In a recent address Pope Benedict XVI praised the work of the 20th century artist Marc Chagal. He described him as a great artist whose work drew inspiration from the Bible, here.

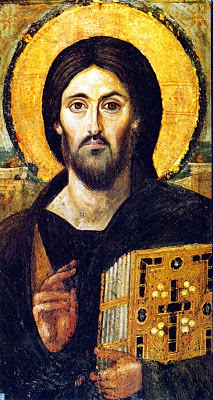

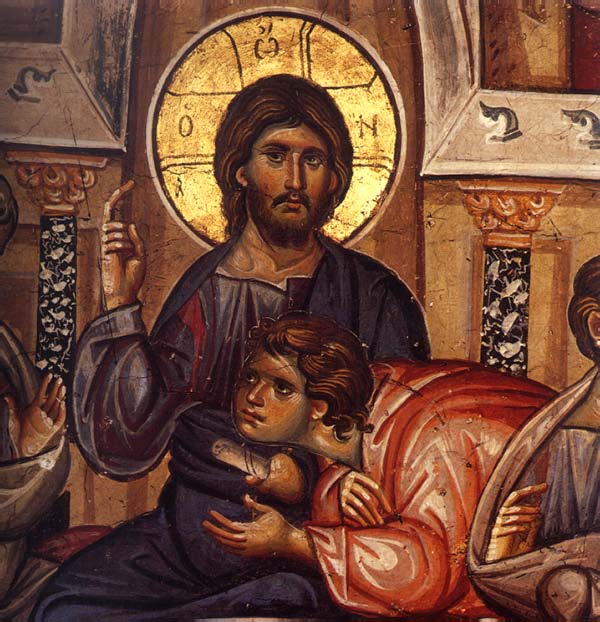

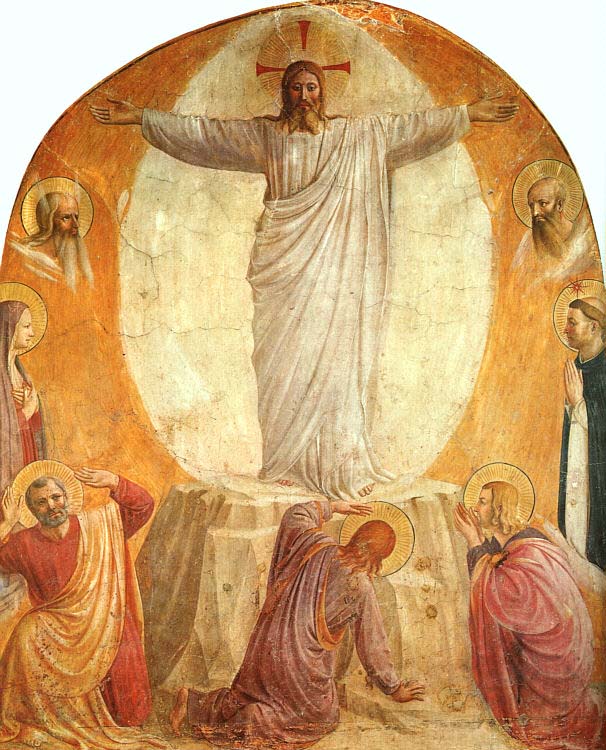

At first sight this might seem surprising. In his book, the Spirit of the Liturgy, Benedict talks of the disconnection between the culture of faith and the wider culture which occurred after the Enlightenment. He cites three artistic traditions as authentically liturgical and all were developed prior to the Enlightenment, namely the iconographic, the gothic and the baroque at its best.

In a recent address Pope Benedict XVI praised the work of the 20th century artist Marc Chagal. He described him as a great artist whose work drew inspiration from the Bible, here.

At first sight this might seem surprising. In his book, the Spirit of the Liturgy, Benedict talks of the disconnection between the culture of faith and the wider culture which occurred after the Enlightenment. He cites three artistic traditions as authentically liturgical and all were developed prior to the Enlightenment, namely the iconographic, the gothic and the baroque at its best.

The bridge to this world of modern art was built by the Romantics, who established the idea that self-expression was the purpose of art. In this context it meant that the task of the artist was limited to the communication his personal views and feelings. Whether or not these views and feelings were based in truth was not important. Success was measured by how accurately or – to use the buzzword of the art world – ‘sincerely’ they were communicated.

If the Romantics built the bridge to modernism, then it was the Impressionists who crossed it and smashed it behind them. Though academically trained themselves, they taught their students to reject tradition (and by this they meant the Western tradition rooted in Christianity) as any basis for guidance. By doing this, they broke any connection with the past that remained. Sadly, they were so successful and influential that everyone listened to them. Up to this point all artists were given the academic training of the Christian tradition that had been developed for the academies of the 17th century. By the 19th century, the training had become detached from its Christian ethos but because the method was still essentially Christian (if misunderstood) the effect was effect on art was visible but subtle (we can distinguish between mid-19th and mid-17th century art for example). After the Impressionists, however, all the academies and ateliers of Europe closed down and artists received neither the skills nor the Christian ethos; the result is the rampant individualism that characterizes the modern era.

Marc Chagall’s work is very much a product of this 20th century spirit of self-expression and individualism.

Marc Chagall’s work is very much a product of this 20th century spirit of self-expression and individualism.

So this raises the question, how can Chagall, whose work conforms in many ways to form of the modern era, be called great by the Holy Father who elsewhere is so clear in stating that the modern mainstream culture is not Christian? Is there a contradiction?

I think not and here’s why. (I should state here that I am basing this purely on what I have read of the Holy Father’s words. I do not claim to have any special inside knowledge of his views.)

Firstly, if individualism is a principle governing the creative process, while it is likely to produce error, it does allow for the possibility of good art. Subjectivity doesn’t necessarily produce ugliness. It is always a possibility that an artist will exercise his freedom wisely and choose to follow what is true and beautiful. I have heard this described as a subjective objectivity…or was it an objective subjectivity (I forget now)? Anyway, whatever we call it, Chagall might be one of these. In order to be certain of this we will have to wait to see whether or not it will transcend its own time – one of the marks of works that contains the timeless principles of beauty. His work has not done this because we are still, essentially, in the modern era.

Secondly, sacred art can be good devotional art without being appropriate for the liturgy. The art that we choose to for our own private prayer is a personal choice based upon what we feel helps our own prayer life. We have to be more careful when selecting art for our churches, allowing for the fact that personal tastes vary. While for my home I would pick whatever appeals to me; for a church I would always choose that art for which there is the greatest consensus over the longest period of time. Accordingly I am much more inclined to put aside personal preference and allow tradition to be the greatest influence in the choices I make. For the liturgy, therefore, I would always choose that art which conforms to the three established liturgical traditions: the baroque, the gothic and the iconographic. I would not put Chagall in a church.

Secondly, sacred art can be good devotional art without being appropriate for the liturgy. The art that we choose to for our own private prayer is a personal choice based upon what we feel helps our own prayer life. We have to be more careful when selecting art for our churches, allowing for the fact that personal tastes vary. While for my home I would pick whatever appeals to me; for a church I would always choose that art for which there is the greatest consensus over the longest period of time. Accordingly I am much more inclined to put aside personal preference and allow tradition to be the greatest influence in the choices I make. For the liturgy, therefore, I would always choose that art which conforms to the three established liturgical traditions: the baroque, the gothic and the iconographic. I would not put Chagall in a church.

This does raise the question as to whether or not any new tradition could ever emerge? None of the established liturgical tradition dropped out of heaven fully formed. They developed over a period of time and in different times. There is no reason to believe that we won’t see more liturgical traditions developing in the future. Could it be that Chagall is a spark that ignites the fire of a new Christian liturgical tradition?

In my opinion, this is possible but very unlikely.

When Caravaggio produced his work at the end of the 16th century it had such an effect on the art of the Rome that nearly all other artists modeled their work on it. However, the basis of this new style was not mysterious. He presented a visual vocabulary that was a fully worked out integration of form and theology. It was the culmination of much work done over a period of time (about 100 years) through a dialogue between artists and the Church’s theologians, philosophers, liturgists. It became the basis for a new tradition because the integration of form and content was articulated and understood, so other artists could learn those principles and apply them in their own work. It was possible to reflect that style, and develop it further, without blindly (so to speak) copying Caravaggio. They copied with understanding.

When Caravaggio produced his work at the end of the 16th century it had such an effect on the art of the Rome that nearly all other artists modeled their work on it. However, the basis of this new style was not mysterious. He presented a visual vocabulary that was a fully worked out integration of form and theology. It was the culmination of much work done over a period of time (about 100 years) through a dialogue between artists and the Church’s theologians, philosophers, liturgists. It became the basis for a new tradition because the integration of form and content was articulated and understood, so other artists could learn those principles and apply them in their own work. It was possible to reflect that style, and develop it further, without blindly (so to speak) copying Caravaggio. They copied with understanding.

Chagall’s work is very much more highly individual in its stylization than that of Caravaggio; and it relies much more on an interpretation of ideas that is directed by intuition rather than reason. Unless we can discern the principles that underlie it and characterize them very clearly, we can copy his work, but it is going to be difficult to do so with sufficient understanding for it to be the basis of a new tradition.

There is another factor that mitigates against Chagal: we live in the age where the tradition is one of anti-tradition. Today’s artists spend most of their time trying to be different be from everyone else. So even if Chagall does represent the beginning of a fourth liturgical tradition and somebody worked out his system of iconography, no tradition derived from it is is going to emerge as long as artists spend most of their time chasing ‘originality’ and consciously trying to differentiate themselves from other work.

Time will tell!

Images from top: White Crucifix; Adam and Eve Expelled from Paradise; Jacob's Dream; Song of Songs; Abraham and the Three Angels; Ruth.