A transformative journey that combines traditional Catholic spirituality with holistic artistic formation and is offered to everyone. Become the creative you were meant to be. Designed by David Clayton, Artist-in-Residence at the Scala Foundation and Provost, Pontifex University

Graced Imagination: Recovering True Creativity in the Age of Authenticity

Modern art and architecture reject traditional harmony and form, intentionally breaking with the past and seemingly deliberately disregarding beauty. This revolution in art is a sign of an even more profound revolution in the understanding of the human person and the desire to change Western civilization radically.

The Traditional Formation of the Artist is Mystagogical Catechesis and a Formation for the New Evangelisation

The fruits of a traditional artistic training in the formation of the person are such, I would say, that it would be useful too (with minimal adaption) for anybody, regardless of his personal vocation. And so would be of interest not just to artists, but to all people; (and especially those who are interested in the formation of children). It is a training in the via pulchritudinis and is the formation of the New Evangelisation, I suggest.

Beauty and Creativity in Scientific Research

The Spirituality of Artistic Creativity - Find Your Personal Pilgrimage

Keep the Dates! Scala Foundation Conference, April 21-22, 2023. Princeton, NJ,

Featuring Aidan Hart, Jonathan Pageau and David Clayton

Scala Foundation will host its next conference on April 21-22, 2023 on the campus of Princeton Theological Seminary. The Scala Foundation’s mission is to restore meaning and purpose to American culture through beauty, liberal arts education and religion. The name Scala comes from the Latin word for a ladder. With God’s help we can ascend the the ladder of perfection, like the angels in Jacob’s dream.

This conference, entitled Art, the Sacred, and the Common Good: Renewing Culture through Beauty, Education and Worship. brings together Christians from different denominations with a view to us all working together to evangelize American culture as one of beauty that speaks of the Beauty of God. It will feature a dozen total speakers, including the best-selling author Andy Crouch and the internationally renowned artists Jonathan Pageau and Aidan Hart. I am honored to have been asked to moderate a conversation with my friends Jonathan and Aidan on the renewal of sacred art. We are particularly blessed to have Aidan, my former teacher, coming from England especially for the conference.

In the afernoon session, Elizabeth Black, Principal of St Stephen’s K-9 school in Grand Rapids, MI, will talk about how she has implemented The Way of Beauty into her school. I visited her school this past summer and wrote about it, here.

I was at the 2022 conference as both speaker and attendee and it was one of the most hopeful, constructive and inspiring events of this type that I have attended.

Scala Foundation’s Executive Director, Margarita Mooney Clayton writes:

The goal is to show how traditions in beauty, education and worship, although under threat, are indeed being renewed. Attendees at this event will have the opportunity to:

Meet internationally renowned artists and prestigious scholars;

Experience beautiful sacred music, art, and architecture;

Learn why beauty is essential to personal happiness and civic participation;

Be inspired by educators who form virtues through beauty;

Build community with people pursuing the way of beauty.

One attendee last year said:

“The conference was rejuvenating. Inspiring. Encouraging. Enlivening. As an architecture major who went into youth ministry and now doing graduate work in theology, this conference allowed me to connect the dots between art, faith and service.”

The conference begins with a dinner and keynote lecture on Friday night, followed by a full day on Saturday of keynote addresses, panels, and breakout sessions with speakers. Attendees will also have the chance to participate in chorale prayer for liturgy of the hours, to see an exhibit of archives of sacred texts from Princeton Theological Seminary, and see the art of the speakers and other local artists.

Registration will begin in December 2022. Visit the conference website to let them know you are interested and they will send you advance notice of registration!

I encourage all to attend!

Discerning My Vocation as an Artist

How I came to be doing what I always dreamed of

How I came to be doing what I always dreamed of

Following on from the last piece, as mentioned I am reposting an article first posted about four years ago. In connection with that, it is worth mentioning that one's personal vocation can change as we grow older. I am not necessarily set in the same career or life situation for life. What was fulfilling for me as a young man may not be right for me now. So I do think that regular reassessment is something that should be considered.

I wrote this originally because people regularly ask me how they can become an artists. One response to this is to describe the training I would recommend for those who are in a position to go out and get it. You can read a detailed account of this in the online course now available. However, this is only part of it (even if you accept my ideas and are in a position to pay for the training I recommend). It was more important for me first to discern what God wants me to do. I did not decide to become an artist until I was in my late twenties (I am now 52). That I have been able to do so is, I believe, down to inspired guidance. I was shown first how to discern my vocation; and second how to follow it. I am not an expert in vocational guidance, so I am simply offering my experience here for others to make use of as they like.......

I am a Catholic convert (which is another story) but influential in my conversation was an older gentleman called David Birtwistle, who was a Catholic. (He died more than ten years ago now.) One day he asked me if I was happy in my work. I told him that I could be happier, but I wasn’t sure what else to do. He offered to help me find a fulfilling role in life.

He asked me a question: ‘If you inherited so much money that you never again had to work for the money, what activity would you choose to do, nine to five, five days a week?’ One thing that he said he was certain about was that God wanted me to be happy. Provided that what I wanted to do wasn’t inherently bad (such as drug dealing!) then there was every reason to suppose that my answer to this question was what God wanted me to do.

While I thought this over, he made a couple of points. First, he was not asking me what job I wanted to do, or what career I wanted to follow. Even if no one else is in the world is employed to do what you choose, he said, if it is what God wants for you there will be way that you will be able to support yourself. He told me to put all worries about how I would achieve this out of my mind for the moment. Such doubts might stop me from having the courage to articulate my true goal for fear of failure. Remember, he said, that if God’s wants you to be Prime Minister, it requires less than the ‘flick of His little finger’ to make it happen. If wanted to do more than one thing, he said I should just list them all, prioritise them and then aim first for the activity at the top of the list.

I was able to answer his question easily. I wanted to be an artist. As soon as I said it, I partly regretted it because the doubts that David warned me about came flooding in. Wasn’t I just setting myself up for a fall? I had already been to university and studied science to post-graduate level. How was I ever going to fund myself through art school? And even if I managed that, such a small proportion of people coming out of art school make a living from art. What hope did I have? I worried that I would end up in my mid-thirties a failed artist with no other prospects. David reassured me that this was not what would happen. This process did not involve ever being reckless or foolish, but I would always need faith to stave off fear.

I was able to answer his question easily. I wanted to be an artist. As soon as I said it, I partly regretted it because the doubts that David warned me about came flooding in. Wasn’t I just setting myself up for a fall? I had already been to university and studied science to post-graduate level. How was I ever going to fund myself through art school? And even if I managed that, such a small proportion of people coming out of art school make a living from art. What hope did I have? I worried that I would end up in my mid-thirties a failed artist with no other prospects. David reassured me that this was not what would happen. This process did not involve ever being reckless or foolish, but I would always need faith to stave off fear.

Next David suggested that I write down a detailed description of my ideal. He stressed the importance of crystallizing this vision in my mind sufficient to be able to write it down. This would help to ensure that I spotted opportunities when they were presented to me. Then, always keeping my sights on the final destination, I should plan only to take the first step. Only after I have taken the first step should I even think about the second. Again David reiterated that at no stage should I do anything so reckless that it may cause me to let down dependants, to be unable to pay the rent or put food on the table.

The first step, he explained, can be anything that takes me nearer to my final destination. If I wasn’t sure what to do, he told me to go and talk to working artists and to ask for their suggestions. There are usually two approaches to this: either you learn the skills and then work out how to get paid for them; or even if you have to do something other than what you want, you put yourself in the environment where people are doing it. For example, he suggested that I might get a job in an art school as an administrator. My first step turned out to be straighforward. All the artists I spoke to told me to start by enrolling for an evening class in life drawing at the local art school.

My experience since has been that I have always had enough momentum to encourage me to keep going. To illustrate, here’s what happened in that first period: the art teacher at Chelsea Art School evening class noticed that I liked to draw and suggested that I learn to paint with egg tempera. I tried to master it but struggled and after the class was finished I told someone about this. He happened to know someone else who, he thought, worked with egg tempera. He gave me the name and I wrote asking for help. About a month later I received a letter from someone else altogether. It turned out that the person I had written to was not an artist at all, but had been passed the letter on to someone who was called Aidan Hart. Aidan was an icon painter. It was Aidan who wrote to me and who invited me to come and spend the weekend with him to learn the basics. Up until this point I had never seen or even heard of icons. Aidan eventually became my teacher and advisor.

There have been many chance meetings similar to this since. And over the course of years my ideas about what I wanted to do became more detailed or changed. Each time I modified the vision statement accordingly, and then looked out for a new next step – when I realized that there was no school to teach Catholics their own traditions, I decided that I would have to found that school myself and then enlist as its first student. Later it dawned on me that the easiest way to do thatwas to learn the skills myself from different people and then be the teacher.

There have been many chance meetings similar to this since. And over the course of years my ideas about what I wanted to do became more detailed or changed. Each time I modified the vision statement accordingly, and then looked out for a new next step – when I realized that there was no school to teach Catholics their own traditions, I decided that I would have to found that school myself and then enlist as its first student. Later it dawned on me that the easiest way to do thatwas to learn the skills myself from different people and then be the teacher.

I was also told that there were two reasons why I wouldn’t achieve my dream: first, was that I didn’t try; the second was that en route I would find myself doing something even better, perhaps something that wasn’t on my list now. When this happens you will be enjoying so much you stop looking further.

David also stressed how important it was always to be grateful for what I have today. He said that unless I could cultivate gratitude for the gifts that God is giving me today, then I would be in a permanent state of dissatisfaction. In which case, even if I got what I wanted I wouldn't be happy. This gratitude should start right now, he said, with the life you have today. Aside from living the sacramental life, he told me to write a daily list of things to be grateful for and to thank God daily for them. Even if things weren’t going my way there were always things to be grateful for, and I should develop the habit of looking for them and giving praise to God for his gifts. He also stressed strongly that I should constantly look to help others along their way.

As time progressed I met others who seemed to be understand these things. So just in case I was being foolish I asked for their thoughts. First was an Oratorian priest. He asked me for my reasons for wanting to be an artist. He listened to my response and then said that he thought that God was calling me to be an artist. Some years later, I asked a monk who was an icon painter. He asked me the same questions as the Oratorian and then gave the same answer.

What was interesting about all three people so far is that none of them asked what seemed to be the obvious question: ‘Are you any good at painting?’ I asked the monk/artist why and he said that you can always learn the skills to paint, but in order to be really good at what you do you have to love it.

Some years later still, when I was studying in Florence, I went to see a priest there who was an expert in Renaissance art. It was for his knowledge of art that I wanted to speak to him, rather than spiritual direction. I wanted to know if my ideas regarding the principles for an art school were sound. He listened and like the others encouraged me in what I was doing. Three years later, after yet another chance meeting, I was offered the chance to come to Thomas More College of Liberal Arts in New Hampshire, to do what precisely what I had described to the priest in Florence.

In my meeting with him the Florentine priest remarked in passing, even though I hadn’t asked him this, that he thought that it was my vocation to try to establish this school. He then said something else that I found interesting. He warned me that I couldn’t be sure that I would ever get this school off the ground but he was certain that I should try. As I did so, my activities along the way would attract people to the Faith (most likely in ways unknown to me). This is, he said, is what a vocation is really about.

How Liturgy, Prayer and Intuition Are Connected - Recognition of Pattern and Order

Modern research into how firefighters and nurses respond to a crisis supports the idea that a traditional education in beauty will develop our powers of intuitive decision making.

In a great series of recorded lectures entitled The Art of Critical Decision Making, former Harvard business school professor and current Trustee Professor of Management at Bryant University, Michael A Roberto discusses the importance of intuition in making decisions; and the factors that influence the reliability of our intuitive faculty. He illustrates his points with some striking real-life stories of people relying upon or ignoring intuition (sometimes with dire consequences); and backs up what he says with modern psychological research.

Modern research into how firefighters and nurses respond to a crisis supports the idea that a traditional education in beauty will develop our powers of intuitive decision making.

In a great series of recorded lectures entitled The Art of Critical Decision Making, former Harvard business school professor and current Trustee Professor of Management at Bryant University, Michael A Roberto discusses the importance of intuition in making decisions; and the factors that influence the reliability of our intuitive faculty. He illustrates his points with some striking real-life stories of people relying upon or ignoring intuition (sometimes with dire consequences); and backs up what he says with modern psychological research.

For example, he tells of a number of occasions when nurses in cardiac intensive care units predict that a patient is going to have a heart attack. This is despite the fact that the specialist doctors could see no problem and the standard ways of monitoring the patients' condition indicated nothing wrong either. When such nurses are asked why they think the situation is bad, they cannot answer. As a result their predictions were disregarded. As it turned out, very often and sadly for the people involved, the nurses were right. In order to protect patients in future people started to ask questions and do research on why the nurses could tell there was a problem. What was it they were reacting to, even if they couldn't say initially?

The most dramatic tale he related was of a crack team of firefighters who were specialists in dealing with forest and brush fires and would be helicoptered into any location within a large part of the West to deal with fires when they broke out. The leader of the group was respected firefighter who was a taciturn individual who lead by example. He was not a good natural communicator, but usually this did not matter. One day they responded to a call and went to a remote site in California. When they assessed the situation they discerned the pace of spread of the fire, the direction it was going and so worked out how to deal with it safely. These judgments were important because if they got it wrong the brush fire could move faster than any man could run and they would be in trouble. Initially things went as expected but then suddenly the leader stopped and told everybody to do as he was doing. He threw a match to the ground and burnt an area in the grass of several square yards and then put it out. He then lay down on the burnt patch and waited. When asked why, except to say that he thought they were in danger he was unable to answer - he couldn't articulate clearly the nature of the danger or why this would action help. As a result even though he was respected, his advice was ignored by the team. Suddenly the fire turned and ran straight at them, in the panic the reaction of even these firefighters, was to run. This was the wrong thing to do, as the fire caught them and tragically they died. The only survivor was the leader. He was lying in the already burnt patch that was surrounded by brush fire as it swept through the area, but was itself untouched by the advancing blaze as there was no grass to burn within it. He just waited until the surrounding area burnt itself out and then walked away.

In both cases, the practitioners were experienced people who got it right, but weren't believed by others because people were not inclined to listen to the intuition of others if it couldn't be supported by what they thought was a reasonable explanation.

Dr Roberto describes how research since suggests that it is the level of experience in situ that develops an intuitive sense that is accurate enough to be relied upon. What experience teaches is the ability to spot patterns of events. Through repeated observation they know that when certain events happen, they are usually related to others and in a particular way. Even in quite simple situations the different possible permutations of events would be quite complex to describe numerically and so scientific theorems may have difficulty predicting outcomes based upon them. However, the human mind is good at grasping the underlying pattern of any given situation at an intuitive level, and then can compare with what usually happens by consulting the storehouse of the memory of past events. In these situations described, of the fire and the cardiac unit, all the indicators usually referred to by the text books were within the range of what was considered safe. However, what the experienced nurse and firefighter spotted was a particular unusual combination that pointed to danger. This apprehension of truth was happening at some pre-conscious level and is not deduced step by step, hence their difficulties in articulating the detail of why they felt as they did.

While this ended in disaster at first, lessons were learnt. As a result of this, it was recognized that a good decision making processes ought to take into account at least, the intuition of experienced people. Prof Roberto described how hospitals and firefighters and others learning from them, have incorporated it into their critical decision making processes. This should be done with discernment - intuition is not infallible and the less experienced we are in a particular environment, the less reliable it is so this must be taken into account as well.

It also depends on the person. Some people develop that sense of intuition in particular situations faster than others because the intuitive faculty is more highly developed. This, in my opinion, is where the traditional education in beauty might help. In order to develop our sense of the beautiful, this education teaches us to recognize intuitively the natural patterns and interrelationships that exist in the cosmos. When we do so, we are more highly tuned to its beauty and if we were artists we could incorporate that into our work. For non-artistic pursuits we can still apply this principle of how things ought to be to make our activity beautiful and graceful. Also, we have a greater sense of the cause of lack of beauty, when something is missing and the pattern is incomplete or distorted. In these situations we can see how to rectify the situation. This is the part that would help the firefighter or nurse, I believe. The education I am describing will not replace the specialist experience that gave those nurses the edge, but by deeply impressing upon our souls the overall architecture of the natural order, it will develop the faculty to learn to spot the patterns in particular situations and allow them to develop their on-the-job intuition faster.

The greatest educator in beauty is the worship of God in the liturgy and especially when the liturgy of the hours harmonized with our worship of the Mass with the Eucharist at the center. When we pray well it should engage the whole person, body and soul, in such a way that we conform totally to that cosmic pattern. In our book, The Little Oratory, A Beginner's Guide to Prayer in the Home, I describe both the nature of that pattern and also how in the home we can even reinforce certain aspects of it in the formation of children. In God's plan that intuitive sense is developed to help us in ordering all our daily activities to his plan (which would include potentially firefighting and nursing and indeed most human activity). This development of intuition not only improves decisions made in a crisis, but also makes us more creative. I discuss the connection between intuition and creativity in a past article about creativity in science. Through this at work, in the home or in our worship, we can contribute to a more beautiful culture of living for everyone. This is the hoped for New Evangelization and John Paul II's 'new epiphany of beauty' that draws people to the Faith.

A Beautiful Pattern of Prayer - the Path to Heaven is a Triple Helix…

...And it passes through an octagonal portal.

...And it passes through an octagonal portal.

Liturgy, the formal worship of the Church - the Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours, the Eucharist at its centre - is the ‘source and summit of Christian life’. We are made by God to be united with him in heaven in a state of perfect and perpetual bliss, a perfect exchange of love. All the saints in heaven are experiencing this and liturgy is what they do. It is what we all are made to do; this how it is the summit of human existence. Our earthly liturgy is a supernatural step into the heavenly liturgy, this unchanging yet dynamic heavenly drama of love between God and the saints; and the node, the point at which all of the cosmos is in contact with the supernatural is Christ, present in the Eucharist. It is more fantastic than anything ever imagined in a sci-fi drama. There is no need to watch Dr Who to see a space-time vortex, when I take communion at Mass (assuming I am in the proper state of grace) I pass through one. And there’s no worry about hostile aliens, that battle is fought and won.

Everything else that the Church offers and that we do is meant to deepen and intensify our participation in this mystery. Through the participation in the liturgy, we pass from the temporal into a domain that is outside time and space. Heaven is a mode of existence where all time, past and future is compressed into single present moment; and all places are present at a single point.

Our participation in this cannot be perfect in this life, bound as we are by the constraints of time and space. We must leave the church building to attend to the everyday needs of life. However, this does not, in principle, mean that we cannot pray continuously. The liturgy is not just the summit of human existence; it is the source of grace by which we reach that summit. In conforming to the patterns and rhythms of the earthly liturgy in our prayer, we receive grace sufficient to sanctify and order all that we do, so that we are led onto the heavenly path and we lead a happy and joyous life. This is also the greatest source of inspiration and creativity we have. We will get thoughts and ideas to help us in choices that we make at every level and which permeate every action we take. Then our mundane lives will be the most productive and fulfilling they can be.

How do we know what these liturgical patterns are? We take our cue from nature, or from scripture. Creation bears the thumbprint of the Creator and through its beauty it directs our praise to God and opens us to His grace. The patterns and symmetry, grasped when we recognize its beauty, are a manifestation of the divine order.

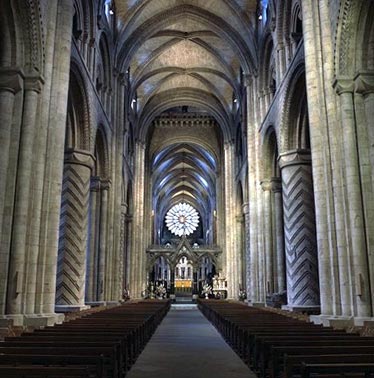

Traditional Christian cosmology is the study of the patterns and rhythms of the planets and the stars with the intention of ordering our work and praise to the work and praise of the saints in heaven. This heavenly praise is referred to as the heavenly liturgy. The liturgy that we participate, which is connected supernaturally to the heavenly liturgy is called the earthly liturgy. The liturgical year of the Church is based upon these natural cycles of the cosmos. By ordering our worship to the cosmos, we order it to heaven. The date of Easter, for example, is calculated according to the phases of the moon. The earthly liturgy, and for that matter all Christian prayer, cannot be understood without grasping its harmony with the heavenly dynamic and the cosmos. In order to help us grasp this idea that we are participating in something much bigger that what we see in the church when we go to Mass, the earthly liturgy should evoke a sense of the non-sensible aspect of the liturgy through its dignity and beauty and especially the beauty and solemnit of the art and music we use with it. All our activities within it: kneeling, praying, standing, should be in accordance with the heavenly standard; the architecture of the church building, and the art and music used should all point us to what lies beyond it and give us a real sense that we are praising God with all of his creation and with the saints and angels in heaven. When we pray in accordance with these patterns we are opening ourselves up to God’s helping hand at just the moment when it is offered. This is the prayer that places us in directly in beam of the heat lamp of God’s grace.

The harmony and symmetry of the heavenly order can be expressed numerically. For example, because of the seven days of creation in Genesis there are seven days in the week (corresponding also to a half phase of the idealised lunar cycle). The Sunday mass is the summit of the weekly cycle. In the weekly cycle there is in addition day, the so-called eighth ‘day’ of creation, which symbolises the new order ushered in by the incarnation, passion, death and resurrection of Christ. Sunday the day of his resurrection, is simultaneously the eighth and first day of the week (source and summit). Eight, expressed as ‘7 + 1’ is a strong governing factor in the Church’s earthly liturgy. (It is why baptismal fonts and baptistries are constructed in an octagonal shape and why you might have octagonal patterns on a sanctuary floors.)

The harmony and symmetry of the heavenly order can be expressed numerically. For example, because of the seven days of creation in Genesis there are seven days in the week (corresponding also to a half phase of the idealised lunar cycle). The Sunday mass is the summit of the weekly cycle. In the weekly cycle there is in addition day, the so-called eighth ‘day’ of creation, which symbolises the new order ushered in by the incarnation, passion, death and resurrection of Christ. Sunday the day of his resurrection, is simultaneously the eighth and first day of the week (source and summit). Eight, expressed as ‘7 + 1’ is a strong governing factor in the Church’s earthly liturgy. (It is why baptismal fonts and baptistries are constructed in an octagonal shape and why you might have octagonal patterns on a sanctuary floors.)

Without Christ, the passage of time could be represented by a self enclosed weekly cycle sitting in a plane. The eighth day represents a vector shift at 90° to the plane of the circle that operates in combination with the first day of the new week. The result can be thought of as a helix. For every seven steps in the horizontal plane, there is one in the vertical. It demonstrates in earthly terms that a new dimension is accessed through each cycle of our participation temporal liturgical seven-day week.

The 7+1 form operates in the daily cycle of prayer in the Divine Office too. Quoting Psalm 118, St Benedict incorporates into his monastic rule the seven daily Offices of Lauds, Prime, Tierce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline; plus an eighth, the night or early-morning Office, Matins.

The 7+1 form operates in the daily cycle of prayer in the Divine Office too. Quoting Psalm 118, St Benedict incorporates into his monastic rule the seven daily Offices of Lauds, Prime, Tierce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline; plus an eighth, the night or early-morning Office, Matins.

Prime has since been abolished in the Roman Rite, but usually the 7+1 repetition is maintained by having daily Mass (not common in St Benedict’s time). Eight appears in the liturgy also in the octaves, the eight-day observances, for example of Easter. Easter is the event that causes the equivalent vector shift, much magnified, in the annual cycle. The Easter Octave is eight solemnities – eight consecutive eighth days that starts with Easter Sunday and finishes the following Sunday.

These three helical paths run concurrently, the daily helix sitting on the broader weekly helix which sits on the yet broader annual helix. We are riding on a roller coaster triple corkscrewing its way to heaven. This, however, is a roller coaster that engenders peace.

For those who are not aware of this, more information on this topic and how to conform you're life to this pattern, read The Little Oratory; A Beginner's Guide to Prayer in the Home and especially the section, A Beautiful Pattern of Prayer.

Pictures: The baptismal font, top, is 11th century, from Magdeburg cathedral. The floor patterns are from the cathedral at Monreale, in Sicily and from the 12th century. The building is the 13th century octagonal baptistry in Cremona, Italy.

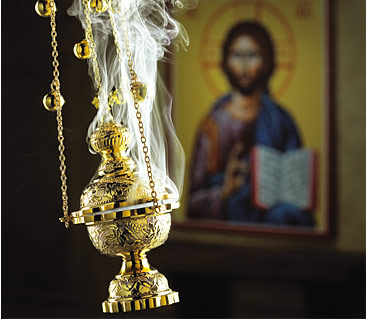

How to Make an Icon Corner

Beauty calls us to itself and then beyond, to the source of all beauty, God. God's creation is beautiful, and God made us to apprehend it so that we might see Him through it. The choice of images for our prayer, therefore, is important. Beautiful sacred imagery not only aids the process of prayer, but what we pray with influences profoundly our taste: praying with beautiful sacred art is the most powerful education in beauty that there is. In the end this is how we shape our culture, especially so when this is rooted in family prayer. The icon corner will help us to do that. I am using icon here in the broadest sense of the term, referring to a sacred image that depicts the likeness of the person portrayed. So one could as easily choose Byzantine, gothic or even baroque styles.

The contemplation of sacred imagery is rooted in man’s nature. This was made clear by the 7th Ecumenical Council, at Nicea. Through the veneration icons, our imagination takes us to the person depicted. The veneration of icons, therefore, is an aid to prayer first and it serves to stimulate and purify the imagination. This is discussed in the writings of Theodore the Studite (759-826AD), who was one of the main theologians who contributed to the resolution of the iconoclastic controversy.

Beauty calls us to itself and then beyond, to the source of all beauty, God. God's creation is beautiful, and God made us to apprehend it so that we might see Him through it. The choice of images for our prayer, therefore, is important. Beautiful sacred imagery not only aids the process of prayer, but what we pray with influences profoundly our taste: praying with beautiful sacred art is the most powerful education in beauty that there is. In the end this is how we shape our culture, especially so when this is rooted in family prayer. The icon corner will help us to do that. I am using icon here in the broadest sense of the term, referring to a sacred image that depicts the likeness of the person portrayed. So one could as easily choose Byzantine, gothic or even baroque styles.

The contemplation of sacred imagery is rooted in man’s nature. This was made clear by the 7th Ecumenical Council, at Nicea. Through the veneration icons, our imagination takes us to the person depicted. The veneration of icons, therefore, is an aid to prayer first and it serves to stimulate and purify the imagination. This is discussed in the writings of Theodore the Studite (759-826AD), who was one of the main theologians who contributed to the resolution of the iconoclastic controversy.

In emphasising the importance of praying with sacred images Theodore said: “Imprint Christ…onto your heart, where he [already] dwells; whether you read a book about him, or behold him in an image, may he inspire your thoughts, as you come to know him twofold through the twofold experience of your senses. Thus you will see with your eyes what you have learned through the words you have heard. He who in this way hears and sees will fill his entire being with the praise of God.” [quoted by Cardinal Schonborn, p232, God’s Human Face, pub. Ignatius.]

It is good, therefore for us to develop the habit of praying with visual imagery and this can start at home. The tradition is to have a corner in which images are placed. This image or icon corner is the place to which we turn, when we pray. When this is done at home it will help bind the family in common prayer.

![]() Accordingly, the Catechism of the Catholic Church recommends that we consider appropriate places for personal prayer: ‘For personal prayer this can be a prayer corner with the sacred scriptures and icons, in order to be there, in secret, before our Father. In a Christian family kind of little oratory fosters prayer in common.’(CCC, 2691)

Accordingly, the Catechism of the Catholic Church recommends that we consider appropriate places for personal prayer: ‘For personal prayer this can be a prayer corner with the sacred scriptures and icons, in order to be there, in secret, before our Father. In a Christian family kind of little oratory fosters prayer in common.’(CCC, 2691)

I would go further and suggest that if the father leads the prayer, acting as head of the domestic church, as Christ is head of the Church, which is His mystical body, it will help to re-establish a true sense of fatherhood and masculinity. It might also, I suggest, encourage also vocations to the priesthood.

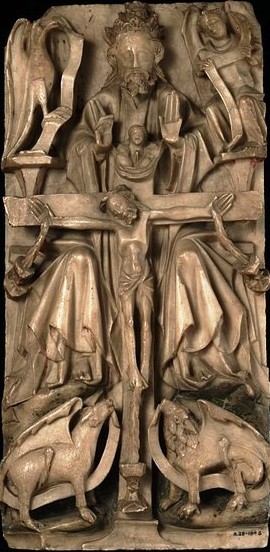

The placement should be so that the person praying is facing east. The sun rises in the east. Our praying towards the east symbolizes our expectation of the coming of the Son, symbolized by the rising sun. This is why churches are traditionally ‘oriented’ towards the orient, the east. To reinforce this symbolism, it is appropriate to light candles at times of prayer. The tradition is to mark this direction with a cross. It is important that the cross is not empty, but that Christ is on it. in the corner there should be representation of both the suffering Christ and Christ in glory.

‘At the core of the icon corner are the images of the Christ suffering on the cross, Christ in glory and the Mother of God. An excellent example of an image of Christ in glory which is in the Western tradition and appropriate to the family is the Sacred Heart (the one from Thomas More College's chapel, in New Hampshire, is shown). From this core imagery, there can be additions that change to reflect the seasons and feast days. This way it becomes a timepiece that reflects the cycles of sacred time. The “instruments” of daily prayer should be available: the Sacred Scriptures, the Psalter, or other prayer books that one might need, a rosary for example.

This harmony of prayer, love and beauty is bound up in the family. And the link between family (the basic building block upon which our society is built) and the culture is similarly profound. Just as beautiful sacred art nourishes the prayer that binds families together in love, to each other and to God; so the families that pray well will naturally seek or even create art (and by extension all aspects of the culture) that is in accord with that prayer. The family is the basis of culture.

Confucius said: ‘If there is harmony in the heart, there will be harmony in the family. If there is harmony in the family, there will be harmony in the nation. If there is harmony in the nation, there will be harmony in the world.’ What Confucius did not know is that the basis of that harmony is prayer modelled on Christ, who is perfect beauty and perfect love. That prayer is the liturgical prayer of the Church.

A 19th century painting of a Russian icon corner

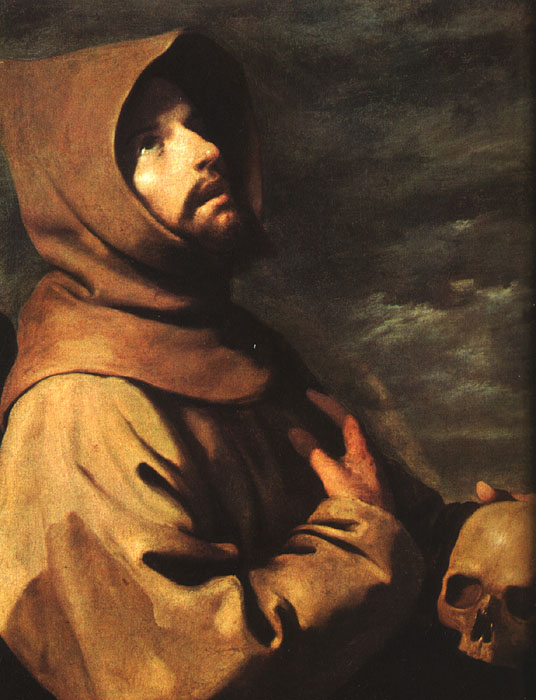

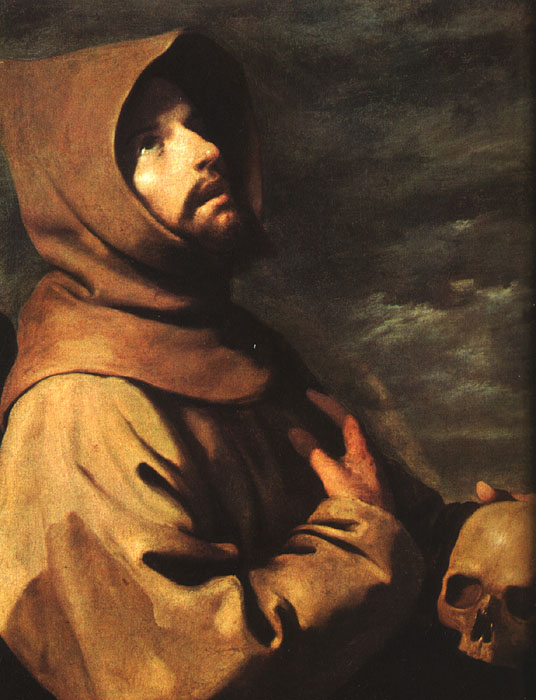

The Dynamic of Prayer with Baroque Sacred Art - Why the Style of the Painting Makes You Pray Well

And how it is connected with the rosary. Have you ever had the experience of walking into an art gallery and being struck by a wonderful painting on the far side of the room. You are so captivated by it that you want to get closer. As you approach it, something strange happens. The image goes out of focus and dissolves into a mass of broad brushstrokes and unity of the image is lost. Then, in order to get a unified picture of the whole you have to recede again. The painting is likely to be an Old Master produced in the style of the 17th-century baroque, perhaps a Velazquez, or a Ribera, or perhaps later artists who retained this stylistic effect, such as John Singer Sargent. I recently made a trip to the art museum at Worcester, Massachusetts and there was a portrait by Sargent there that was about 12ft high and forced us back maybe 35ft so that we could view the whole.

This is a deliberately contrived effect of baroque painting. These paintings are created to have optimum impact at a distance. It is sad that the art gallery is the most likely place for us to find any art, let alone any sacred art that conforms to its principles. The stylistic elements of the baroque relate to its role firstly as a liturgical art form in the Counter-Reformation. The baroque of the 17th century is also the last style historically that Benedict XVI cites as an authentic liturgical tradition - where there is a full integration of theology and form - It should be of no surprise that this has an impact upon prayer.

The best analysis of the stylistic features of the baroque of the 17th century that I have seen is in a book about Velazquez, published in 1906 and written by RAM Stevenson (the brother of Robert Louis). RAM Stevenson trained as a painter in the same studio in Paris as John Singer Sargent. This studio, run by a man called Carolos Duran was unusual in the 19th century in that it did not conform to the sentimental academic art of the time (such as we might have seen in Bougeureau, whose painting is shown above), but sought to mimic the style the great artists of the 17th century, such as Velazquez. In this he says: “A canvas should express a human outlook on the world and so it should represent an area possible to the attention; that is, it should subtend an angle of vision confined to certain natural limits of expansion.[1] ” In other words we need to stand far enough away from the painting so that the eye can take it in as a single impression. Traditionally (following on from Leonardo) this is taken to be a point three times longer than the greatest dimension of the painting. This ratio of 3:1 is in fact an angle of 18°, slightly larger than the natural angle of focused vision of the eye, which is about 15°. When you stand this distance away, the whole painting can be taken in comfortably, without forcing the eye to move backwards and forwards over it to any extent that is uncomfortable.

If the intention is to appear sharp and in focus at a distance of three times the length of the canvas, it must be much painted as much softer and blurred on the canvas itself. In practice this means that when one approaches a canvas, the brush stroke is often broader than one first expected. So that if we do examine a painting close too, it is often hard to discern anything, it almost looks like a collection of random brush strokes. The whole thing only comes together and knits into an image once we retreat again far enough to be able to see it as a unified image. This property makes baroque art particularly suitable for paintings that are intended to have an impact at a distance. The scene jumps out at us.

If the intention is to appear sharp and in focus at a distance of three times the length of the canvas, it must be much painted as much softer and blurred on the canvas itself. In practice this means that when one approaches a canvas, the brush stroke is often broader than one first expected. So that if we do examine a painting close too, it is often hard to discern anything, it almost looks like a collection of random brush strokes. The whole thing only comes together and knits into an image once we retreat again far enough to be able to see it as a unified image. This property makes baroque art particularly suitable for paintings that are intended to have an impact at a distance. The scene jumps out at us.

There is an additional optical device that contributes to this. The composition of the painting is such that the figures are painted in the foreground. Two things: the placement of the horizon; and the relationship between the angle of vision of the perimeter of the canvas and that angle which spans each figure within, affect the sense of whether the image is in the foreground, middle ground or background in relation to the observer. Baroque art tends to portray the key figures in the foreground. When these two effects are combined the effect is powerful.

If we look consider the very famous painting of Christ on the cross by Velazquez, for example. Its appearance at a distance is of a perfectly modeled figure. As we approach we see that much of the detail is painted with a very loose, broad brush. I have picked out the loin cloth and face as detail examples. The artist achieves this effect is achieved by retreating from the canvas, viewing the subject at a distance and then walking forward to paint the canvas from memory. Then after making the brushstroke the artist returns to review the work from the position from which he intends the viewer to see it several feet back. I learnt this technique when I studied portrait painting in Florence. I was on my feet, walking backwards and forwards for two three-hour sessions a day (punctuated by cappuccino breaks, of course). Over the course of an academic year I lost several pounds! I was told, though I haven’t been able to confirm the truth of it, that Velazquez did not feel inclined to do all that walking, so had a set of brushes made that had 10ft handles.

This dynamic between the viewer and the painting is consistent with the idea of baroque art which is to make God and his saints present to us here, in this fallen world. There may be evil and suffering, but God is here for us. Hope in Christ transcends all human suffering. The image says, so to speak, ‘you stay where you are – I am coming to you. I am with you, supporting you in your suffering, here and now’. The stylistic language of light and dark in baroque painting supports this also. The deep cast shadow represents evil and suffering, but it is always contrasted with strong light, representing the Light that ‘overcomes the darkness’.

This dynamic between the viewer and the painting is consistent with the idea of baroque art which is to make God and his saints present to us here, in this fallen world. There may be evil and suffering, but God is here for us. Hope in Christ transcends all human suffering. The image says, so to speak, ‘you stay where you are – I am coming to you. I am with you, supporting you in your suffering, here and now’. The stylistic language of light and dark in baroque painting supports this also. The deep cast shadow represents evil and suffering, but it is always contrasted with strong light, representing the Light that ‘overcomes the darkness’.

This is different to the effect of the two other Catholic liturgical traditions as described by Pope Benedict XVI, the gothic and the iconographic. These place the figures compositionally always in the middle ground or distance, and so they always pull you in towards them. As you approach them they reveal more detail. (See a previous article on written for the New Liturgical Movement on the form of icons for more the reasons for this).

In this respect these traditions are complementary, rather than in opposition to each other. It has since struck me that the mysteries of the rosary describe this complementary dynamic also. They seem to describe an oscillating passage from earth to heaven and back again that helps us understand that God is simultaneously his calling us from Heaven to join him, but He is also with us here and helping to carry us up there, so to speak. If we consider the glorious mysteries, for example: first Christ is resurrected from the dead and then he ascends to heaven. Then He sends the Holy Spirit from heaven to be with us. Then we consider how Our Lady followed him, in her Assumption, and she and all the saints are in glory praying for us to join them. Both dynamics take place at the Mass itself. Christ comes down to us and is really present in Blessed Sacrament. As we participate in the Eucharist, we are raised up to Him supernaturally and then through Him and in the Spirit to the Father.

[1] RAM Stevenson, The Art of Velazquez, p30.

Creativity in Science through Beauty

Liturgical science?

Here is a Way of Beauty replay of an article first published in April 2010. I included this example as part of my class in architecture and traditional proportion recently, to illustrate the fact that modern science does not invalidate the traditional approach to number, rather it reinforces it......

Liturgical science?

Here is a Way of Beauty replay of an article first published in April 2010. I included this example as part of my class in architecture and traditional proportion recently, to illustrate the fact that modern science does not invalidate the traditional approach to number, rather it reinforces it......

In the Canticle of Daniel, chanted on Lauds Sunday Week 1and all feast days in the Divine Office, all of creation is called to give praise to God. The frosts hail and snow, wind and rain and all the other inanimate aspects of creation listed in this canticle do not give praise to God literally, but through their beauty they direct our praise to God. The cosmos is made for us. Through it, we perceive the Creator. In this sense the whole of Creation is ordered liturgically, in that it directs us to God and we give Him thanks, praise and glory. That thanks and praise of man is expressed most perfectly in the liturgy.

Well it seems that we could modify this canticle in accordance with the discoveries of particle physics, perhaps adding the line: ‘Oh you multiplets of hadronic particles, give praise to the Lord. To Him be highest glory and praise forever.’

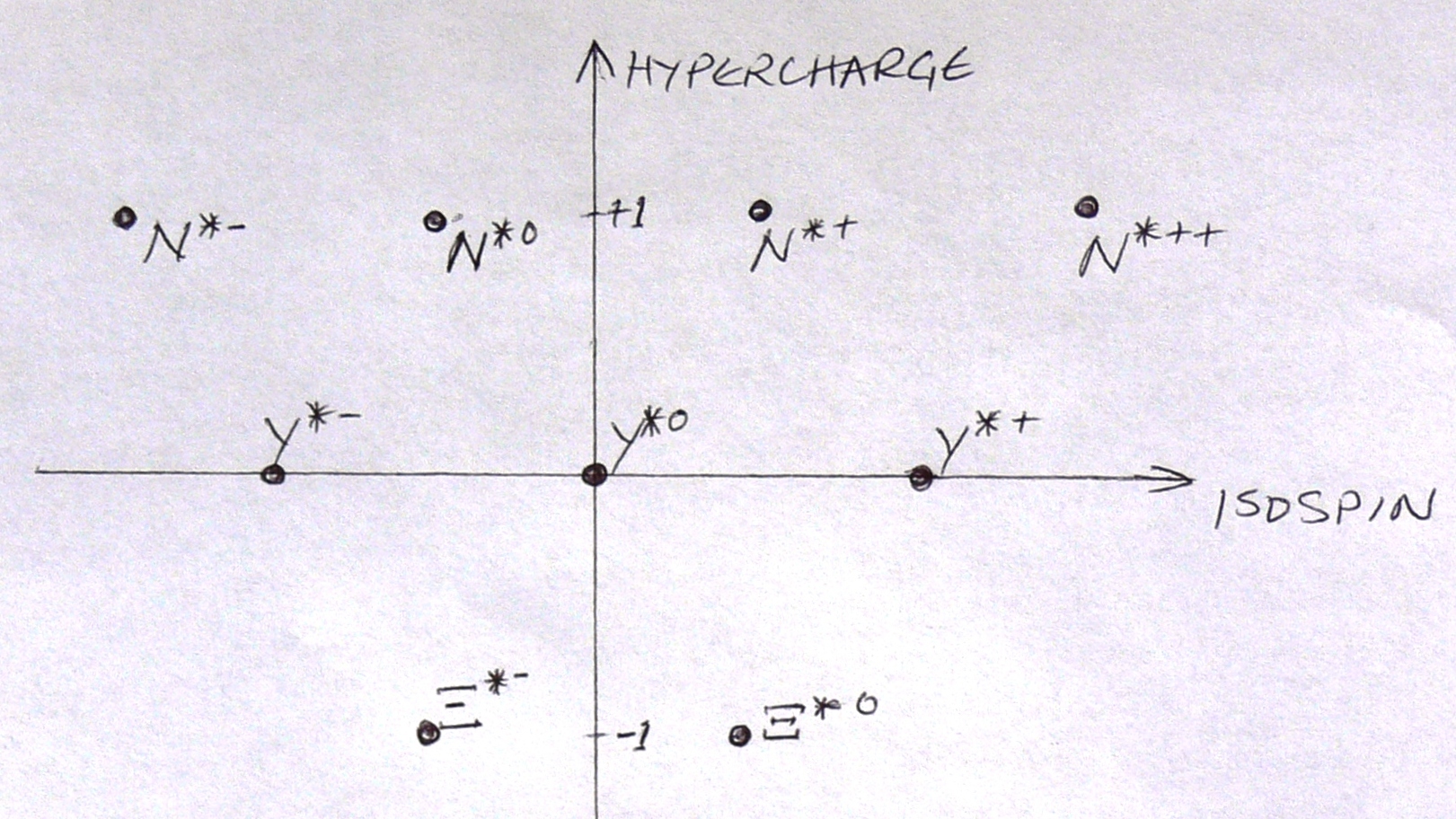

In excellent his book, Modern Physics and Ancient Faith, describing the consistency between the Faith and the discoveries of science, Stephen M Barr describes the scientific investigation of a grouping of sub-atomic particles which he refers to as a ‘multiplet’ of ‘hadronic particles’. He describes how when different properties, called ‘flavours’ of ‘SU(3) symmetry’, of nine of these particles were plotted mathematically, then they produced a patterned arrangement that looked like a triangle with the tip missing.

‘Without knowing anything about SU(3) symmetry, one could guess just from the shape of the multiplet diagram that there should be a tenth kind of particle with properties that allow it to be placed down at the bottom to complete the triangle pattern. This is not just a matter of aesthetics, the SU(3) symmetries require it. It can be shown from the SU(3) that the multiplets can only come in certain sizes….On the basis of SU(3) symmetry Murray Gell-Man predicted in 1962 that there must exist a particle with the right properties to fill out this decuplet. Shortly thereafter, the new particle, called the Ωˉ was indeed discovered.’

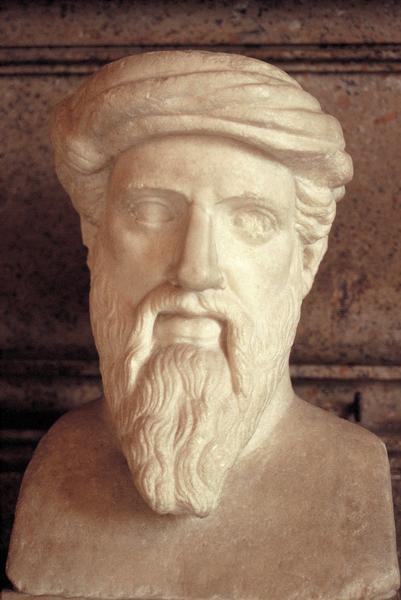

This result would have been of no surprise to anyone who had undergone an education in beauty based upon the quadrivium, - the ‘four ways’ - the higher part of the education of the seven liberal arts of education in the middle-ages[1]. The shape that Murray Gell-Man’s work completed was the triangular arrangement of 10 points known as the tectractys. As described in my previous articles for the New Liturgical Movement, this is the triangular arrangement of the number 10 in a series of 1:2:3:4. 1, 2, 3 and 4 are the first four numbers that symbolize the creation of the cosmos in three dimensions generated from the unity of God; and notes produced by plucking strings of these relative lengths we can construct the three fundamental harmonies of the musical scale. The importance of this in the Christian tradition is indicated by the fact that Raphael’s School of Athens fresco, which is in the Vatican, portrays Pythagoras the Greek philosopher whose ideas were the basis of these ideas of harmony and order. He is portrayed looking at a chalkboard with a diagram of the tectractys and X, the Latin number 10. (Above it on the chalkboard is the diagram which is a geometric construction of the musical harmonies.

The idea that the tectractys might be governing the arrangements of properties of these sub-atomic particles does not prove that it is a correct theorem (although I do find it intriguing!). Nor, even, is knowledge of the tectractys necessary to see the missing dot in this case. As Barr points out, it is obvious once you look at the incomplete graph. But it is obvious only once one works on the assumption that nature is ordered symmetrically. Once Gellman did this, his intuition gave him the missing point. This intuitive leap is the first step in any creative process. We come up first with an idea of what we think it might be, and then test it with reason.

I do not have a deep knowledge of particle physics, but I doubt that the traditional quadrivium contains the full range of symmetries that one is likely to see and would need to use as a research particle physicist. Nevertheless, I would maintain that the traditional education in the quadrivium would enable the research scientist to be more creative in his work. A traditional education in beauty, which is what this is, trains the mind to work in conformity to the divine order, to which, in turn, the natural order conforms. Such a mind is open to inspiration from the Creator, and is more likely to make the necessary intuitive leap when placed with an array of data. The mind that habitually looks to the divine symmetry is more likely to see the natural symmetry.

Physicist A. Zee put it this: ‘Symmetries have played an increasingly central role in our understanding of the physical world. From rotational symmetry physicists went on to formulate ever more abstruse symmetries…fundamental physicists are sustained by the faith that the ultimate design is suffused with symmetries.Contemporary physics would not have been possible without symmetries to guide us…Learning from Einstein, physicists impose symmetry and see that a unified conception of the physical world may be possible. They hear symmetries whispered in their ears. As physics moves further away from everyday experience and closer to the mind of the Ultimate Designer, our minds are trained away from their familiar moorings…The point to appreciate is that contemporary theories, such as grand unification or superstring, have such rich and intricate mathematical structures that physicists must martial the full force of symmetry to construct them. They cannot be dreamed up out of the blue, nor can they be constructed by laboriously fitting one experimental fact after another. These theories are dictated by Symmetry.’[2]

And what has this to do with the liturgy? I quote from my article on the quadrivium, The Way of Beauty, which appeared on the New Liturgical Movement website in September:

‘The traditional quadrivium is essentially the study of pattern, harmony, symmetry and order in nature and mathematics, viewed as a reflection of the Divine Order. When we perceive something that reflects this order, we call it beautiful. For the Christian this is the source, along with Tradition, that provides the model upon which the rhythms and cycles of the liturgy are based. Christian culture, like classical culture before it, was also patterned after this cosmic order; this order which provides the unifying principle that runs through every traditional discipline. Literature, art, music, architecture, philosophy –all of creation and potentially all human activity- are bound together by this common harmony and receive their fullest meaning in the liturgy…When we apprehend beauty we do so intuitively. So an education that improves our ability to apprehend beauty develops also our intuition. All creativity is at source an intuitive process. This means that professionals in any field including business and science would benefit from an education in beauty because it would develop their creativity. Furthermore, the creativity that an education in beauty stimulates will generate not just more ideas, but better ideas. Better because they are more in harmony with the natural order. The recognition of beauty moves us to love what we see. So such an education would tend to develop also, therefore, our capacity to love and leave us more inclined to the serve God and our fellow man. The end result for the individual who follows this path is joy.’

When the person is habitually ordering his life liturgically, he will tap into this creative force, for he will be inspired by the Creator. Meanwhile all those multiplets of hadronic particles in the cosmos will be giving praise to the Lord.

[1] For more details of the quadrivium read the following articles written by me for the New Liturgical Movement website: Cosmic Liturgy and the Mind of God; On Number; Harmony and Proportion; The Way of Beauty at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts

[2] A Zee: Fearful Symmetry, the Search for Beauty in Modern Physics (New York, Macmillan, 1986) p281. Quoted by Stephen M Barr in A Student Guide to Natural Science (Delaware, ISI Books, 1986) p71.

How to Pray With Visual Imagery

It is now more than three and a half years since I started this blog so first of all I would like to thank so many of you for your interest and your comments. I am currently involved in several book projects which will be published in the early part of next year - more information to come. In order to give myself time to write these, I thought I would reduce my postings to one fresh piece per week. However, it also occurred to me that many of you who read this, will not have seen much of what I posted in the first two years. In my mind, these are foundational to my thinking and shed light on much of what I write now, so I thought they would be worth repeating. So for these two reasons I thought I would replay some of these foundational posts. So for the next couple of months, I will alternate old and new. The first replay was first published in April, 2010:

When I first started painting icons I was, of course, interested in knowing as well how they related to prayer. I was referred by others (though not my icon painting teacher) to books that were intended as instruction manuals in visual prayer. I read a couple and perhaps I chose badly, but I struggled with them. One the one hand, they seemed to be suggesting some sort of meditative process in which one spent long quiet periods staring at an icon and experiencing it, so to speak, allowing thoughts and feelings to occur to me. Being by nature an Englishman of the stiff-upper-lip temperament (and happy to be so) I was suspicious of this. I had finally found a traditional method of teaching art that didn’t rely on splashing my emotions on paper, and here I was being told that in the end, the art I was learning to produce was in fact intended to speak to us through a heightened language of emotion. Furthermore, the language used to articulate the methods always seemed to employ what struck me as pseudo-mystical expressions and which, I suspected, were being used to hide the fact that they weren’t really saying very much.

When I first started painting icons I was, of course, interested in knowing as well how they related to prayer. I was referred by others (though not my icon painting teacher) to books that were intended as instruction manuals in visual prayer. I read a couple and perhaps I chose badly, but I struggled with them. One the one hand, they seemed to be suggesting some sort of meditative process in which one spent long quiet periods staring at an icon and experiencing it, so to speak, allowing thoughts and feelings to occur to me. Being by nature an Englishman of the stiff-upper-lip temperament (and happy to be so) I was suspicious of this. I had finally found a traditional method of teaching art that didn’t rely on splashing my emotions on paper, and here I was being told that in the end, the art I was learning to produce was in fact intended to speak to us through a heightened language of emotion. Furthermore, the language used to articulate the methods always seemed to employ what struck me as pseudo-mystical expressions and which, I suspected, were being used to hide the fact that they weren’t really saying very much.

So I started to ask my teacher about this and to observe Eastern Christians praying with icons. What struck me was that prayer for them seemed to be pretty much what prayer was for me. They said prayers that contained the sentiments that they wished to express to God. The difference between what they did and what I did at that time was that they turned and looked at an icon as they prayed. Also, when at home, often happily and without embarrassment they sang their prayers using very simple, easily learnt chant. Before meals, for example, the family would stand up, face an icon of Christ on the wall and sing a prayer of gratitude or even just the Our Father.

As I learnt more about icons through learning to paint them, I realized that every aspect of the style of an icon is worked out to engage us in a dynamic that assists prayer – through its form and content the icon will do the work of directing our thoughts to heaven. In short I don’t need to ‘do’ anything. The icon does the work for me.

The iconographic form is not the only one to do this. The Western Catholic tradition is very rich and has also the Baroque and gothic art forms that are carefully worked out to engage the observer in a dynamic of prayer, although in different ways. If the icon draws our thoughts to heaven, the baroque form is designed in contrast to have an impact at a distance in order to make God present on earth. The gothic figurative art is the art of pilgrimage, or of transition from earth to heaven, and stylistically it sits between the iconographic and baroque. It is the ‘gradual psalm’ of artistic form. Just like the spires of its architecture, it spans the gap between heaven and earth so that we have a sense both of where we going to and where we are coming from. I will discuss how the form of each tradition achieves in the next articles I write.

So the advice I was given was to ditch the books about praying with icons, and learn first to pray. Then as I pray always aim to have visual imagery that I allow to engage my sight and which assists. St Augustine said that those who sing their prayers pray twice. I would add that those who look at visual imagery as well pray three times (and if we use incense four times, and consider posture five). This process of engaging different aspects of the person in addition to the intellect is a move towards the ideal of praying with the whole person. This is what praying from the heart means. The heart is the vector sum of our thoughts and actions. It is our human centre of gravity when both body and soul are considered. It is the single point that, when everything is taken into account, defines what I am doing. It is the heart of us, in the sense of representing the core. This is why it is a symbol of the person. It is a symbol of love also because each of us is made by God to love him and our fellow man. It symbolizes what we ought to be rather than, necessarily, what we are. The modern world has distorted the symbolism of the heart into one of desire and ‘heartfelt’ emotion, precisely because these are the qualities that so many today associate with the essence of humanity.

The liturgy is ultimate form of prayer. By praying with the Church, the mystical body of Christ, we are participating in ‘Christ's own prayer addressed to the Father in the Holy Spirit. In the liturgy, all Christian prayer finds its source and goal.’[1] Therefore, the most important practice of praying with visual imagery is in the context of the liturgy. For example, when we pray to the Father then we look at Christ, for those who have seen Him have seen the Father. The three Catholic figurative traditions in art already mentioned were developed specifically to assist this process.

Just as the liturgy is the ‘source and goal’ of prayer, so liturgical art is, I would argue, the source and goal of all Catholic art. The forms that are united to the liturgy are the basis of Catholic culture. All truly Catholic art will participate in these forms and so even if a landscape in the sitting room, will point us to the liturgical. We cannot become a culture of beauty until we habitually engage in the full human experience of the liturgy. In the context of visual art, this practice will be the source of grace from which artists will be able to produce art that will be the basis of the culture of beauty; the source of grace and from which patrons will know what art to commission; and in turn by which all of us will be able to fulfill our vocation, whatever it may be, by travelling on the via pulchritudinis, the Way of Beauty, recently described by Pope Benedict XVI.

Of course, each individual (depending upon his purse) usually has a limited influence on what art we see in our churches. However, as lay people, we can pray the Liturgy of the Hours and control imagery that we use. The tradition of the prayer corner, in which paintings are placed on a small table or shelf at home as a focus of prayer, is a good one to adopt. We ‘orientate’ our prayer towards this, letting the imagery engage our sight as we do so. We can also sing, use incense and stand, bow, sit or kneel as appropriate while praying. A book I found useful in this regard, which describes traditional practices is called Earthen Vessels (The Practice of Personal Prayer According to the Patristic Tradition) by Gabriel Bunge, OSB

Does this mean that meditation of visual imagery is not appropriate? No it does not. But as with all prayer that is not liturgical, it is should be understood by its relation to the liturgy. So just as lectio divina, for example, is good in that it is ordered to the liturgy because through it our participation in the liturgy is deepened and intensified. So, perhaps, should meditation upon visual imagery should be understood in relation to the use of imagery in the liturgical context. Also, I would say that it is useful, just as with lectio, to avoid the confusion between the Western and Eastern non-Christian ideas of meditation and contemplation are. I was recommended a book recently that helped me greatly in this regard. It is called Praying Scripture for a Change – An Introduction to Lectio Divina by Dr Tim Gray.

[1] CCC, 1073

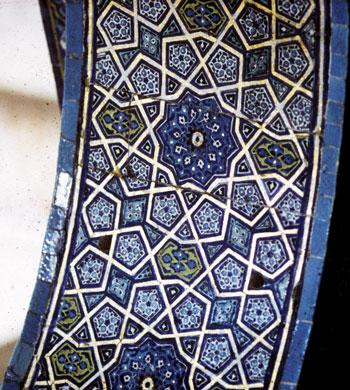

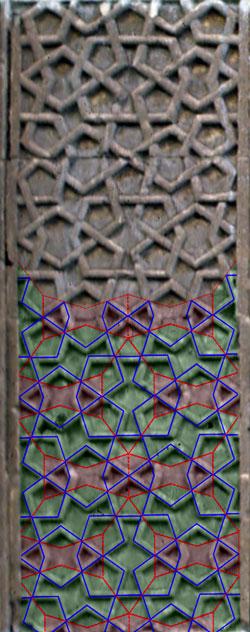

Islamic Tile Patterns Point the Way to Modern Nobel Winning Mathematicians and Chemists

I have written before, here, how the study of sacred geometry and harmony and proportion can point the way to scientists, when describing the discovery of quarks in the early 1960s. Here is another example and the end of the story is this year's Nobel Prize for Chemistry.

Anyone who has studied geometry will know that only threefold and fourfold symettrical patterns are preferred when covering large areas because patterns based on this symmetry will fit together exactly without creating gaps. The Islamic craftsmen of, for example, 13th century Turkey, overcame this difficulty by developing a system of longer range order and using irregular shapes filling the gaps, but creating the sense of a regular order. This way they could create geometric patterns based upon, for example, fivefold symmetry.

I have written before, here, how the study of sacred geometry and harmony and proportion can point the way to scientists, when describing the discovery of quarks in the early 1960s. Here is another example and the end of the story is this year's Nobel Prize for Chemistry.

Anyone who has studied geometry will know that only threefold and fourfold symettrical patterns are preferred when covering large areas because patterns based on this symmetry will fit together exactly without creating gaps. The Islamic craftsmen of, for example, 13th century Turkey, overcame this difficulty by developing a system of longer range order and using irregular shapes filling the gaps, but creating the sense of a regular order. This way they could create geometric patterns based upon, for example, fivefold symmetry.

Move forward to the 1970s and Cambridge mathematician Roger Penfold developed the same idea (independently and unaware of his Islamic predecessors). He called his irregularly shaped insertions 'darts'. About 20 years later the similarity of Penfold's darts to the Islamic tiled patterns was noticed.

These abstract patterns could be extended into three dimensional structures and in the early 1990s microstructure of materials were observed by an Isreali chemist that included, in essence, three-dimensional darts. Here were real materials whose microstructures had been anticipated by the Islamic artists of the 13th century. The discovery of Daniel Schechtman went against the established ideas of what a crystal was his work was not accepted initially. The lab that he was working for asked him to leave. Finally, his work has been recognised now, 20 years later, as ground breaking and he has been awarded the Nobel prize.

The study of traditional proportion and harmony is the study of the natural patterns and rhythms of the cosmos. For the ancients the starting point was those aspects for which there was a consensus of beauty, for example, in enumerating musical harmony. What is so interesting to me is that the patterns seen in a macro scale are observed in atomic and even sub-atomic scale by scientist.

It reinforces the point I made in my first article. That a traditional education in beauty will enhance the creative process. Even in scientific research, ideas are not generated by reason. The process of scientific discovery comes through the observation of nature and then 'seeing' solutions to problems. These solutions just occur as ideas or hunches. The scientist sees the symmetry and order in the situation and can intuit what is missing or what completes the picture, so to speak. Reason is used to test these hypotheses and to confirm or reject them. Of course, this also means that any discipline in which creativity is an asset would benefit from such and education...which is just about every situation in life.

There is another interesting aspect to this tale. It emphasises how the scientist, the mathematician and the artist are all seeking to represent the natural order in different ways, but in their different approaches arriving at the same solution. The scientist is describing mathematically the order that he observes in nature; the mathematician seeks to portray perfect pattern and order in the abstract world of mathematics that conforms to logic and reason; and the geometer seeks to reveal the beauty of the idealised natural order. They are all approaching the same underlying truth and revealing it in different ways.

How an Artist can Seek Creativity and Inspiration

Nearly every artist I meet acknowledges a need for inspiration to guide creativity. The application of every stroke of charcoal or paint must be guided by a picture in the mind of the artist of what he is aiming to create. Sometimes the creation of the work of art involves a carefully thought out, obviously reasoned approach and sometimes it is or more intuitive and spontaneous. However, as long as the process is the realization of an idea and not just a random process without any thought of what the result will be (as with a chimpanzee throwing paint at a canvas) then the artists is employing his intellect and is making decisions about the form he creates. Artists need inspiration in both the formation of the original ideas; and in the decisions about how it will be best achieved.

I have read a number of books claiming to have the secret to creativity and the inspiration of the imagination, a number of them best sellers. Steeped in high emotion and cod psychotherapy, I found them all unconvincing. I have met quite a few people who read them and thought they were wonderful. While it was clear that reading the book made them feel good, none seem to be able to point to visible results in their art (that I could discern at any rate). I was looking for something that actually seemed likely to contribute to my producing better art, rather than something that relieved my anxiety.

Nearly every artist I meet acknowledges a need for inspiration to guide creativity. The application of every stroke of charcoal or paint must be guided by a picture in the mind of the artist of what he is aiming to create. Sometimes the creation of the work of art involves a carefully thought out, obviously reasoned approach and sometimes it is or more intuitive and spontaneous. However, as long as the process is the realization of an idea and not just a random process without any thought of what the result will be (as with a chimpanzee throwing paint at a canvas) then the artists is employing his intellect and is making decisions about the form he creates. Artists need inspiration in both the formation of the original ideas; and in the decisions about how it will be best achieved.

I have read a number of books claiming to have the secret to creativity and the inspiration of the imagination, a number of them best sellers. Steeped in high emotion and cod psychotherapy, I found them all unconvincing. I have met quite a few people who read them and thought they were wonderful. While it was clear that reading the book made them feel good, none seem to be able to point to visible results in their art (that I could discern at any rate). I was looking for something that actually seemed likely to contribute to my producing better art, rather than something that relieved my anxiety.

It seems to me now that the answer is so much simpler than most of these books suggest. This was to use the methods of the Old Masters of the past. All it requires of me is sufficient humility to follow the traditional forms of Western culture. A traditional art education will engender that humility by requiring me to follow the precise directions of the teacher, and by following in the footsteps of the Old Masters by regularly copying their work. (See here for me details on this aspect). No self-expression here! (This incidentally is a lot of the problem, that I could see, with many of the modern methods of trying to generate creativity. Although they might even acknowledge the need for an external source of inspiration, all the popular ones that I read in fact suggested techniques that engendered self-centred self examination that in fact did the opposite - very-loosely based, as far as I could work out on 20th-century psychotherapy methods.)

It seems to me now that the answer is so much simpler than most of these books suggest. This was to use the methods of the Old Masters of the past. All it requires of me is sufficient humility to follow the traditional forms of Western culture. A traditional art education will engender that humility by requiring me to follow the precise directions of the teacher, and by following in the footsteps of the Old Masters by regularly copying their work. (See here for me details on this aspect). No self-expression here! (This incidentally is a lot of the problem, that I could see, with many of the modern methods of trying to generate creativity. Although they might even acknowledge the need for an external source of inspiration, all the popular ones that I read in fact suggested techniques that engendered self-centred self examination that in fact did the opposite - very-loosely based, as far as I could work out on 20th-century psychotherapy methods.)

Regular prayer for inspiration is part of this, and I would say that the traditional prayer of the Church is the best. This comes back, once again to active participation in the liturgy in the fullest sense of the word. Participation in the liturgy, especially when it includes the liturgy of the hours (I have written a series of articles about the Liturgy of the Hours, here) is not only an education in beauty it is the greatest training in creativity and the most powerful prayer of inspiration and guidance.

I have spent much time with Eastern Christians. My initial contact came through learning to paint icons. One of the things that struck me about them was the way they prayed with visual imagery. It seemed to straightforward: they would stand and turn to look the icon in the face, addressing the person depicted directly. Also, they were inclined to sing their prayers in full voice. I might be with a family, for example, and before the meal, they all stood, faced the icon of Christ that was in the dining room and sang an ancient hymn. My reflections on this are in another article called Praying with Visual Imagery.

Upon further reflection, and coming back to this issue of creativity for artists, something that struck me is how unlikely it is that an artist who is not habitually praying with visual imagery is going to be able to produce art that nourishes prayer. If I am habitually making that connection between the prayer and the image, then I will instinctively produce art that nourishes my own prayer. If I am praying well, then that art will be beautiful and will, in turn, nourish the prayers of others. This practice of praying with visual imagery is developing my instincts for what is beautiful. It is also engaging my vision in the prayer, and conforming it to the liturgical practice. This is an act of humility therefore that opens the person as a whole to inspiration and guidance , with a particular focus on that faculty of the visual.

It has been said that historically, that all the great art movements began on the altar. Think of the baroque. It began in the 17th century as the sacred art and architecture of the Catholic counter-Reformation, but this set the style for all art, architecture and music, sacred and profane in both Catholic and Protestant countries.

Therefore the prayer with visual imagery in the context of the liturgy, is a hugely important factor in developing our instincts as to what is beautiful and is the bedrock for the visual aspects of all culture. Just as the liturgy, with the Eucharist at its heart, is the source and summit of human life, so liturgical art is the source of inspiration for and the summit to which all other art participates and directs us to.

I try to do the same when I am participating in the Mass. Once a month we have the Melkite Liturgy at the college and the priest very obviously turns to face the large icons of Our Lady, or of Christ when addressing them in the liturgy. I do my best to take this lesson into my participation in the Roman Rite. Similarly, at the end of Mass on weekdays we say the Angelus, and we all turn and face the statue of Our Lady which is in our little chapel.

I try to do the same when I am participating in the Mass. Once a month we have the Melkite Liturgy at the college and the priest very obviously turns to face the large icons of Our Lady, or of Christ when addressing them in the liturgy. I do my best to take this lesson into my participation in the Roman Rite. Similarly, at the end of Mass on weekdays we say the Angelus, and we all turn and face the statue of Our Lady which is in our little chapel.