Some Thoughts on How Criticism Might be the Basis of Constructive Dialogue

I wrote this article in response to some comments and criticism of works of art made by readers on another blog after my earlier article on the work of the Spanish artist Kiko; many of my remarks about the tone of the commentators does not apply to thewayofbeauty.org readers, who are always generous in spirit even when being critical. However, I thought that some of the points about the basis of criticism might be of interest to you, so I reproduce it here...

It seems to be an aspect of human nature that criticism flows more easily than praise, and this is never more apparent in the comments at the bottom of blogs! However, some subjects particularly seem to attract the concern of readers and whenever I feature art that draws on the iconographic prototype but deviates from Russian or Greek variants, I always hold my breath. I know it will attract a hail of criticism from people who worry that it does not conform to what they believe to be the standard for all sacred art. Criticism and differing opinions are not bad things in themselves. After all, we are trying to re-establish a culture of beauty in the West and beauty by its very nature it is difficult to pin down precisely. One should expect differing reactions and ideas of what is good. So please, let’s have them. However, I would like to make some points about the nature and tone of some of the criticisms made.

I wrote this article in response to some comments and criticism of works of art made by readers on another blog after my earlier article on the work of the Spanish artist Kiko; many of my remarks about the tone of the commentators does not apply to thewayofbeauty.org readers, who are always generous in spirit even when being critical. However, I thought that some of the points about the basis of criticism might be of interest to you, so I reproduce it here...

It seems to be an aspect of human nature that criticism flows more easily than praise, and this is never more apparent in the comments at the bottom of blogs! However, some subjects particularly seem to attract the concern of readers and whenever I feature art that draws on the iconographic prototype but deviates from Russian or Greek variants, I always hold my breath. I know it will attract a hail of criticism from people who worry that it does not conform to what they believe to be the standard for all sacred art. Criticism and differing opinions are not bad things in themselves. After all, we are trying to re-establish a culture of beauty in the West and beauty by its very nature it is difficult to pin down precisely. One should expect differing reactions and ideas of what is good. So please, let’s have them. However, I would like to make some points about the nature and tone of some of the criticisms made.

First, a request: if you are stating opinions, please do so in the spirit that concedes that others may have other perfectly valid opinions. Like email, blog comments seem to be a forum in which it is difficult not to express things abruptly and so appear rude. It’s not always easy I know, to make sure that what we write has a gentle manner. I would ask us all to try. Aside from discouraging the more timid to respond, for fear of getting more of the same thrown back at them, my concern here is for any contemporary artists whose work I am portraying. Artists must expect criticism of their work, but they should not have to put up with rudeness. Sometimes in embarrassment, I have had felt compelled to contact the artists to them for tone of the comments.

If you can explain why you think as you do, that would be helpful, especially if you don’t like something. If you do not, then what you are giving us is just a subjective opinion. I am not suggesting that we always have to justify our opinions. After all, we’re not always sure ourselves why like or don’t like something. But if they are opinions, let’s make it clear that this is all they are rather than presenting them as indisputable truths.

For example, one work of art was dismissed brusquely ‘pseudo-Byzantine fluff’. Without explanation this amounts to little more than the equivalent of blowing a raspberry at the artist (albeit elegantly articulated). The writer could have stated in addition: how the art in question deviated from the iconographic prototype (which I am assuming is what he was referring to by using the word Byzantine); why he felt that it was wrong to deviate from the iconographic prototype at all (this is not a given); and also, what does he mean by fluff – if he is saying that it is superficial and lacking in meaning? If so what is lacking? Is it possible to characterize why? Otherwise, 'I don't like his work' says it far more accurately; and less rudely.

There are recurring themes on the New Liturgical Movement comments section seem to indicate assumptions about what Catholic art should be that I feel are not correct. I make the following points in respect of these:

First, a request: if you are stating opinions, please do so in the spirit that concedes that others may have other perfectly valid opinions. Like email, blog comments seem to be a forum in which it is difficult not to express things abruptly and so appear rude. It’s not always easy I know, to make sure that what we write has a gentle manner. I would ask us all to try. Aside from discouraging the more timid to respond, for fear of getting more of the same thrown back at them, my concern here is for any contemporary artists whose work I am portraying. Artists must expect criticism of their work, but they should not have to put up with rudeness. Sometimes in embarrassment, I have had felt compelled to contact the artists to them for tone of the comments.

If you can explain why you think as you do, that would be helpful, especially if you don’t like something. If you do not, then what you are giving us is just a subjective opinion. I am not suggesting that we always have to justify our opinions. After all, we’re not always sure ourselves why like or don’t like something. But if they are opinions, let’s make it clear that this is all they are rather than presenting them as indisputable truths.

For example, one work of art was dismissed brusquely ‘pseudo-Byzantine fluff’. Without explanation this amounts to little more than the equivalent of blowing a raspberry at the artist (albeit elegantly articulated). The writer could have stated in addition: how the art in question deviated from the iconographic prototype (which I am assuming is what he was referring to by using the word Byzantine); why he felt that it was wrong to deviate from the iconographic prototype at all (this is not a given); and also, what does he mean by fluff – if he is saying that it is superficial and lacking in meaning? If so what is lacking? Is it possible to characterize why? Otherwise, 'I don't like his work' says it far more accurately; and less rudely.

There are recurring themes on the New Liturgical Movement comments section seem to indicate assumptions about what Catholic art should be that I feel are not correct. I make the following points in respect of these:

1. The iconographic prototype: I am referring here to the art of eschatological man, the form that portrays mankind redeemed and in the heavenly state. The icon is not the only legitimate form of liturgical art and there is no basis for saying that as a form it is superior to any other tradition of liturgical art. And Catholics are not bound by the iconographic form. Therefore, it is simply not a valid criticism in itself to say only that it deviates from the iconographic prototype. If you are going to say this, say how and say why this is problematic. Furthermore, the analysis of the stylistic features of the tradition and the theological explanations for them as we most commonly hear about today didn’t happen until people started to re-establish the form in the Eastern Church in the 20th century. This analysis is still developing. For example, I was taught certain painting methods used in Italy were never used in icons because they contravened the theology that I was told was the foundation of the Eastern method. Subsequently X-ray analysis has demonstrated that this 'Western' method was used in early Eastern icons and might well be the older method of the two. This caused a revision of the statement of allowable methods, and the theology amongst the people who originally taught me.

Catholics especially should be aware that this modern analysis of icongraphic form, though largely very helpful and important, is a work in progress and can sometimes reflect the narrow focus of the predominantly Orthodox who developed it. I have spoken to many people emerge from icon painting classes with the mistaken impression that anything that differs from the form they studied (most commonly Russian and or Greek) is not an icon and not true liturgical art. This is a prejudiced view that doesn’t take into account that there are many other forms, including Western forms, that are consistent with the iconographic prototype; and that the Western artistic tradition is richer, in the sense that it includes the icon but has in addition other authentic liturgical forms that not iconographic.

1. The iconographic prototype: I am referring here to the art of eschatological man, the form that portrays mankind redeemed and in the heavenly state. The icon is not the only legitimate form of liturgical art and there is no basis for saying that as a form it is superior to any other tradition of liturgical art. And Catholics are not bound by the iconographic form. Therefore, it is simply not a valid criticism in itself to say only that it deviates from the iconographic prototype. If you are going to say this, say how and say why this is problematic. Furthermore, the analysis of the stylistic features of the tradition and the theological explanations for them as we most commonly hear about today didn’t happen until people started to re-establish the form in the Eastern Church in the 20th century. This analysis is still developing. For example, I was taught certain painting methods used in Italy were never used in icons because they contravened the theology that I was told was the foundation of the Eastern method. Subsequently X-ray analysis has demonstrated that this 'Western' method was used in early Eastern icons and might well be the older method of the two. This caused a revision of the statement of allowable methods, and the theology amongst the people who originally taught me.

Catholics especially should be aware that this modern analysis of icongraphic form, though largely very helpful and important, is a work in progress and can sometimes reflect the narrow focus of the predominantly Orthodox who developed it. I have spoken to many people emerge from icon painting classes with the mistaken impression that anything that differs from the form they studied (most commonly Russian and or Greek) is not an icon and not true liturgical art. This is a prejudiced view that doesn’t take into account that there are many other forms, including Western forms, that are consistent with the iconographic prototype; and that the Western artistic tradition is richer, in the sense that it includes the icon but has in addition other authentic liturgical forms that not iconographic.

Archeologism: the comments of some seem to stem from an assumption that culture existed in a perfect form at some point in the past and that the work of man over time has caused it to degenerate. The main concern for those who believe this, therefore, is a strict conformity to the past glorious (sometimes arbitrarily assigned) age. Working from tradition, in contrast, is more nuanced. It respects the past and does not seek change without good reason, but always seeks to understand why something was done in a particular way. It accepts that sometimes we must develop and reapply the core principles in response to contemporary challenges or if there is a need to communicate something new. Sometimes this development will be so great that a new tradition is established. The gothic is an example of this. It developed out of the Romanesque, which is an iconographic form, and became a distinct tradition in its own right that presented a different aspect of man.

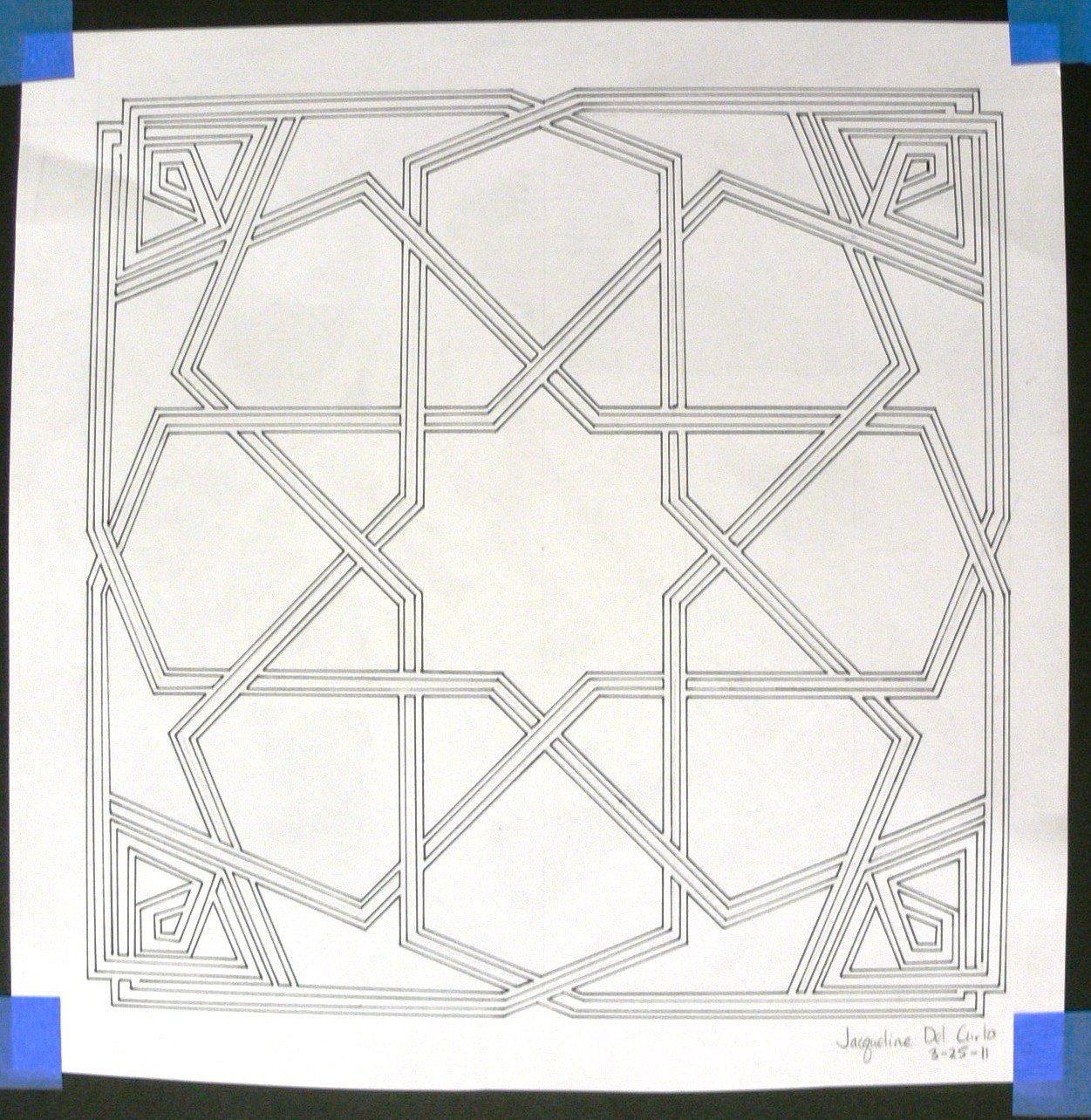

Dealing with imperfection: even if something is partially wrong or in error or even just disliked, it doesn’t mean that we can’t learn something from it. Christian art has always drawn from non-Christian art forms. It has been able to do so in the past because it does have some objective criteria which it can apply in order to discern what is good and what is bad. So for example, you see the first Christian art it developed from the late classical form. Some of the styles and subject matter remained unchanged, some were rejected (for example the nude), and then some features were added that were uniquely Christian. Readers will know that I am very interested in the re-establishment geometric patterned art tradition. Islamic art is likely to be one place that we look to in order to invigorate the Christian tradition today.

As a general principle, given that we are in a process of re-establishing a culture of beauty, I would generally advocate a conservative approach to what goes in our churches at the moment. However, in the context of this forum, I am always interest to look at work by Christian artists that draws on these traditions even if it steps outside the bounds of what would be ideal for the liturgy. Flexibility and adaptability underpinned by good discernment is the source of richness and vigour in Christian culture. To come back to the gothic again. At some point an artist will have added shadow to the painting and although this had not been seen before, some who saw it will have had the confidence to say that although this is new and does not conform to the existing tradition, it is good nevertheless. No doubt along the way there were innovations and experiments that were rejected as a whole, but nonetheless contributed something to what eventually became an acceptable variant.

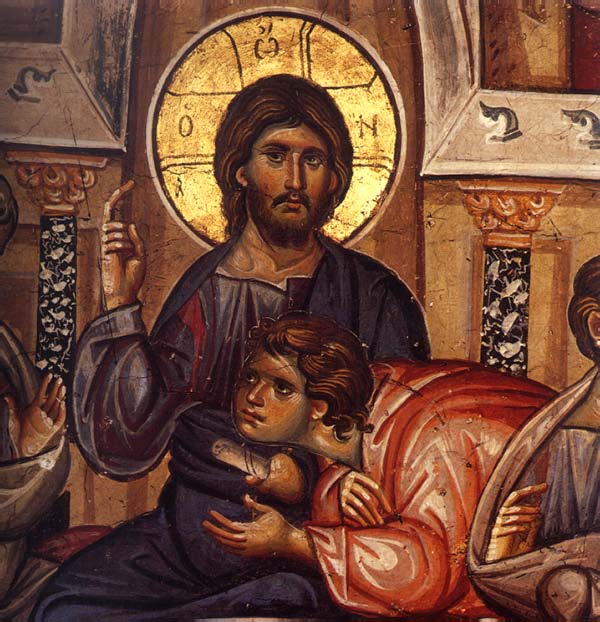

To this illustrate this piece I have given below some that probably fall into the last category. A reader recently brought the work of the Russian artist Viktor Vasnetsov to my attention. He worked in the period around the turn of the last century and died in 1926 and his work is typical of much Russian sacred art of this period. This is a late 19th century naturalistic/iconographic hybrid and is neither baroque nor the style of Russian iconography (it makes me think of an Eastern version of the Pre Raphaelites with its highly coloured, hard-edged forms). I probably wouldn't commission such a work today but I would be a lot happier walking into a church adorned with his art, as shown below, than the vast majority built since the war. There is enough here, I would suggest, for us to benefit from looking at it. When these hybrid styles always look better when painted in fresco, rather than oil, I always feel. Fresco is a medium which tends to look flatter and less sensuous than oil and so naturally diminishes some of the excesses of a naturalistic style.

Archeologism: the comments of some seem to stem from an assumption that culture existed in a perfect form at some point in the past and that the work of man over time has caused it to degenerate. The main concern for those who believe this, therefore, is a strict conformity to the past glorious (sometimes arbitrarily assigned) age. Working from tradition, in contrast, is more nuanced. It respects the past and does not seek change without good reason, but always seeks to understand why something was done in a particular way. It accepts that sometimes we must develop and reapply the core principles in response to contemporary challenges or if there is a need to communicate something new. Sometimes this development will be so great that a new tradition is established. The gothic is an example of this. It developed out of the Romanesque, which is an iconographic form, and became a distinct tradition in its own right that presented a different aspect of man.

Dealing with imperfection: even if something is partially wrong or in error or even just disliked, it doesn’t mean that we can’t learn something from it. Christian art has always drawn from non-Christian art forms. It has been able to do so in the past because it does have some objective criteria which it can apply in order to discern what is good and what is bad. So for example, you see the first Christian art it developed from the late classical form. Some of the styles and subject matter remained unchanged, some were rejected (for example the nude), and then some features were added that were uniquely Christian. Readers will know that I am very interested in the re-establishment geometric patterned art tradition. Islamic art is likely to be one place that we look to in order to invigorate the Christian tradition today.

As a general principle, given that we are in a process of re-establishing a culture of beauty, I would generally advocate a conservative approach to what goes in our churches at the moment. However, in the context of this forum, I am always interest to look at work by Christian artists that draws on these traditions even if it steps outside the bounds of what would be ideal for the liturgy. Flexibility and adaptability underpinned by good discernment is the source of richness and vigour in Christian culture. To come back to the gothic again. At some point an artist will have added shadow to the painting and although this had not been seen before, some who saw it will have had the confidence to say that although this is new and does not conform to the existing tradition, it is good nevertheless. No doubt along the way there were innovations and experiments that were rejected as a whole, but nonetheless contributed something to what eventually became an acceptable variant.

To this illustrate this piece I have given below some that probably fall into the last category. A reader recently brought the work of the Russian artist Viktor Vasnetsov to my attention. He worked in the period around the turn of the last century and died in 1926 and his work is typical of much Russian sacred art of this period. This is a late 19th century naturalistic/iconographic hybrid and is neither baroque nor the style of Russian iconography (it makes me think of an Eastern version of the Pre Raphaelites with its highly coloured, hard-edged forms). I probably wouldn't commission such a work today but I would be a lot happier walking into a church adorned with his art, as shown below, than the vast majority built since the war. There is enough here, I would suggest, for us to benefit from looking at it. When these hybrid styles always look better when painted in fresco, rather than oil, I always feel. Fresco is a medium which tends to look flatter and less sensuous than oil and so naturally diminishes some of the excesses of a naturalistic style.

When depicting Christ or Our Lady one always has to consider their individual characterics

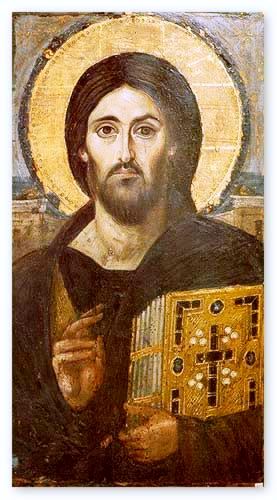

When depicting Christ or Our Lady one always has to consider their individual characterics  There are many depictions of Christ by Western European artists that show him as Western European for the same reasons. When I showed my students the Christ pantocrator, below, many assumed that this was painted in Western Europe too, and were surprised to learn that it was from Mt Sinai in Egypt. I could only offer a speculation as to why his skin tone is paler than one would expect of a working man, a carpenter, in the Middle East, which would surely have been known to the Egytians who saw this image in the 6th century. I suggested that as this was in the iconographic form, the artist would shown the uncreated, heavenly light emanating from the person of Christ. So the lightening of the skin tone is linked, perhaps, along with the other familiar features such as the halo to the depiction of this. As usual I will be interested to see if there any readers who can enlighten us (if you’ll forgive the pun) on this matter.

There are many depictions of Christ by Western European artists that show him as Western European for the same reasons. When I showed my students the Christ pantocrator, below, many assumed that this was painted in Western Europe too, and were surprised to learn that it was from Mt Sinai in Egypt. I could only offer a speculation as to why his skin tone is paler than one would expect of a working man, a carpenter, in the Middle East, which would surely have been known to the Egytians who saw this image in the 6th century. I suggested that as this was in the iconographic form, the artist would shown the uncreated, heavenly light emanating from the person of Christ. So the lightening of the skin tone is linked, perhaps, along with the other familiar features such as the halo to the depiction of this. As usual I will be interested to see if there any readers who can enlighten us (if you’ll forgive the pun) on this matter.

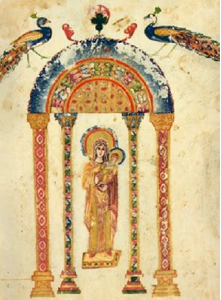

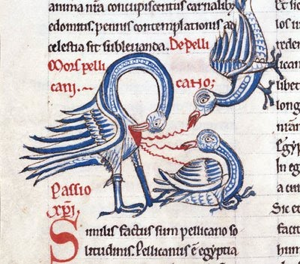

Is there a danger that trying to reestablish traditional Christian symbols in art would sow confusion rather that clarity? Lots of talks and articles about traditional Christian art I see discuss the symbolism of the iconographic content; for example, the meaning of the acacia bush (the immortality of the soul) or the peacock (again, immortality). This is useful if we have a printed (or perhaps for a few of you an original) Old Master in church or a prayer corner as it will enhance our prayer life when contemplating the image. But is this something that we ought to be aiming to reinstate the same symbolism in what we produce today? Should we seek to educate artists to include this symbolic language in their art?

If symbols are meant to communicate and clarify, they should be readily understood by those who see them. This might have been the case when they were introduced – very likely they reflected aspects of the culture at the time – and afterwards when the tradition was still living and so knowledge of this was handed on. But for most it isn’t true now. How many would recognize the characteristics of an acacia bush, never mind what it symbolizes? If you ask someone today who has not been educated in traditional Christian symbolism in art what the peacock means, my guess is that they are more likely to suggest pride, referring to the expression, ‘as proud as peacock’. So the use of the peacock would not clarify, in fact it would do worse than mystify, it might actually mislead. (The reason for the use of the peacock as a symbol of immortality, as I understand it, is the ancient belief that its flesh was incorruptible). So to reestablish this sign language would be a huge task. We would not only have to educate the artists, but also educate everyone for whom the art was intended to read the symbolism. If this is the case, why bother at all, it doesn’t seem to helping very much, and in the end it will always exclude those who are not part of the cognoscenti . This is exactly the opposite of what is desired: for the greater number, it would not draw them into contemplation of the Truth, but push them out.

Is there a danger that trying to reestablish traditional Christian symbols in art would sow confusion rather that clarity? Lots of talks and articles about traditional Christian art I see discuss the symbolism of the iconographic content; for example, the meaning of the acacia bush (the immortality of the soul) or the peacock (again, immortality). This is useful if we have a printed (or perhaps for a few of you an original) Old Master in church or a prayer corner as it will enhance our prayer life when contemplating the image. But is this something that we ought to be aiming to reinstate the same symbolism in what we produce today? Should we seek to educate artists to include this symbolic language in their art?

If symbols are meant to communicate and clarify, they should be readily understood by those who see them. This might have been the case when they were introduced – very likely they reflected aspects of the culture at the time – and afterwards when the tradition was still living and so knowledge of this was handed on. But for most it isn’t true now. How many would recognize the characteristics of an acacia bush, never mind what it symbolizes? If you ask someone today who has not been educated in traditional Christian symbolism in art what the peacock means, my guess is that they are more likely to suggest pride, referring to the expression, ‘as proud as peacock’. So the use of the peacock would not clarify, in fact it would do worse than mystify, it might actually mislead. (The reason for the use of the peacock as a symbol of immortality, as I understand it, is the ancient belief that its flesh was incorruptible). So to reestablish this sign language would be a huge task. We would not only have to educate the artists, but also educate everyone for whom the art was intended to read the symbolism. If this is the case, why bother at all, it doesn’t seem to helping very much, and in the end it will always exclude those who are not part of the cognoscenti . This is exactly the opposite of what is desired: for the greater number, it would not draw them into contemplation of the Truth, but push them out.

An ancient beautiful prayer that leads us to joy, and opens us up to inspiration and creativity; part 1,

An ancient beautiful prayer that leads us to joy, and opens us up to inspiration and creativity; part 1,  If we pray in harmony with rhythms and patterns of the cosmos, especially the cycles of the the sun, the moon and the stars, then the whole person, body and soul, is conforming to the order of heaven. The daily repetitions, the weekly, monthly and season cycles of the liturgy allow us to do just that. In his book, the Spirit of the Liturgy, Pope Benedict XVI calls our apprehension of this order, when we see the beauty of Creation a glimpse into 'the mind of the Creator'. This conformity in prayer opens us up so that we are drawing in the breath of the Spirit, so to speak, as God chooses to exhale. It increases our receptivity to inspiration and God’s consoling grace and leads us more deeply into the mystery of the Mass.

If we pray in harmony with rhythms and patterns of the cosmos, especially the cycles of the the sun, the moon and the stars, then the whole person, body and soul, is conforming to the order of heaven. The daily repetitions, the weekly, monthly and season cycles of the liturgy allow us to do just that. In his book, the Spirit of the Liturgy, Pope Benedict XVI calls our apprehension of this order, when we see the beauty of Creation a glimpse into 'the mind of the Creator'. This conformity in prayer opens us up so that we are drawing in the breath of the Spirit, so to speak, as God chooses to exhale. It increases our receptivity to inspiration and God’s consoling grace and leads us more deeply into the mystery of the Mass.