Here is another piece by philosopher and member of the faculty of Pontifex University, Dr Carrie Gress. This first appeared on the university blog, blog.pontifex.university. Carrie's personal website is carriegress.com.

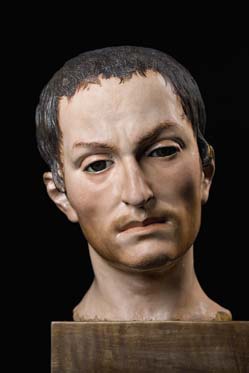

She is interviewing the sculptor Thomas Marsh who lives in Virginia. I think that the quality of his work speaks for itself. One comment I would make is that he percieves the difference between sacred art and portraiture, judging from the face of Our Lady which is shown in the photographs presented here. In sacred art the object is to portray the general characteristics of the saint's humanity. This is done through the particular, so we must see a unique person, but those unique characteristics are not emphasized as much as in portraiture - where the whole point is to emphasize what makes the subject different from everyone else. The result is a more idealized image, and this is what we see in the facial feature of Our Lady, which seem to draw on the Greek ideal for inspiration.

Here is another piece by philosopher and member of the faculty of Pontifex University, Dr Carrie Gress. This first appeared on the university blog, blog.pontifex.university. Carrie's personal website is carriegress.com.

She is interviewing the sculptor Thomas Marsh who lives in Virginia. I think that the quality of his work speaks for itself. One comment I would make is that he percieves the difference between sacred art and portraiture, judging from the face of Our Lady which is shown in the photographs presented here. In sacred art the object is to portray the general characteristics of the saint's humanity. This is done through the particular, so we must see a unique person, but those unique characteristics are not emphasized as much as in portraiture - where the whole point is to emphasize what makes the subject different from everyone else. The result is a more idealized image, and this is what we see in the facial feature of Our Lady, which seem to draw on the Greek ideal for inspiration.

Carrie writes:

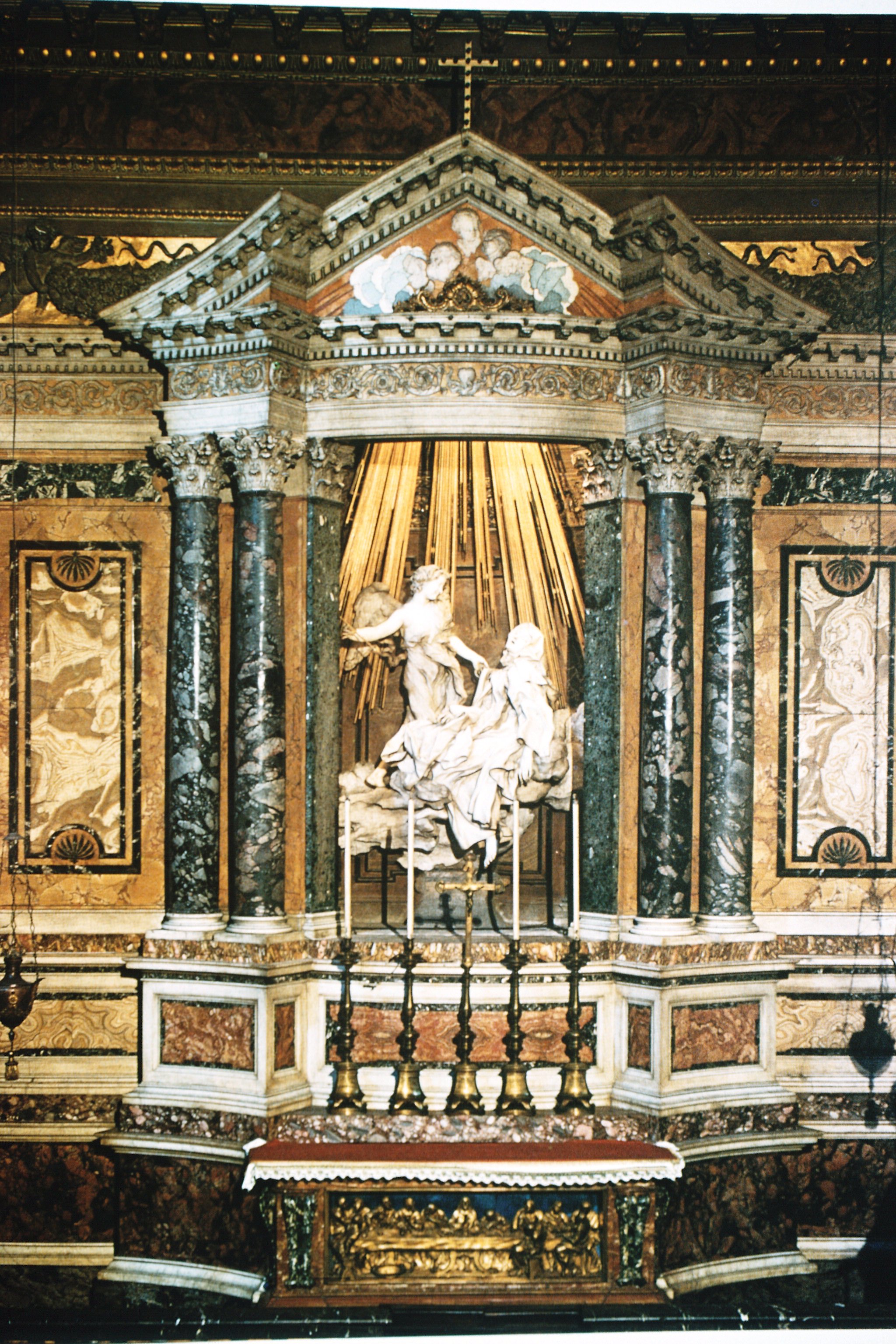

For sculptor and painter Thomas Marsh sacred art doesn’t need to fall into the trap of religious kitsch or modernist fads. From Santa Cruz to Washington, D.C., Marsh’s work can be seen in churches, monasteries, monuments and memorials.

Trained in the realist school of painting and sculpture, Marsh works to capture something unique about the human spirit that conjures up something deeper in the soul than novelty or saccharine sentimentality. Through his work of both the sacred and secular, Marsh is trying to capture a type of contemplation akin to prayer.

I spoke with Marsh about his realist training and its evangelizing potential.

Gress: You are a sculptor, specializing in sacred art. What led you to this vocation?

Marsh: My love of sculpting the figure goes back to childhood, at about age 8, when I borrowed some plastilina clay from my sister who was a college art student at the time. I made a number of character studies simply because it was fascinating.

I didn’t consciously focus on being a sculptor as my vocation until I was 18 and had just enrolled as an architecture student at Iowa State University. I took as many art classes as ISU had to offer taken mostly through the Architecture Department which, fortunately, had not abandoned classical principles of training in realism in their drawing classes.

I then transferred to a small, private, heavily endowed art school in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the Layton School of Art, and earned a Bachelors of Fine Arts in Painting in 1974. As was the case with the Architecture Department at ISU, the Painting Department at Layton maintained a high degree of classical training, where the Sculpture Department did not. However, I was blessed to be given the use of a professional sculpture studio (the sculptor had recently passed away) so at ages 21-23 I had a marvelous, private, professional studio for my sculpture work.

From 1974-77 I studied sculpture at California State University, Long Beach, where I received my Masters in Fine Arts in sculpture. Through my graduate professors I had direct artistic genealogical links to Ivan Mestrovic and Rodin. After receiving my MFA, I became the apprentice to the modern figurative master Milton Hebald for a year in Italy. The time spent in Italy, many trips since, has been deeply formative of my love for great Christian art.

Gress: How did you go about following your passion for art and the beautiful?

Marsh: “Art” and “the beautiful” are not synonymous, since one is human action producing a creative structure with aesthetic attributes, for the perceiver’s aesthetic experience; and the other, the concept of “beauty” or “the beautiful” is a principle, a universal in the world of the spirit, which is no less real than the material.

My passions for each are inextricably intertwined. From that early childhood love of sculpting the figure, my passion for beauty in art evolved as my level of aesthetic understanding grew.

Looking back, it felt more as if my passion had been “drawn out” or “pulled out” by the great universal principles of art, such as, form, representation, complexity, emotional intensity, and beauty… rather than my having “followed my passion.”

Gress: Do you consider your work to be evangelical?

Marsh: Yes, I pray to God that my work is evangelical! In 1987, I gave a public lecture at the University of San Francisco titled “Figurative Art and the Human Spirit.” In it, I outlined my theory that the era of modernism in art was dying or even effectively dead. History has to a large extent, borne out that prediction.

My reasoning was and is as follows: expression theory is the intellectual foundation of modernism. Put simply, that means that the idea or concept of the work of art, its “expression,” is more significant than the attributes of the work of art itself. In order to aesthetically evaluate works of art based on their ideas alone, there is no fundamental criterion for aesthetic value, except “the new.” Hence, we witnessed the ever faster spiraling of art movements for most of a century. But this spiral eventually negated itself, when the “new” became tedious: it was no longer shocking or novel or exciting.

I predicted that a different, though not new, dominant role for art in human life would emerge: art as a vehicle for personal and social transformation. This transition from modernism based on expression theory to art as a vehicle for transformation is still in process, and is quite visible now. The mainstream art world, including major museums, serious galleries, and art critics in major publications, still holds fast to the modernist premise. But it’s clear that their citadel is crumbling, and that now the dominant role of art in human life is art as a vehicle for personal and social transformation.

Art in the service of evangelization is certainly transformative art! On a very particular level in visual art, my own work attempts to embody the work of art with forms that facilitate heightened awareness of our human spirit, or personhood. It is this experience of personhood that is the manifestation of the soul in human earthly life. My work is evangelical even beyond literal representations of Biblical figures because the human figure in art has the capacity to draw us into this experience, and such experience, as a parallel to prayer, has the power to draw us closer to God.

I also have done secular work all my life as a sculptor, painter, and drawer. Even secular work, such as the surfing monument in the Santa Cruz, California or the Victims of Communism Memorial in Washington, D.C., or (especially) portrait work, has the capacity to bring us closer to God.

Gress: What have been some of your recent projects?

Marsh: In 2013, I completed a St. Joseph, Patron of the Unborn figure for St. Vincent’s Hospital in Orange Park, Florida near Jacksonville. This is a small healing shrine, though the figure is life size, in the vestibule of the Chapel at the hospital. It is meant to facilitate the prayers for and about those women who have had abortions, or who have suffered miscarriages. It is patterned after a larger version of this same concept, installed on the grounds of the Oblates of St. Joseph in Santa Cruz, CA in 2001.

In 2014, I completed two castings of a work, St. Joseph, Protector of Preachers, one in bronze for the Priory of St. Thomas Aquinas Catholic Church in Charlottesville, Virginia, and one in gypsum cement casting for the interior entrance to the church. This work has a narrative dimension, and at the same time facilitates our human spirit experience through the stylistic character of my figures. St. Joseph, and a dog – these are the Dominicans!

I am poised to begin a major work: a Marian Rosary Prayer Walk which integrates a larger than life figure of Mary and a 75’ long landscaped rosary prayer walk.

Gress: Your work, particularly when it comes to Christ and the angels, offers a very lifelike representation emphasizing their strength and masculinity. Is this intentional?

Marsh: This approach emphasizing the masculine strength of Christ and the archangels Gabriel and Michael, and also St. John, all at St. Mary Catholic Church in Fredericksburg, Virginia, is very deliberate! I have also tried to bring this approach to the figures of St. Joseph, Patron of the Unborn, in Santa Cruz, California and in Jacksonville, Florida; the figure of John the Baptist at Mission San Juan Bautista, California; and the figure of Christ on the cross at St. Joachim Catholic Church in Madera, California.

I’m a realist sculptor who strives to create original and meaningful work in the genre of ecclesiastical and liturgical sculpture. Unfortunately, much of the sculpture in today's Catholic art world is filled with clichés and copies (just pick up any religious art catalogue), not to mention mediocre sculpting. I feel strongly that the fortis et suavis (strong and gentle) character of Joseph, and Christ, should be the model for male figures, and for the overwhelming/terrifying/awe-striking figures of archangels. In today’s social and political context, where the natural complementarity of the sexes is being questioned, I feel is it critical to imply the God-created natural law basis of the male side of human male-female complementarity.

http://thomasmarshsculptor.net/images/grandfather%20pruitt2.jpg

Here is another piece by philosopher and member of the faculty of Pontifex University, Dr Carrie Gress. This first appeared on the university blog,

Here is another piece by philosopher and member of the faculty of Pontifex University, Dr Carrie Gress. This first appeared on the university blog,

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

The tradition of the Eastern Church

The tradition of the Eastern Church