The iconographic, the Gothic and the Baroque are Complementary Here is a passage taken from the Office of Readings, Saturday, 6th week of Eastertide. It is part of St Augustine’s Commentary of the Gospel of John:

"There are two ways of life that God has commended to the Church. One is through faith, the other is through vision. One is in pilgrimage through a foreign land, the other is in our eternal home; one in labour, the other in repose; one in a journey to our homeland, the other in that land itself; one in action, the other in the fruits of contemplation.

The iconographic, the Gothic and the Baroque are Complementary Here is a passage taken from the Office of Readings, Saturday, 6th week of Eastertide. It is part of St Augustine’s Commentary of the Gospel of John:

"There are two ways of life that God has commended to the Church. One is through faith, the other is through vision. One is in pilgrimage through a foreign land, the other is in our eternal home; one in labour, the other in repose; one in a journey to our homeland, the other in that land itself; one in action, the other in the fruits of contemplation.

The first life, the life of action, is personified by the Apostle Peter; the contemplative life, by John. The first life is passed here on earth until the end of time, when it reaches its completion; the second is not fulfilled until the end of the world, but in the world to come it lasts for ever….”

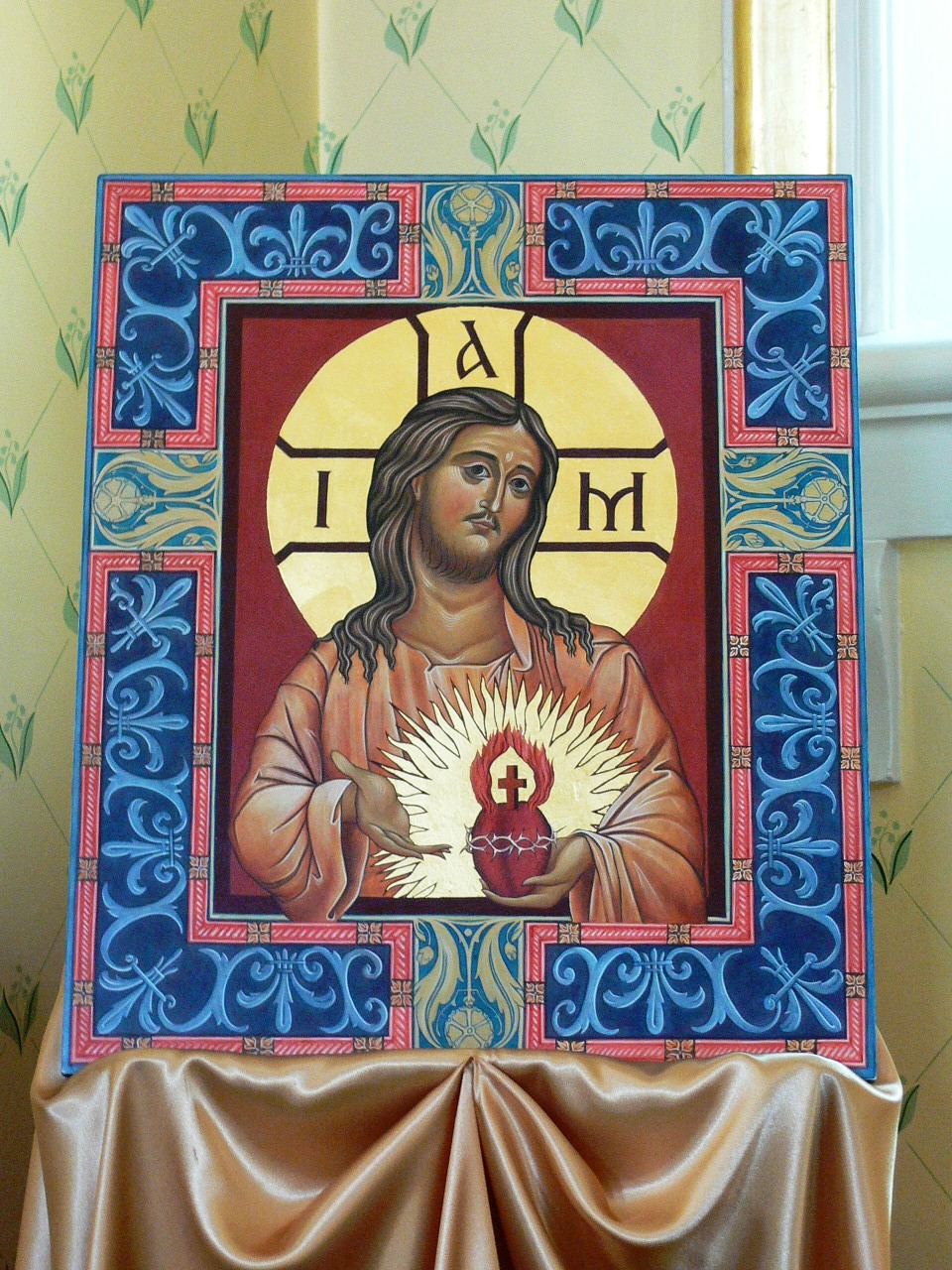

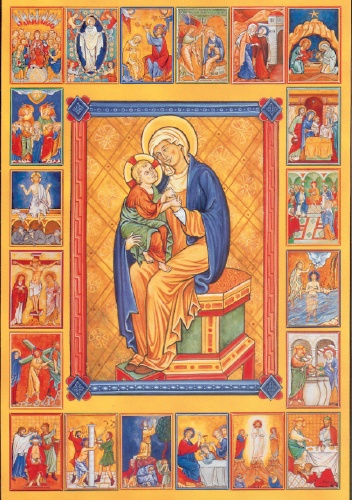

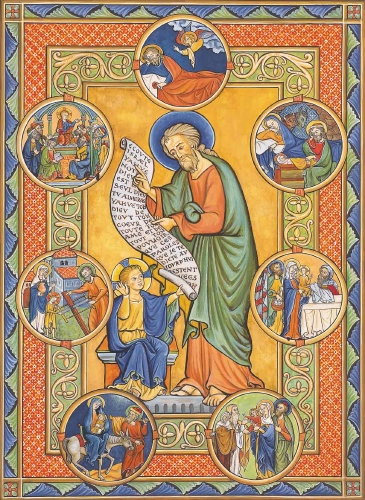

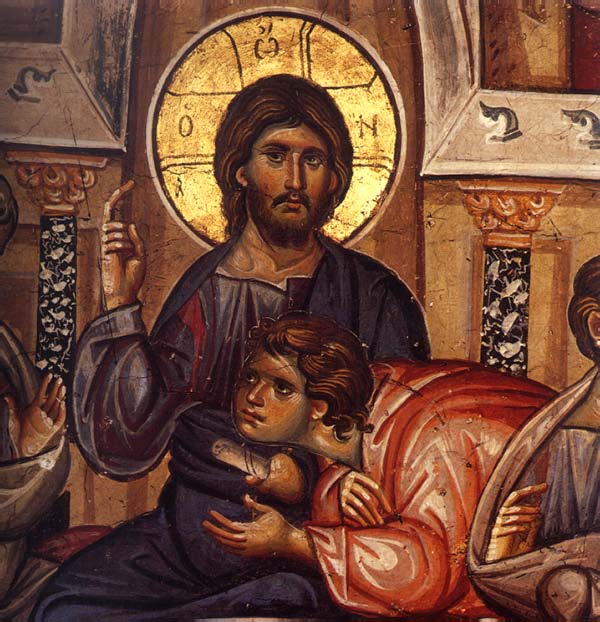

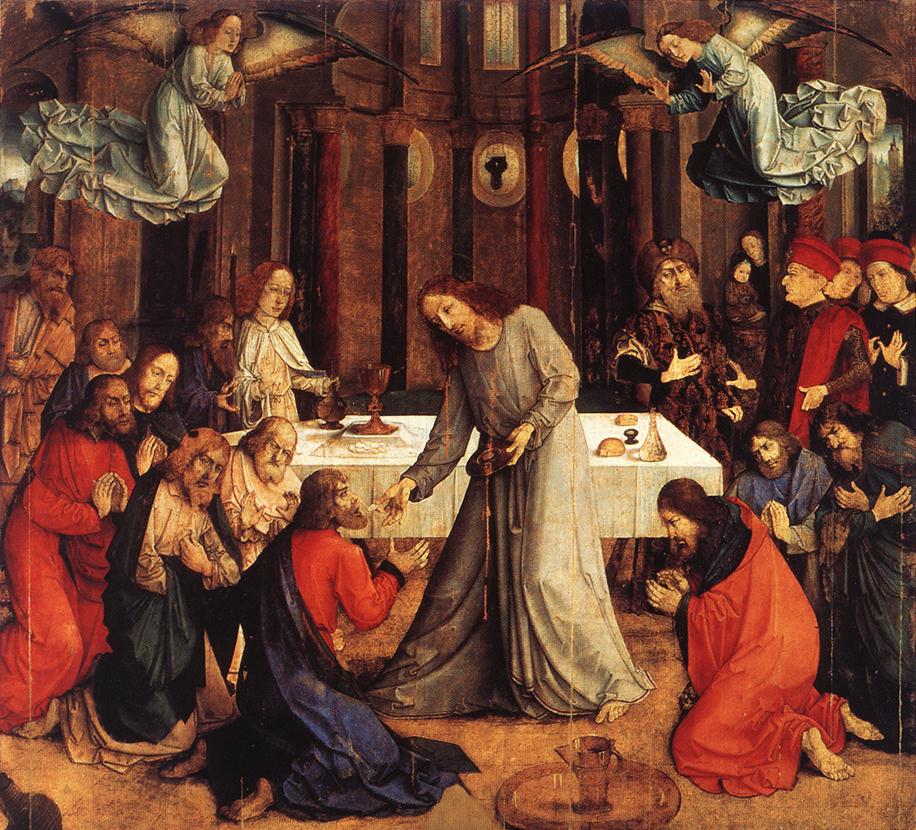

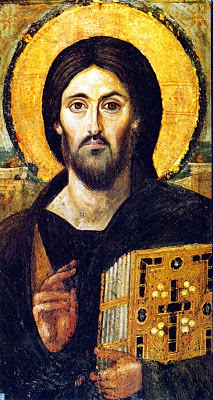

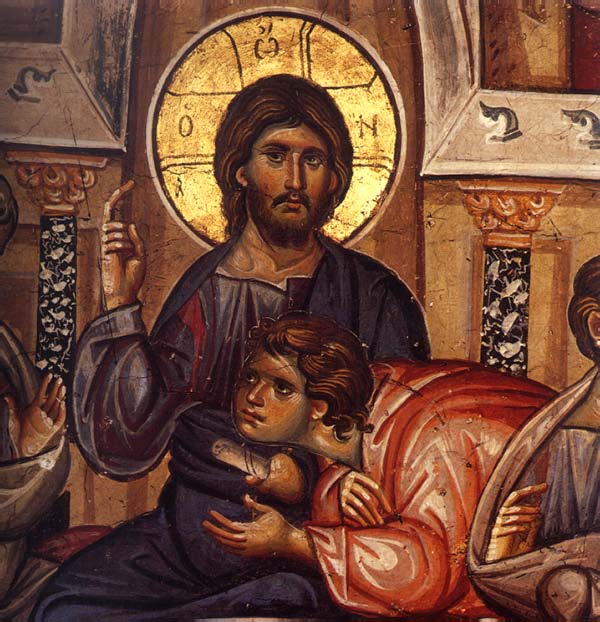

This passage seems to me to describe very well why the Church has different liturgical artistic traditions. The form of the iconographic tradition is governed by the theology of the ‘world to come that lasts forever’ symbolized by St John.

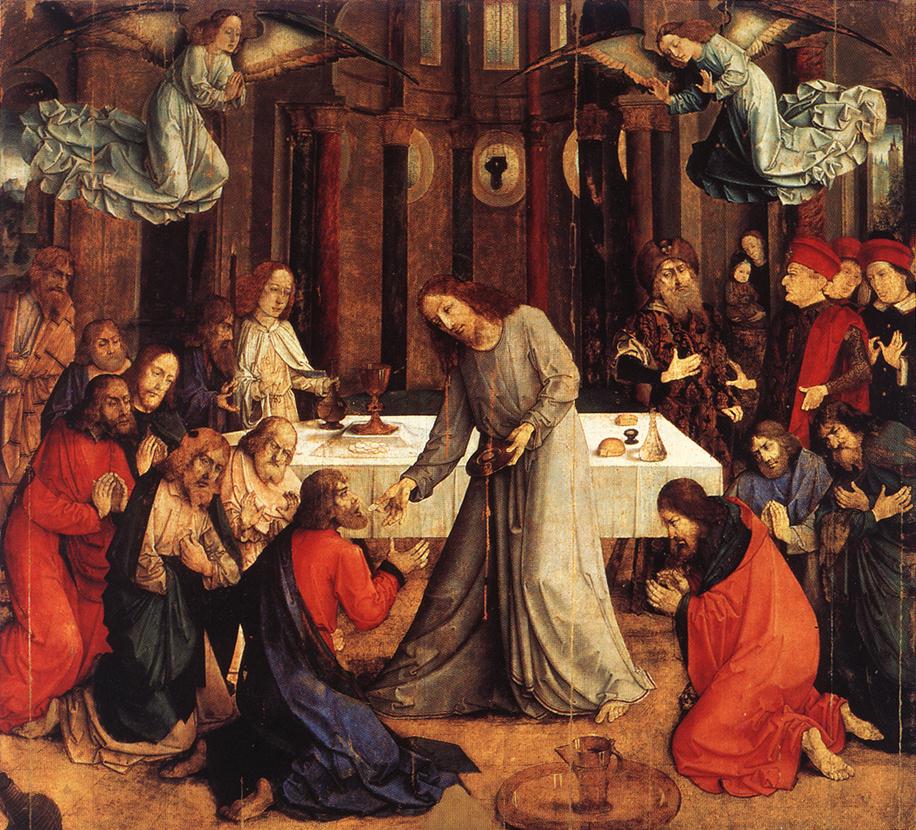

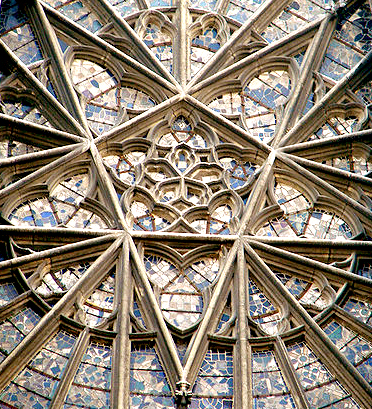

Gothic is art of the ‘pilgrimage through a foreign land’, as Augustine puts it. Stylistically the Gothic is a naturalized iconography. I have written about this here. However, the fusion is not arbitrary. This is a naturalization that is integrated with the theology of pilgrimage that Augustine describes. In this regard it should not be confused with the degenerate forms of iconography that dominated the Eastern Church from the period of the 18th century. (It was not until the 20th century, with figures such as Ouspensky, Gregory Kroug and Fotis Kontoglou that the iconographic prototype was re-established in the main churches of the East.)

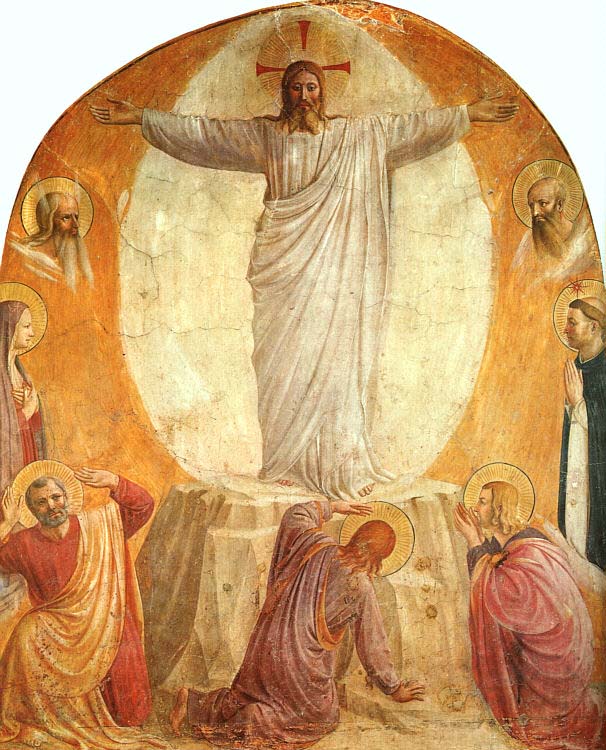

Historically, the Gothic can be seen as something that develops gradually from the Romanesque (a Western variant of the iconographic form). It is almost as if the art form gradually appears from heaven, descending down to earth to join the pilgrims. Duccio, for example, who lived in the late 13th and early 14th centuries has a style that is very closely related to the iconographic. Fra Angelico, in the 15th century, uses both the iconographic visual vocabulary as well as naturalistic ones (such as perspective and shadow) in a theologically coherent way.

Historically, the Gothic can be seen as something that develops gradually from the Romanesque (a Western variant of the iconographic form). It is almost as if the art form gradually appears from heaven, descending down to earth to join the pilgrims. Duccio, for example, who lived in the late 13th and early 14th centuries has a style that is very closely related to the iconographic. Fra Angelico, in the 15th century, uses both the iconographic visual vocabulary as well as naturalistic ones (such as perspective and shadow) in a theologically coherent way.

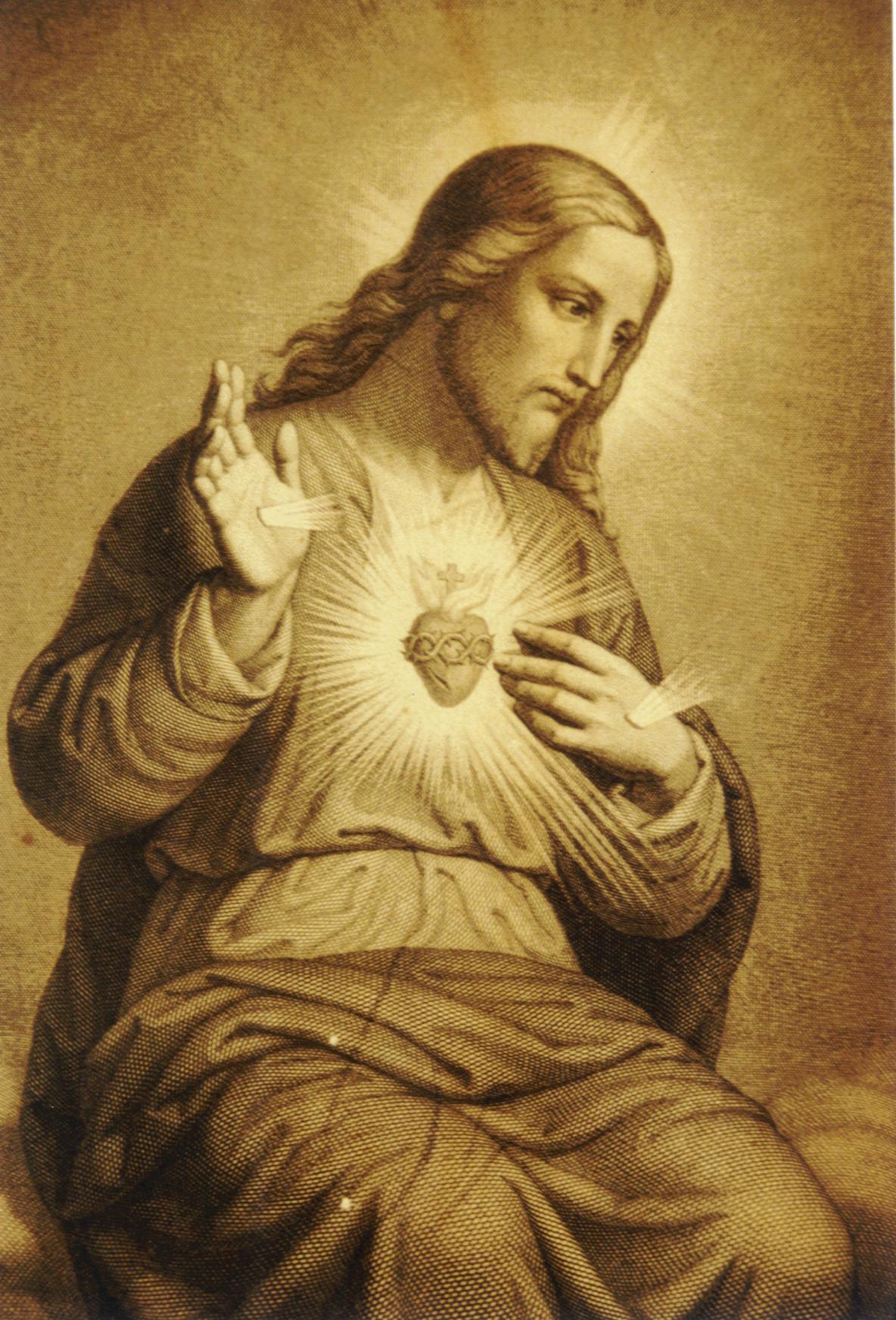

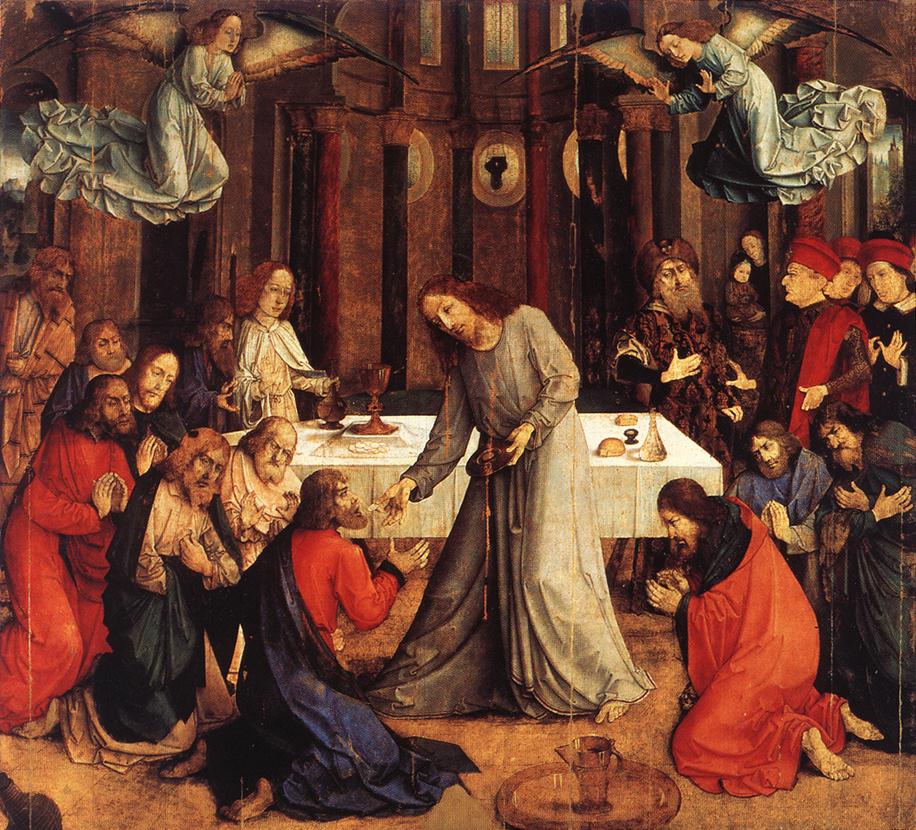

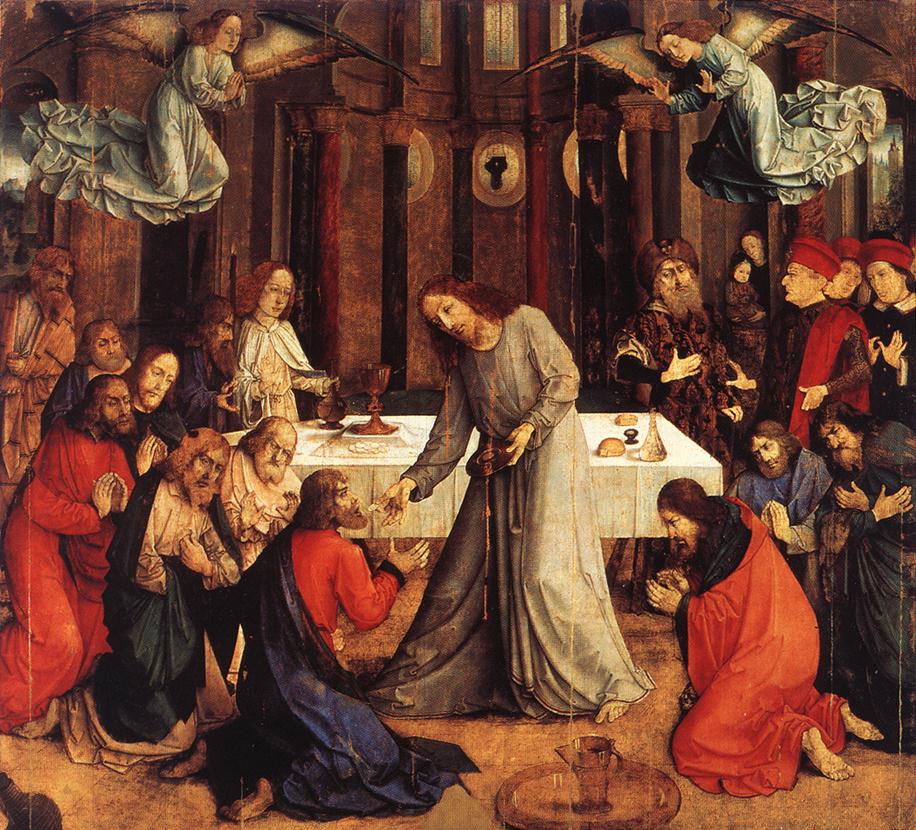

Where does the third authentic liturgical tradition of the Church, the Baroque, sit with these? It was during the Baroque of the 17th century that the integration of theology and form in the most naturalistic of these styles occurred. The controlled variation in colour and focus (described in more detail here) were given theological meaning: we live in a fallen world, with evil and suffering present, but there is hope because God is present – in Baroque art contrast of light and shadow is always painted so to communicate the idea that the Light overcomes the darkness.

Although we cannot reach heaven fully in this life, supernaturally we partially and temporarily step into it through the liturgy and the sacramental life. This is a transforming process that by degrees takes us towards that heavenly state.

In this context, the Baroque is the ground zero, the starting point of our pilgrimage, and the gothic describes the partial and gradual ascent to that heavenly state in this life, before reaching the final repose. The Baroque and the Gothic together represent that aspect of our life in faith symbolized by St Peter in the picture that Augustine paints.

Therefore, these three styles are not in opposition to each other but are complementary. In the light of this I hope to see all three traditions. As each tradition develops, if it bears the mark of a genuinely living tradition, it will be consistent with the timeless principles that define it will, without deviating from the core defining principles, to reflect the time and place that it comes from. Those aspects that are subject to change will be the common ground for each of these traditions. It is possible to envisage a church containing all three traditions that are distinct, yet because they bear the mark of their time, yet containing aspects of form that are common and through this participate in a unified artistic vision.

In regard to the idea that both the Johannine and Petrine aspects of Christian life should be communicated, I leave the last word to St Augustine. Here is the closing passage from the same reading:

In regard to the idea that both the Johannine and Petrine aspects of Christian life should be communicated, I leave the last word to St Augustine. Here is the closing passage from the same reading:

“We should not separate these great apostles. They were both part of the present life symbolized by Peter and they were both part of the future life symbolized by John. Considered as symbols, Peter followed Christ and John remained; but in their living faith both endured the evils of the present life and both looked forward to the future blessings of the coming life of joy.

It is not they alone that do this but the whole of the holy Church, the bride of Christ, who needs to be rescued from the trials of the present and to be brought to safety in the joys of the future. Individually, Peter and John represent these two lives, the present and the future; but both journeyed in faith through this temporal life and both will enjoy the second life by vision, eternally.

All the faithful form an integral part of the body of Christ, and therefore, so that they may be steered through the perilous seas of this present life, Peter, first among the Apostles, has received the keys of the kingdom of heaven, to bind and loose from sin. And also for the sake of the faithful, so that they may keep the still and secret heart of his mode of life, John the evangelist rested on Christ’s breast.

It is not Peter alone who binds and looses sins, but the whole Church. It is not John alone who has drunk at the fountain of the Lord’s breast and pours forth what he had drunk in his teaching of the Word being God in the beginning, God with God, of the Trinity and Unity of God — of all those things which we shall see face to face in his kingdom but now, before the Lord comes, we see only in images and reflections — not John alone, for the Lord himself spreads John’s gospel throughout the world, giving everyone to drink as much as he is capable of absorbing.”

Images from top: Baroque - St Peter being Freed by an Angel (Guercino); iconographic - St John with Christ at the last supper; Gothic - St Peter preaching (Fra Angelico)

Here is a second in a series about late gothic sculpture. This one is written by Dr Christopher Blum and appears in Crisis Magazine (http://www.crisismagazine.com). You can find the article itself here.

One of the questions that I always think about as an artist when I see work that I enjoy is how could we train artists today to work in a similar way today. How does an artist learn to make this style his natural modus operandus. Dr Blum is a historian and his interest is as much on the spirit of the times as the technical skill of the artist. He describes the training and working environment that Riemenschnieder experienced, and focussed particularly on his membership of his town's Guild of St Luke. When guilds are mentioned nowadays there tend to be two reactions. For some it conjures up images of a culturally rich past that we hardly dare dream of emulating today. For others, they are professional organisations that flourished by imposing restrictive trade practices, rather like strident medieval trade union. For my own part, I prefer to put aside the possible negative aspects of the economic organisation of the guilds, and focus on how these associations preserved the attitude of tradition by preserving skills and creating structured environment to train apprentices and which directed their activities activities to the common good. Here is an article that has some thoughts about how the guilds might be a model for the teaching of practical skills today. As a general principle, when considering any aspect of the culture, we should always aim, I feel, to adopt the good and reject the bad.

Here is a second in a series about late gothic sculpture. This one is written by Dr Christopher Blum and appears in Crisis Magazine (http://www.crisismagazine.com). You can find the article itself here.

One of the questions that I always think about as an artist when I see work that I enjoy is how could we train artists today to work in a similar way today. How does an artist learn to make this style his natural modus operandus. Dr Blum is a historian and his interest is as much on the spirit of the times as the technical skill of the artist. He describes the training and working environment that Riemenschnieder experienced, and focussed particularly on his membership of his town's Guild of St Luke. When guilds are mentioned nowadays there tend to be two reactions. For some it conjures up images of a culturally rich past that we hardly dare dream of emulating today. For others, they are professional organisations that flourished by imposing restrictive trade practices, rather like strident medieval trade union. For my own part, I prefer to put aside the possible negative aspects of the economic organisation of the guilds, and focus on how these associations preserved the attitude of tradition by preserving skills and creating structured environment to train apprentices and which directed their activities activities to the common good. Here is an article that has some thoughts about how the guilds might be a model for the teaching of practical skills today. As a general principle, when considering any aspect of the culture, we should always aim, I feel, to adopt the good and reject the bad.

Interestingly, this ratio (5:3) appears also in the description of the construction of the Noah’s ark. St Augustine directly links the dimensions of Noah’s ark to the perfect proportions of a man, exemplified he says, in Christ. This echoes the classical proportions of the perfect man as described by the Roman Vitruvius in his textbook for architects. Furthermore, Boethius, in his book De Arithmetica, lists a series of 10 perfect proportions that he says came from Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle and ‘later thinkers’. The final proportion of the series, called the Fourth of Four contains right at the beginning this ratio. (The references for these can be found in an article Harmonious Proportion in the Christian Tradition, here.)

Interestingly, this ratio (5:3) appears also in the description of the construction of the Noah’s ark. St Augustine directly links the dimensions of Noah’s ark to the perfect proportions of a man, exemplified he says, in Christ. This echoes the classical proportions of the perfect man as described by the Roman Vitruvius in his textbook for architects. Furthermore, Boethius, in his book De Arithmetica, lists a series of 10 perfect proportions that he says came from Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle and ‘later thinkers’. The final proportion of the series, called the Fourth of Four contains right at the beginning this ratio. (The references for these can be found in an article Harmonious Proportion in the Christian Tradition, here.)

The tradition of the Eastern Church

The tradition of the Eastern Church