And Art for Art’s Sake is Anti-Human

The purpose of art and the role of beauty in the culture have been subjects of ongoing debate. While some view art as existing purely for its own sake - ‘art for art’s sake’ - divorced from any broader utility or message, others argue that art must serve a didactic or ideological function. The traditional Christian perspective, however, offers a distinct understanding that avoids these extremes, and the result is art for God's sake, which, if done well, will always be art for our sake too.

The interior of St Mark's Cathedral Venice: Is this art for art's sake, or art for God's sake?

(Rob Hurson, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Central to the Christian view is recognising the profound unity of the material and spiritual dimensions in the human person. As beings composed of both body and soul, humans possess material and spiritual needs. Consequently, the purpose of art cannot be reduced solely to aesthetic considerations or purely practical or ideological aims. Rather, true art must harmonise these aspects, reflecting and serving the totality of human nature, material and spiritual.

This understanding is rooted in Christian anthropology, which sees beauty not as a superfluous addition to an object's utility but as an integral part of its purpose. When an object is truly beautiful, its beauty is seen as a sign that its purpose is in accord with God's governance of the world—a reflection of divine inspiration or the beauty of Creation itself.

Take, for example, something as mundane as a toothbrush. While its primary purpose is the practical one of cleaning teeth and promoting bodily health, a well-designed toothbrush incorporates elements of beauty that speak to a broader understanding of human well-being. Its harmonious design serves its practical function and invites the user to consider the more profound implications of oral hygiene for overall health and spiritual vitality. While few will consciously contemplate such things when brushing their teeth (least of all first thing in the morning or last thing at night!), most of us, even with something as simple as a toothbrush, would not choose an ugly one in preference to a beautiful one, given the choice. This means that they are accepting the invitation of beauty at some level.

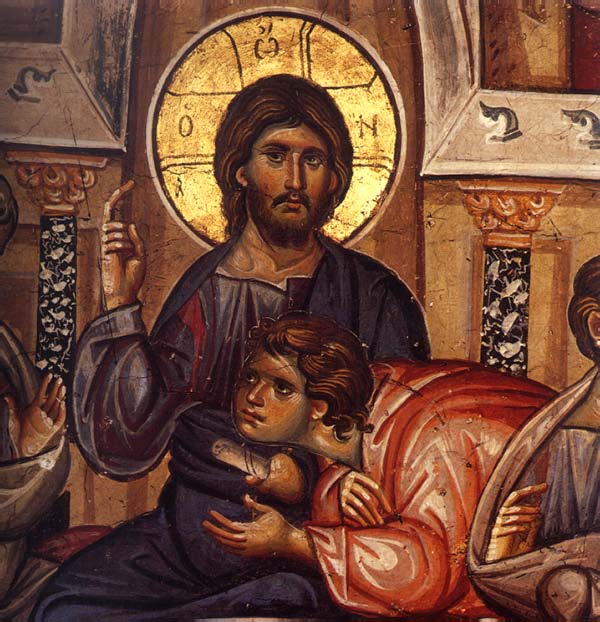

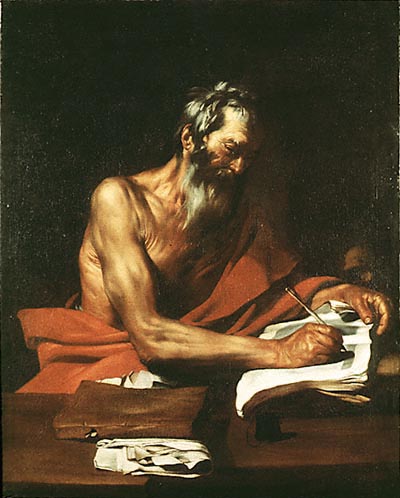

This principle is even more evident and more important in works of art with a direct spiritual or liturgical purpose, such as sacred art or architecture. In these cases, beauty plays a crucial role in elevating the human spirit and facilitating the contemplation of the divine. For instance, the beauty of a cathedral is not merely an aesthetic embellishment but a vital component of its purpose as a house of worship, drawing the hearts and minds of the faithful towards heaven.

The Christian perspective recognises that individuals possess free will and can respond positively or negatively to the call of beauty. While beauty can inspire a deepening desire for virtue and a closer relationship with God, it can also be rejected or dismissed as mere sentimentality.

Ultimately, the traditional Christian view sees art and beauty not as ends in themselves but as means of elevating the human person and facilitating a deeper engagement with the spiritual realm. Beauty is not a superficial adornment but a reflection of the divine order – a sign that an object or work of art fulfils its intended purpose in harmony with God's design.

In this understanding, the apprehension of beauty is not merely an emotional response but a profound experience that can engage the intellect, will, and emotions in a multifaceted way. It is a call to contemplate the divine, to pursue virtue, and to recognise the unity of the material and spiritual dimensions of human existence.

By integrating these perspectives, the traditional Christian view offers a nuanced and holistic approach to the purpose of art and the role of beauty – one that recognises their intrinsic value while situating them within a broader framework of human flourishing and spiritual growth..

One presumes that even Our Lady cleaned her teeth, and if she had done so, even this humble activity would have been done gracefully and beautifully.

I wrote this article in response to some comments and criticism of works of art made by readers on another blog after my earlier article on the work of the Spanish artist Kiko; many of my remarks about the tone of the commentators does not apply to thewayofbeauty.org readers, who are always generous in spirit even when being critical. However, I thought that some of the points about the basis of criticism might be of interest to you, so I reproduce it here...

I wrote this article in response to some comments and criticism of works of art made by readers on another blog after my earlier article on the work of the Spanish artist Kiko; many of my remarks about the tone of the commentators does not apply to thewayofbeauty.org readers, who are always generous in spirit even when being critical. However, I thought that some of the points about the basis of criticism might be of interest to you, so I reproduce it here...