years. He has just started his own blog which publicises his own work and discusses a lot of these technical aspects in an engaging way. Those interested should look here.

This article first appeared in July 2015.

Above, Bernini's (or perhaps Finelli's!) Daphne and Apollo

Cardinal Montalto by Finelli

Detail of Bernini's Ecstasy of St Theresa of Avila, shown in full below